Experimental ultrasound treatment targeting brains in trials to help those with Alzheimer's, drug addiction

A man with Alzheimer's, knowing there's no cure for the disease, donned a million-dollar helmet for a cutting-edge treatment directing nearly a thousand beams of ultrasound energy at a target in his brain the size of a pencil point.

Dan Miller, 61, said he didn't have anything to lose when he signed up for the experimental procedure, pioneered by Dr. Ali Rezai, a neurosurgeon. Doctors have used ultrasound for 70 years to get better views of organ and fetal development. Rezai is testing it now as a treatment tool for people with Alzheimer's and those battling drug addiction.

"There's no miracle cures here," Rezai said. "It's advancing medicine with calculated risks and pushing the frontiers."

Could ultrasound help people with Alzheimer's disease?

Miller was one of three patients in Rezai's trial at the Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute in Morgantown, West Virginia. Rezai allowed 60 Minutes to witness his revolutionary attempt to use ultrasound to slow down the cognitive decline of people with Alzheimer's disease.

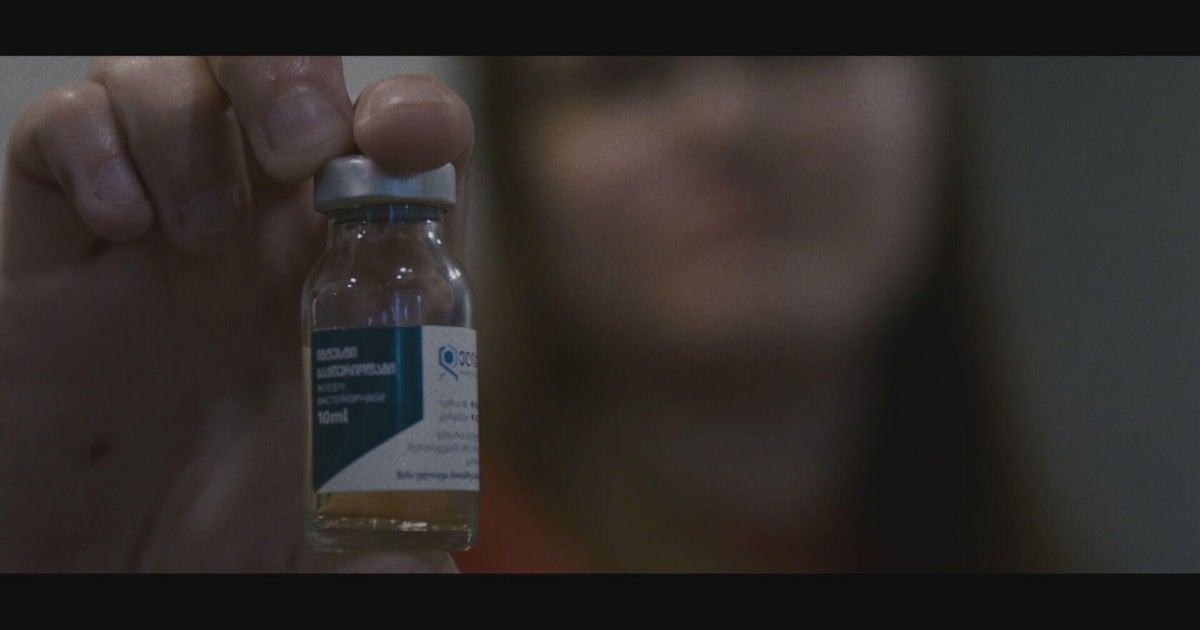

A scan of Miller's brain revealed red spots, indicating a build-up of beta amyloid proteins, a sort of "brain plaque" that's believed to play a major role in those with Alzheimer's by disrupting communication between brain cells. In the hours before the experimental procedure, the trial patients get an IV treatment of aducanumab, a drug used to reduce the plaques.

Aducanumab works slowly in the way it's normally administered, when people get an antibody infusion over an hour or two once or twice a month for 18 months or longer, Rezai said. It takes so long because the drugs have a hard time getting through what's called the blood-brain barrier.

In July, the Food and Drug Administration also granted traditional approval to the Alzheimer's drug lecanemab, known by the brand name Leqembi, after an accelerated approval was issued in January of 2023.

Rezai uses focused ultrasound to open the blood brain barrier. The patients in his trial put on a specialized helmet and lie down on an MRI table. Once inside, they get an IV solution containing microscopic bubbles. When hit with ultrasound energy, the bubbles vibrate and pry open the blood-brain barrier, temporarily allowing the therapeutic drugs to quickly get inside the brain.

"This way we're getting the payload, the therapeutic payload, exactly to the area it needs to go with a high penetration," the neurosurgeon said. "But we've got to be careful because we want to be safe about this. You don't want to deliver too much, don't want to open the blood-brain barrier too much."

If the barrier is opened too much, it can result in bleeding and swelling in the brain, Rezai said.

Even though Rezai's trial patients were awake during the procedure, they said they didn't feel a thing. They each received the treatment once a month over a six-month period.

So far, there has been no change in the ability of the three patients to do their daily activities since the ultrasound treatments ended in July, Rezai's team said. Patient brain scans also show a clear reduction in beta amyloid proteins; the beta-amyloid plaque targeted with ultrasound were reduced 50% more than areas targeted by infusion alone.

Now that Rezai has shown focused ultrasound can clear beta amyloid plaque faster, he has Food and Drug Administration approval to use ultrasound to try and restore brain cell function lost to Alzheimer's.

"We don't know if it's going to reverse the damage to the brain, because Alzheimer's, the underlying cause, is still occurring," Rezai said. "So we have another study that we're looking at with ultrasound. First, clear the plaques, then deliver ultrasound in a different dose to see now if we can reverse it or boost the brain more for people with Alzheimer's."

But Rezai isn't just working to help people with Alzheimer's. He and his team are also targeting drug addiction, a disease that affects around 21 million Americans. Rezai is also using ultrasound for the addiction treatment.

Treating addiction with a brain implant

Before he came around to the concept of using ultrasound for addiction treatment, Rezai started with the notion that he might be able to adapt technology used to treat Parkinson's disease to help treat people with severe drug addiction. For Parkinson's, a brain implant is used to stop shaking. Rezai thought to use a similar implant in the part of the brain responsible for behavioral regulation, anxiety and cravings as a way to target addiction.

"There's a specific part of the brain that is electrically and chemically malfunctioning that is associated with addiction," he said.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse agreed to support his research and, in 2019, the Food and Drug Administration gave Rezai a green light for the research.

Gerod Buckhalter agreed to be the first addiction patient in the U.S. to get the implant surgery. He got hooked on painkillers after a shoulder injury and dealt with addiction for more than 15 years. Buckhalter couldn't stay clean for more than four days at a time, he said. He does not remember how many times he overdosed.

"I didn't know where I was gonna sleep some nights. You know, my family didn't want me around anymore," Buckhalter said. "I just, I did so many things to hurt them that, you know, it was just too much for them to deal with."

He was introduced to Rezai four years ago. The neurosurgeon operated on Buckhalter during a seven-hour surgery so new that it didn't have a name yet. Rezai opened a nickel-sized hole in Buckhalter's skull, then directed a thin wire with four electrodes deep inside. Buckhalter was awake during the surgery.

Once in place, the wire was connected to a device placed below the collarbone. The electrical pulses it sends to the brain are intended to suppress cravings. Buckhalter said it was painless, post-surgery. The system is adjusted remotely with a tablet computer as needed.

There was an immediate change when they turned the system on after the surgery.

"Just felt better, you know, just felt like I did prior to ever using drugs, but a little bit better," Buckhalter said. "And it was at that point that I knew that I was going to have a legitimate shot at doing well."

In all, four patients with severe drug addiction had the implant surgery: one had a minor relapse, another dropped out of the trial completely, and two, including Buckhalter, have been drug free since their operations.

How ultrasound treatments may help people with drug addictions

Opening someone's skull is always risky. Rezai thought he could reach more patients quickly if he utilized ultrasound technology, which he was already using to treat other brain disorders.

"There's no skin cutting. There's no opening the skull," he said. "So it is brain surgery without cutting the skin, indeed."

In the new trial, he and his team treat addiction by aiming hundreds of beams of ultrasound to a precise point inside the brain.

"So the area that we're treating is the reward center in the brain, which is the nucleus accumbens, which is right down at the base of this dark area," Rezai said. "And then we deliver ultrasound waves to that specific part of the brain, and we watch how acutely, on the table, your cravings and your anxiety changes in response to ultrasound."

The entire procedure takes an hour, Rezai said.

Last February, Rezai used the focused ultrasound to treat Dave Martin, who was surrounded by friends and family who used drugs his whole life. Martin said he began using drugs at age 7 and continued for 37 years. A lot has changed for him since the ultrasound treatment.

"The day of the procedure, it was the best day of my life," Martin said.

According to Dr. Rezai's team, Martin did admit to taking one pain-killing pill at a party in December. Still, 10 of the 15 patients in the ultrasound clinical trials have remained completely drug free.

What's next for Rezai's ultrasound treatment?

Rezai is trying the same therapy on 45 more addiction patients and is already thinking about expanding the use of ultrasound to help people with other brain disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder and even obesity.

He's determined to learn more and replicate his findings.

"There's always risk, but you cannot advance and make discoveries without risk," Rezai said. "But we need to push forward and take the risk, because people with addiction and Alzheimer's is not going away. It's here, so why wait 10, 20 years? Do it now."