Unemployment could plague U.S. after jobs return

(MoneyWatch) America is facing an unemployment problem far more complex than what emerges in government jobless statistics. Changes in who the unemployed are and what has happened to them in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis could mean a starkly different economy even after jobs have returned.

Going just by the numbers. it might appear things are getting better, or at least not getting much worse. The unemployment rate dropped in August to 8.1 percent, from 8.3 percent. Yet the main reason for that decline was that many job-seekers gave up looking for work. A more accurate picture is visible in the four-week average of the number of people applying for unemployment benefits. The Labor Department said today that nearly 378,000 Americansapplied for jobless aid last week, the highest level in nearly three months and the fifth-straight week that figure has increased.

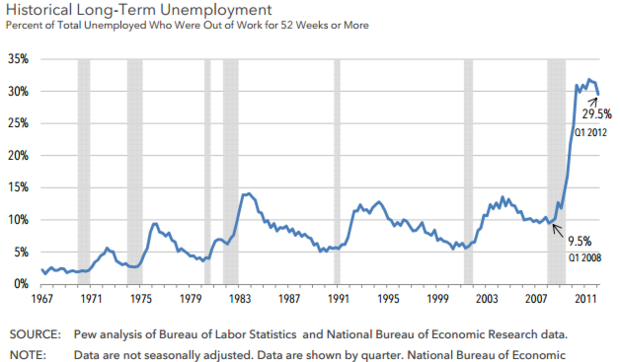

It isn't just the number of people out of work that matters; it's also how long they've been out of work. Of the nearly 13.3 million unemployed people in the U.S., 5 million, or 40 percent, have been without a job for more than six months, according to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. Of this total, 4 million, or 29 percent, have been jobless for a year or more. This is near the all-time and three times the rate at the start of the Great Recession in 2008. It currently takes an American 39 weeks to find a job after being fired.Poverty remains level, but incomes fallWhat do Americans think of the rich?Is the U.S. economy healing or coughing blood?

The longer people are out of work, the harder it is for them to eventually make their way back into the labor force. And when they do find a job, it is typically for lower pay than what they previously earned. That doesn't only hurt individual households -- it's problematic for the entire U.S. economy, too, since employees facing lower wages and salaries are likely to reduce their spending, a serious challenge for a country that depends on personal consumption to drive growth.

It's well known that job losses have been lower among more highly educated people. In August, the unemployment rate for those with only a high school diploma was 10.3 percent, while for those with college degree it was 4.3 percent. But that disparity levels out once people lose their job.

An unemployed person with a doctorate has roughly the same chance of being out of work for more than a year as someone who hasn't finished high school, according to Pew Research Center. In fact, an unemployed worker with a PhD is slightly more likely to have trouble finding work again. That's because employers believe that the skills of these so-called knowledge workers decay the longer they are out of work.

Highly educated workers are also at a disadvantage because of the time required to acquire that education. Once older workers lose their job, meanwhile, they are are far more likely to enter the ranks of the long-term unemployed than younger workers are.

People returning to work after a long period almost always earn significantly less than they did before. The larger pool of job candidates, along with huge gains in worker productivity over the last decade, has caused the median income in the U.S. to fall. The median annual household income last year was $50,054, down 1.5 percent from 2010, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. It has now fallen back to the level it was at in 1996. This is shrinking the middle class as an income group and, perhaps even more fundamentally, may even be changing Americans' social identity.

Since World War II, most Americans have described themselves as belonging to the middle class. Indeed, the percentage of people who identify themselves as middle class has traditionally far exceeded the statistical definition of this group as measured by distribution of income. But that seems to be changing.

Pew, a nonpartisan think tank, also has found that nearly a third of Americans now describe themselves as belonging to the lower class -- that is up from 25 percent at the start of the recession.

About three-quarters of those who think of themselves as lower class say it's harder to get ahead today than it was 10 years ago. Only half believe hard work brings success, a view expressed by overwhelming majorities of those in the middle (67 percent) and upper classes (71 percent). People in the lower classes are also significantly more likely than middle- or upper-class adults to believe their children will have a worse standard of living than they do, Pew's research shows.

The expectation that each generation will surpass their parents is, of course, central to the American Dream. But with the middle class shrinking and the lower class expanding, that defining social and economic narrative in the U.S. may soon need revision.