"Very unattractive" workers can out-earn pretty people, study finds

A new study seems to show that, counter to prevailing economic wisdom and workplace lore, attractive people aren’t paid more just for being good-looking.

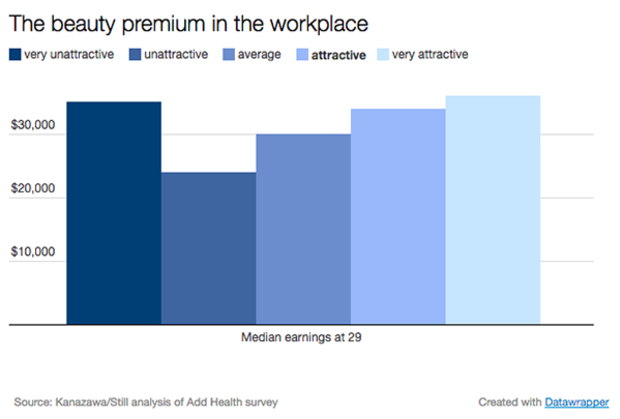

The “beauty premium” and “ugliness penalty” -- the idea that people’s income varies in part based on how attractive they are -- has been widely documented by economists. Good-looking people earn more than their plain counterparts, creating a difference of up to $230,000 over a working lifetime, according to one estimate.

Now, two researchers have thrown some cold cucumber water on that idea. In a study published in the Journal of Business and Psychology earlier this month, Satoshi Kanazawa and Mary Still found that people rated as attractive did take home more money than people rated unattractive. However, respondents rated as “very unattractive” -- a portion representing just 1 to 2 percent of the total study sample of 20,000 people -- earned more than those rated just “unattractive,” and in some cases even more than people deemed attractive. This is the first study to document a possible “ugliness premium,” the authors write.

Moreover, the earnings gap disappeared when the authors controlled for differences like health, intelligence and personality traits. In other words, the more attractive people “may earn more, not necessarily because they are more beautiful, but because they are healthier, more intelligent and have better personality traits conducive to higher earnings,” said Kanazawa in a press release about the study. Specifically, they are more extraverted and conscientious and less neurotic relative to other workers.

Not everyone is buying this, however. Because the portion of study subjects rated as “very unattractive” is so small, it has the ability to throw off the conclusions, said Daniel Hamermesh, a professor of economics at the Royal Holloway University of London. “One or two outliers in statistical work will give you a huge result, if [you’re studying] just a few people,” he said. For this reason, most studies combine “very” unattractive people with simply “unattractive” ones.

Hamermesh, who in the 1990s pioneered the economic study of beauty, or pulchrinomics, also noted that the Journal of Business and Psychology study differs from previous findings on how looks and earnings break down by gender. “Most research finds that the impacts of positive and negative looks are larger for men than for women,” he said. This study, by contrast, found the opposite.

So how do the mere average-looking masses get ahead? There’s one factor that outweighs beauty, Hamermesh has said, and that’s education. “Each additional year of education represents a 10 percent increase in earning potential,” he told the website LearnVest. So until the social safety net expands to cover universal beauty treatments, workers might want to rely on the power of the college degree.