"Doctor detectives" help diagnose mysterious illnesses with DNA analysis

For years, the Miller family has faced an uphill battle trying to find a diagnosis for their two sons, Carson and Chase. The boys, now 5 and 6 years old, have been unable to walk, stand or speak since birth. Originally they were diagnosed with cerebral palsy, but their parents felt their symptoms didn't match up, reports CBS News contributor Dr. Tara Narula.

"There were many nights when we were up wondering, why this is happening?" father Danny Miller said. "Why can't the doctors help us? What else can we do?"

The family eventually applied to the Undiagnosed Diseases Network, or UDN, where so-called "doctor detectives" attack medicine's toughest cases by offering families access to cutting-edge genetic research at no cost.

The network of doctors across the country was set up by the National Institutes of Health in 2014 and is funded by taxpayers. For patients whose symptoms have stumped medical professionals, the group is often their last hope.

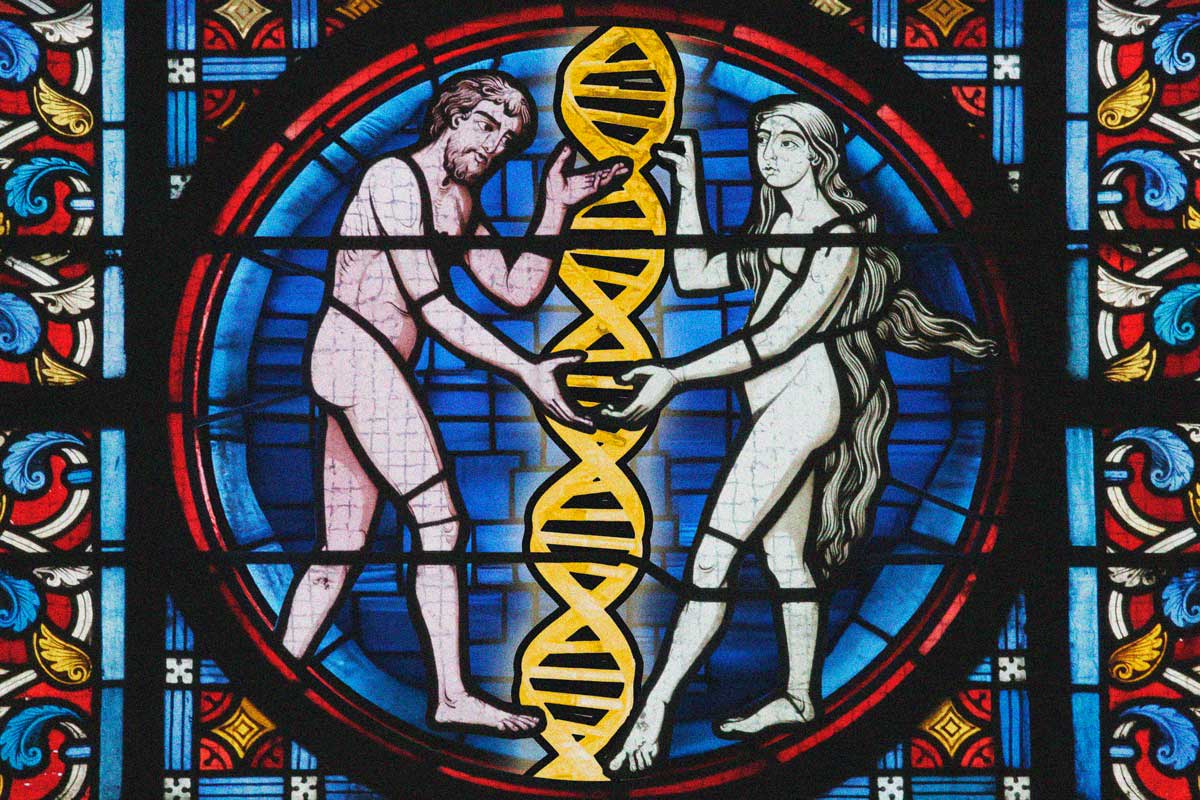

Wednesday's report in the New England Journal of Medicine says the group has completed evaluations on 382 patients and diagnosed more than a third, often through DNA analysis that uncovers a rare genetic mutation. Dr. Jon Bernstein works at the network's Stanford site.

"For some of our patients, we've looked at the genomes of all of the microorganisms that may live on their blood or in their body," Bernstein said. "Ultimately what we are really trying to do is find patients who are similar to each other… That's really what the foundation of diagnosis is."

The report also says nearly 60 percent of the network's diagnoses lead to recommendations regarding a change in therapy or treatment.

Earlier this year, doctors found a gene mutation in the Miller brothers, leading to a diagnosis of MEPAN syndrome – a rare metabolic disorder.

"We actually have a chance at helping the boys figure this out," mother Nikki Miller said. "There's going to be some next steps here, there's going to be people that hopefully we'll be able to talk to now because we have a leg to stand on having a diagnosis now to look at."

The Millers say there are no proven treatments currently available, but the diagnosis will help them build a coalition to fund future research.

"The more parents you have, the more families, the more resources, the better your chances are of securing funding. We've come a long way and it's through programs like the UDN that I think is putting some sense around all of this," Danny said.

Doctors say every new diagnosis adds to their understanding of these rare diseases and how to detect them. The network can't take on every case, but it's received more than 2,700 applications, a number that continues to grow.