Father's hunt for answers after son's suicide leads military to modify training and weapons

This is an updated version of a story first published on March 23, 2025. The original video can be viewed here.

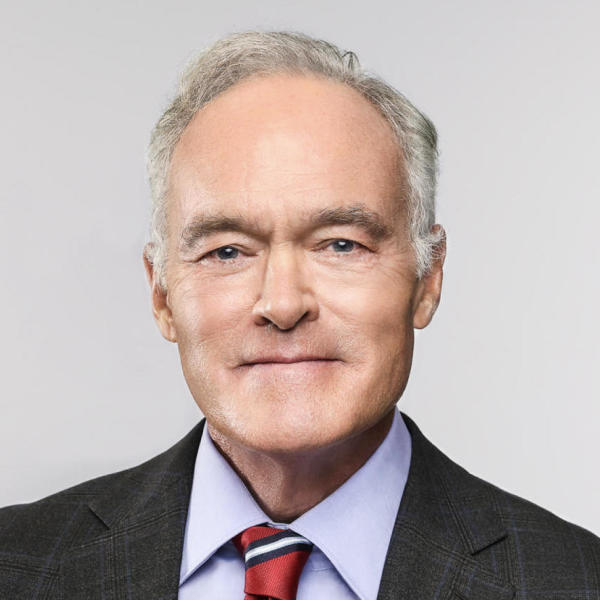

Frank Larkin's service to America is extraordinary—a former Navy SEAL whose government career included the Secret Service, the Pentagon and the U.S. Senate. But Larkin's greatest contribution is happening now, in retirement, after his son, Ryan, a decorated Navy SEAL himself, took his own life. Ryan's death was put down to mental illness—case closed. But as we first told you earlier this year, Frank Larkin didn't buy it. He suspected his son's military service resulted in an invisible brain injury—a kind of wound unknown to science. If Larkin was right, it might explain many military suicides. And so began Larkin's war which would send a shockwave through the Pentagon. It began in April 2017, when Larkin and his wife opened the door to a silent home.

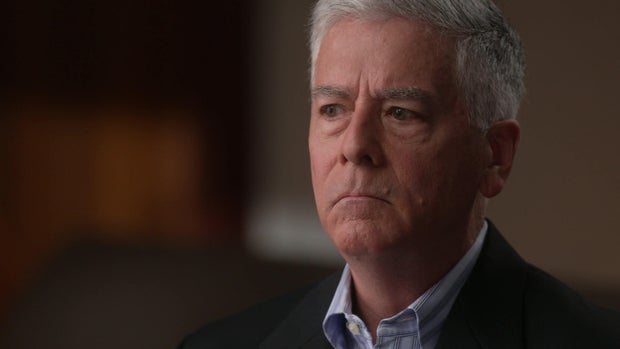

Frank Larkin: I went in the house. We started callin' his name, didn't hear any response. And so, I went into the basement and-- I-- I found him. He-- he had taken his life-- sometime-- during the night. He-- he was dressed in his SEAL Team Seven T-shirt, had a pair of red, white and blue board shorts on. And had illuminated a shadow box next to him that had his, all his medals, ribbons, and other key insignia. It was a shadowbox that I had made for him the previous holiday to just capture, you know, how proud I was of him and what he had done as a symbol of his service to the nation. And then he had also burned a hard drive in the fireplace with all his deployment photos that he had had from, you know, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Africa. I, you know, I-- I've spent over 40 years of my life rescuin' other people. And in the end, I couldn't rescue my own son.

His son, Ryan, was 29. For him the military was destiny. Ryan had been 13 years old in September 2001 when his dad was assigned to the New York Secret Service office across the street from the World Trade Center.

Frank Larkin: He was motivated by 9/11. I had been on the ground on 9/11 in New York City, had gotten caught in all that turmoil. And he had witnessed that from a hillside-- West of the city-- a town that we lived in in New Jersey. And, you know, it emotionally impacted him. I didn't realize how much.

So much, that Ryan joined the Navy out of high school and rose to elite Special Operations—a SEAL—or as Navy slang has it, a "frogman." This is Ryan on one of four combat tours: two in Iraq, two in Afghanistan. One stretch lasted about a year.

Scott Pelley: When did you notice that Ryan was not the Ryan that you knew?

Frank Larkin: It was coming off that year-long deployment. He became short fused. You know, he stopped laughing, which was a key sign. You know, he became very stoic in his facial expression. I would almost characterize it as putting a mask on where at times he would get into this--you know, mode where he was almost looking right through you.

Ryan had returned from the wars to become an instructor in training like this—but his mood only darkened.

Navy doctors scanned Ryan's brain but saw no physical injury. He was treated for depression, alcoholism-- in and out of the hospital.

Frank Larkin: But at no point had they ever settled on a clinical diagnosis as to what was wrong with him. And it just-- it just tore him apart. He said to me, "Dad, I don't feel like I'm in my own body."

Scott Pelley: In August 2016, Ryan wrote the Navy, and he said quote, "I need help. I just want to feel normal again and live a purposeful life. I loved being a SEAL." What is he asking for?

Frank Larkin: He's asking for help. I will say that there are some very good people that were trying to do the right thing for the right reason but maybe all the wrong way, because they just didn't know what they didn't know. While others couldn't be bothered with, you know, a broken frogman, you know. "Let's get rid of it let's get rid of the problem."

In 2016 Ryan was discharged, honorably. He was released from a Navy medical center with an illness no one could correctly diagnose.

Frank Larkin: And he said, "If anything ever happens to me, I want you to donate, you know, my body, my brain for traumatic brain injury research And, of course, as a father, I'm saying, "Hey, look. I'm here for ya. We're-- we're gonna get through this. We're gonna figure this out." I said, you-- you-- you know, "please tell me you're not thinking about hurtin' yourself." You know, "No, Dad. I-- I never will go that way. I'm tellin' ya, I'll never go that way." And-- about a month later, that's exactly what happened.

Frank Larkin's four decades of service prepared him for what came next. A Navy SEAL in the 70s, he spent 20 years in the Secret Service, then led a Pentagon project to defeat roadside bombs in Iraq and Afghanistan. Finally, he became sergeant-at-arms for the U.S. Senate-- in charge of security. Larkin knew people, knew the military, and the ways of Washington.

Frank Larkin: And that put me on this path that I'm on right now, to try to effect change so that we have no more Ryans.

Scott Pelley: A war of your own?

Frank Larkin: That's right. And failure's not an option.

Larkin donated his son's brain to Dr. Daniel Perl at the Uniformed Services University, the military medical school. We met Dr. Perl in 2017 while reporting on how autopsies discovered microscopic scars in the brains of veterans who had taken their own lives. Depression overwhelmed them months or years after the enormous blast of a roadside bomb.

Dr. Daniel Perl (in 2017): And with the explosion comes the formation of something called the blast wave. And it is sufficiently powerful to pass through the skull and through the brain.

Dr. Perl found scarring in Ryan Larkin's brain. But there was one big difference. Larkin had not been hit by a roadside bomb. Most of what he endured was low-level, repeated, shocks from his own weapons. For example, this large caliber rifle notorious for leaving gunners dizzy.

But, even more, there was his job as a trainer. Students came and went but Ryan supervised every blast, every raid, every day.

Frank Larkin: Ryan died from his combat injuries from his service to this nation. He just didn't die right way.

'Injuries' from routine weapons and tactics. Frank Larkin took the evidence to old friends, now in command of Special Operations.

Frank Larkin: They, to their credit, aggressively started to peel the onion on this, and started saying, there's something going on here. We've gotta understand this.

In 2019, Special Operations launched a preliminary study to look for brain injuries from cumulative, low-level blasts. At Frank Larkin's urging, Vice Admiral Tim Szymanski found $4 million and 30 active-duty volunteers who were suffering symptoms.

Dr. Brian Edlow: The symptoms were broad, and they encompassed cognitive symptoms like difficulty with memory and attention, physical symptoms like dizziness and headaches, as well as psychological symptoms, like depression and disinhibition.

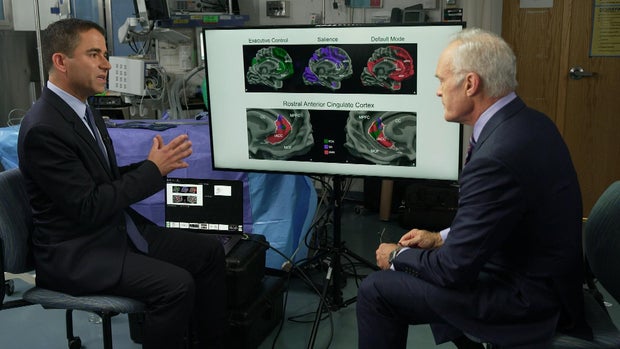

Harvard professor Dr. Brian Edlow led the research at Massachusetts General Hospital. He put the troops into scanners twice as powerful as a typical MRI and discovered changes in brain structure.

Dr. Brian Dr. Brian Edlow: And this particular region of the brain is critically important because it modulates emotion and cognition.

Scott Pelley: And a person who has pathology in that part of the brain would have what kind of symptoms?

Dr. Brian Edlow: They could have a broad range of symptoms that could include difficulty with higher level thinking or decision-making. They could have difficulty regulating their emotions. They could have disinhibition or difficulty controlling anger, for example.

Scott Pelley: And you put it all together and what do you find?

Dr. Brian Edlow: We find that blast overpressure waves may be penetrating the skull into the brain via the orbits, the eyes. Because this location within the brain is just behind the eyes.

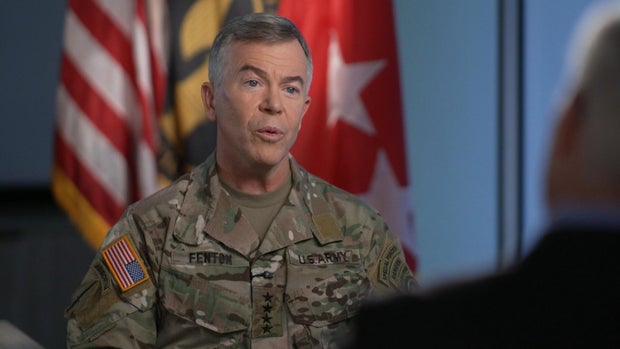

In 2023, Edlow showed that to Special Operations. A larger, long-term study will be needed to confirm the results. But Special Operations Commanding Gen. Bryan Fenton isn't waiting.

Gen. Bryan Fenton: There's a lot more questions than we have answers right now. But all of it, if I can put it into – into I guess, a summation, less is better in terms of exposure to blast overpressure. And we gotta get after that.

Today, Special Operations is testing a door breaching charge with half the blast pressure. Training rooms are now designed to absorb shockwaves. And they're training with no blast at all.

Gen. Bryan Fenton: Augmented and reality and virtual reality training. I think it's very important to us as we go forward.

And real weapons, modified for less shock, are being studied.

Scott Pelley: Can you be effective in the field with these modified weapons?

Gen. Bryan Fenton: We will not be in ineffective with these weapons. And if we are, we won't use that weapon. And we'll be able to accomplish the mission and protect our force at the very same time. And also, by extension, with the work we're doing, do that for the rest of the services.

The 'rest of the armed services' are modifying training and weapons, in part, because Frank Larkin pushed Congress to pass two laws requiring action. A new five-year study is being planned with 200 subjects. These are early days. Typical MRIs can't see the injury, so there's no test and no diagnosis. But if this is a turning point, it is thanks, in part, to a father who believed in his son.

Scott Pelley: Ryan is laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery, and I know that you go out there from time to time. I wonder what you say to him.

Frank Larkin: Well, I talk to him. First of all, I wanna make sure he's behavin' himself, And I told him that, you know, I'm not givin' up. And I gotta tell ya, Scott, he's here with us right now. You know, much of what I'm sayin' is him—his words— speaking through me. I didn't like what he did. I didn't support what he did. But I've grown to understand why he did it. And it-- he wasn't takin' the easy way out. It wasn't, you know, weakness. He was all about solutions. And this is how he was gonna get their attention.

Scott Pelley: Ryan accomplished his last mission.

Frank Larkin: To a great degree, yes. But we still have a ways to go. That will be accomplished when we see where these men and women are gettin' the care that they need. But more importantly, you know, buying down the risk on the front end with prevention. That's when we can slap the table.

If you or someone you know is in emotional distress or suicidal crisis, call the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 988 or 1-800-273-TALK (8255). You can also chat with the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline here.

For more information about mental health care resources and support, The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) HelpLine can be reached Monday through Friday, 10 a.m.–6 p.m. ET, at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264) or email info@nami.org.

Additional resources:

Suicide prevention: If you are a service member or a veteran and need someone to talk to, dial 988 and press 1.For other options, click here.

Recognizing the symptoms of blast exposure: If you are a service member, veteran or health care provider and you want to learn more about detecting the symptoms of blast exposure and traumatic brain injury, click here.

Brain health: To learn more about all aspects of the U.S. military's program aimed at enhancing brain health, click here.

Brain donation: For service members, veterans and their relatives, if you are interested in donating your brain for research into advanced traumatic brain injury, the Defense Department has established a brain tissue repository under the guidance of Dr. Dan Perl.

Produced by Henry Schuster. Associate producer, Sarah Turcotte. Broadcast associate, Michelle Karim. Edited by April Wilson.