U.S. "losing a generation" to fentanyl as agents fight Mexican cartels supplying the drug, DEA head says

We are in the midst of the worst drug crisis in U.S. history. The drug is fentanyl, and unlike cocaine and heroin, it's a purely chemical, man-made drug. It's cheap to produce, easily smuggled, and packs an incredibly addictive punch – 50 times more powerful than heroin. Nearly all the fentanyl flooding into the U.S. is made in Mexico by two powerful drug cartels, with chemicals primarily purchased from China. And as you're about to hear, it is frequently hidden in counterfeit pills made to look just like prescription drugs. It's the scourge of our time. Last year more than 70,000 Americans died from fentanyl; that's a higher death toll than U.S. military casualties in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan combined.

Angela King: We were so naive to fentanyl. We thought fentanyl, you hear about it, but you think 'Oh that's just affecting people on the streets, homeless people, drug addicts.' No. It is so insidious.

Angela King and Mike O'Kelley lost their 20-year-old son, Jack, to fentanyl last Thanksgiving. A junior at the University of Georgia, Jack had come home for the long weekend and was out late partying.

Mike O'Kelley: He was at a friend's house. So I had gone to bed a little worried.

The next morning he couldn't reach Jack, so he used "Find My iPhone."

Mike O'Kelley: I could see where he was. I texted the mother of the house who basically sent me a message back, 'Oh, we're not there. Door's unlocked. They're asleep.'

At eleven o'clock Thanksgiving morning, Mike went upstairs and found his son in bed… unresponsive.

Mike O'Kelley: I noticed his chest wasn't moving. So immediately pulled him out of the bed. Had, had performed CPR for 30-plus minutes.

Angela King: Mike called me and, screaming in the phone, "Jack's gone. Jack's gone." And I immediately rushed over there with one of our children. And the EMT had arrived and was working on Jack upstairs. And it was the most horrific, traumatic -- there's, there's not words.

Jack O'Kelley was captain of his high school football and lacrosse teams. He was studying business at Georgia, and was a popular member of his fraternity.

Bill Whitaker: Have you been able to piece together why take a pill? Was this his first time?

Angela King: I think he was just out having a good time and making, made a stupid mistake.

Mike O'Kelley: You know, the experimental days of taking drugs in college are over. They're all-- you know, all the pills are laced with fentanyl.

Mike and Angela found text messages between Jack and a drug dealer. He bought what he thought was Xanax, Oxycodone, and a gram of cocaine. But the death certificate states fentanyl was the cause of death.

Mike O'Kelley: He wasn't seeking fentanyl.

Angela King: He made a really bad decision. Not one that should have taken his life, though.

Bill Whitaker: Sounds like you've had a crash course in learning about fentanyl.

Mike O'Kelley: Absolutely.

Angela King: Absolutely. Which is shocking to me because at the rate that fentanyl is killing people in this country, it is absolutely ludicrous that this is not on the front page of every newspaper and every news broadcast daily.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid – a chemical cousin to morphine – originally designed for hospital patients in extreme pain. Now it is in cities and towns in all 50 states. Frequent users heat up fentanyl powder and inhale it. But more often it's sold in pill form – deliberately made to look like real prescription drugs – the one on the left contains fentanyl. Just two milligrams, an amount that fits on the tip of a pencil, can kill.

Anne Milgram: The cartels don't sell fentanyl as fentanyl. They hide it in other drugs like cocaine or methamphetamine or heroin. They make it into these fake pills that look identical to pharmaceutical drugs that Americans would recognize, like Oxy or Xanax, Percocet, Adderall. It will be a very massive high that is very short. And that person, they're betting if they survive, will come back again and again and again to buy more.

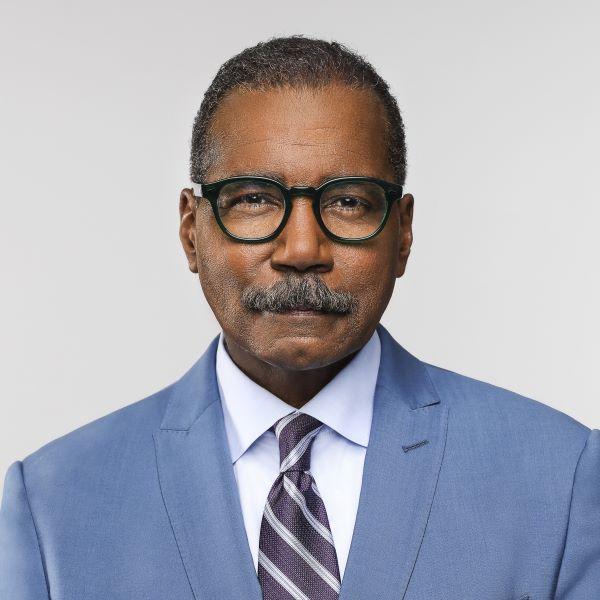

Three years ago, Anne Milgram – a former attorney general of New Jersey – took over the Drug Enforcement Administration. Since then fentanyl has claimed more than 200,000 American lives, although deaths appear to be leveling off.

Anne Milgram: Fentanyl is impacting every part of the United States. It's impacting our communities. It's impacting our kids. It's impacting our economy. One of the things that I've learned over the last few years that really stays with me is every single week we lose 22 teens between the ages of 14 and 18.

Bill Whitaker: Every week.

Anne Milgram: Every single week we're basically losing a high school class somewhere in America.

She started putting pictures of people who died from fentanyl in the lobby of DEA headquarters, a daily reminder of the drug's catastrophic impact.

Anne Milgram: We're losing a generation.

Bill Whitaker: That's what this says.

Anne Milgram: Yes. You can see it so clearly when you look, and you see Americans from all walks of life, all states, all communities, young and old, every background possible. We have folks in military uniforms, we've got babies.

Bill Whitaker: Oh my God!

Bill Whitaker: Someone who just picks up the pill that a parent dropped.

Anne Milgram: Yes.

The DEA is part of the Department of Justice and conducts intelligence gathering and counter-drug operations worldwide. Milgram oversees 10,000 employees.

Anne Milgram: As complex and as massive a problem as this is, it's also not a whodunit. We know who's responsible. It's the Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco Cartel that are based in Mexico. They dominate and control the entire global fentanyl supply chain, starting in China, going to Mexico, coming into the United States.

Milgram told us this crisis began 10 years ago… when the cartels started to wrestle control of the supply chain from China and began making fentanyl in clandestine labs in Mexico.

Bill Whitaker: So these two drug cartels from our neighbor, from Mexico, are responsible for almost 70,000 American deaths a year?

Anne Milgram: Yes.

Bill Whitaker: How do you fight that?

Anne Milgram: We've taken action over the last three years against every single part of that global supply chain, charging Chinese nationals with selling fentanyl precursors, charging and indicting, investigating, members of these cartels at every level and then finally taking hundreds of millions of deadly doses of fentanyl off American streets. And we are making progress but there's so much more that needs to be done.

Troy Miller: The majority the fentanyl that we're seeing, about 90%-plus is coming in passenger vehicles.

Commissioner Troy Miller, a 30-year veteran of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, told us almost all the fentanyl coming into the country is smuggled through legal ports of entry like here at San Ysidro, between San Diego and Tijuana. It's the busiest land port in the Western Hemisphere.

Bill Whitaker: What percentage of the smuggled fentanyl do you think you are catching?

Troy Miller: You know, Bill, I, I don't know what percentage we're, we're catching. But I can tell you we've seized 27,000 pounds of fentanyl in fiscal year of 2023.

Miller took us for a bird's eye view to see the magnitude of the challenge.

Troy Miller: So this, this is the wall. It comes right up to the port of entry and resumes here. That's Mexico.

More than 60,000 cars snake through 34 lanes 24-7. Officers have a minute or less to decide who gets a second look, and they only have the resources to search 8% of the cars. Dogs trained to sniff out fentanyl are some of their best assets. The cartels are constantly adapting, for example, hiding pills in gas tanks to mask the scent.

Troy Miller: So we're in the seizure vault...

Commissioner Miller showed us rack after rack of seized drugs locked in this massive vault. For security reasons, we agreed not to divulge its location.

Bill Whitaker: So explain to me why the smugglers would use the busiest port as their main smuggling route. I mean, it seems counterintuitive. Why not do it some place much less conspicuous? Why not come across the desert?

Troy Miller: Well, in the San Diego field office, we're seeing 200,000 people a day. Every one of these 200,000 people is presenting themselves as a legitimate traveler.

We were astonished to learn two-thirds of the people arrested smuggling fentanyl are American citizens paid by the cartels.

Troy Miller: We've seen terrible trends. We've seen high school and middle schoolers smuggling fentanyl and dropping it off to a cartel member at a high school.

Bill Whitaker: Do you have the budget and the manpower you need?

Troy Miller: I've been very clear that Customs and Border Protection needs more officers. We need more agents. We need more intel research specialists to distill that information.

We asked him about the bipartisan border bill killed by the Senate at the urging of former President Donald Trump. It would have provided 1,500 new border and customs officers and 100 high tech detection machines.

Bill Whitaker: …The bill had money for much of the stuff you're talking about. Is the political inaction, is that costing lives?

Troy Miller: Again what I can say is we need more resources to do our jobs. And we need to all get on the same page and tackle this together.

Sherri Hobson saw the fentanyl crisis coming. As an assistant U.S. attorney in San Diego she prosecuted Mexican cartel cases for 30 years before retiring in 2020.

Sherri Hobson: Cartels are very business-oriented. They look for profit. They look for perpetual power. They're institutionalized.

Bill Whitaker: So it sounds like you're saying they're very sophisticated.

Sherri Hobson: They are. They do their homework. They do their analysis.

She says the cartels' move into fentanyl was entirely predictable. When the U.S. opioid crisis triggered a crackdown on the drug industry and many companies were sued by ravaged communities, the supply of legal opioids dried up – but the demand from Americans addicted to the drugs did not.

Sherri Hobson: It's very strange to think that the pharmaceutical industry basically set the table for the Mexican cartels to come in and dominate.

Bill Whitaker: That's, that's, that's incredible.

Sherri Hobson: It is. So I think what happened was they said, "You know what? We have an open market. We have millions of people that are addicted to Oxycodone. We can do fentanyl. We can create these counterfeit pills and we can, we can sell them."

Bill Whitaker: So the Mexican cartels just filled this vacuum.

Sherri Hobson: Filled the void, filled the vacuum.

Anne Milgram: So the opioid epidemic definitely started this arc that we're on.

The head of the DEA, Anne Milgram, agrees the U.S. drug industry bears a lot of blame for igniting the crisis, but says social media companies are fueling it today. The companies say they're taking steps to combat this.

Anne Milgram: And what's happening on social media? The cartels use it to organize themselves to get individuals who will carry the drugs across the border from Mexico, to post ads for drugs, and to sell drugs. Whether it's SnapChat, Instagram, TikTok, there are drugs being sold there every single day.

And seven out of 10 of those counterfeit pills the DEA tests have a potentially deadly dose of fentanyl. Angela King and Mike O'Kelley say that's information every American needs to know.

Mike O'Kelley: It's a war. It's, it's a new drug war. And that drug war is totally different than anything we've ever dealt with before 'cause now we're losing our young ones. Whatever the government's trying to do, I'm glad they're doing something. It just doesn't seem to be enough.

Editor's Note: Troy Miller's official title is senior official performing the duties of the commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Produced by Graham Messick and Scott Higham. Associate producer, Jack Weingart. Broadcast associate, Mariah Johnson. Edited by Matthew Lev.