Ukrainian widows, children work to overcome grief, trauma at climbing camp in the Austrian Alps

This is an updated version of a story first published on Nov. 26, 2023. The original video can be viewed here.

A bus filled with widows of war and their children left Ukraine bound for the Austrian Alps. They'd been invited to a charity summer camp hosted by Nathan Schmidt, an American Marine who knows, all too well, the bereavement of war. As we first told you last fall, mountain climbing was Schmidt's path to recovery from three combat tours in Iraq. And so, when Vladimir Putin launched his attack on an innocent people, Schmidt offered Ukraine what seemed like an impossible hope—that, in only six days in the Alps, he could teach grieving families to rise.

The journey to an Austrian hotel ended at 3 in the morning after 45 hours on the road. So, the trip already felt like a mistake to widows who packed enough skepticism to last the week. Their husbands died defending Ukraine-- among the tens of thousands of Ukrainian soldiers killed. Time stopped for Natalia Zaremba and her two young boys. She told us...

Natalia Zaremba (translated): I think they still don't believe what happened. Just like me, they're still waiting for daddy to come home from work

For daddy to fly home to 8-year-old Illia and 5-year-old Andrii who imagined mastering the air like their dad. Mykhailo Zaremba was a navy pilot shot down, May 2022--in the unprovoked invasion of his home.

Natalia Zaremba (translated): He loved Ukraine, so, he gave his life for Ukraine.

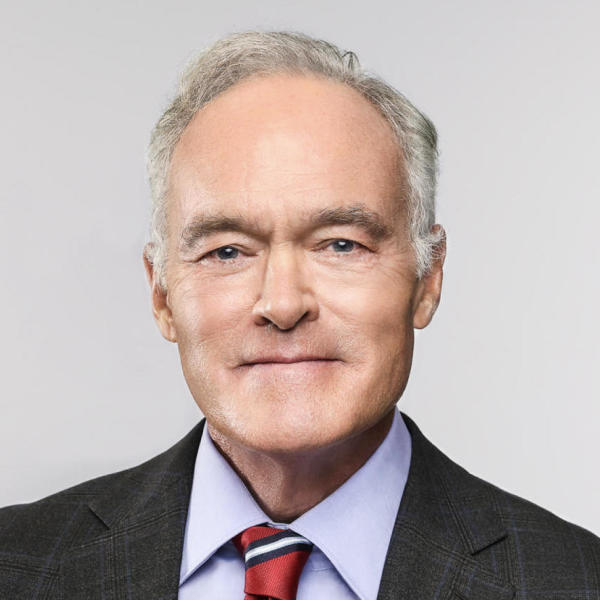

Scott Pelley: What is your hope for this trip?

Natalia Zaremba (translated): I want to find strength for myself to be able to bring my children up, to bring our children up. I want to find the strength to not let my husband down, and to give our children a good future.

Thirteen widows and 20 children had come to Austria from Mykolaiv, a city bombed by the Russians for 260 days. The bereaved families traveled 13-hundred miles on faith to meet a stranger still struggling to heal from his own war.

Nathan Schmidt, Naval Academy graduate, lieutenant colonel U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, led shouts of glory to Ukraine at the third summer camp hosted by his small charity, the Mountain Seed Foundation.

Nathan Schmidt: It comes from the Bible. It was, you know, "With faith the size of a mustard seed, one can move mountains." We're not-- we're not a religious organization, but that faith-- that faith in something bigger, that faith in self. And if you can reinforce that faith -- we and you can move mountains.

Scott Pelley: What do you hope these families have when they return to Ukraine?

Nathan Schmidt: We teach, we teach about the significance of the rope in mountaineering. The rope signifies community, it signifies team. You're never alone on the rope. It also signifies courage. Because when you're on the rope that means you're climbing a mountain. And courage doesn't mean that you're not afraid. It actually means that you are afraid and you're gonna overcome that fear.

There would be plenty of fear to overcome because, ultimately, this was his goal. To lead children on the last leg of a climb to the peak of Mount Kitzsteinhorn—at more than 10,000 feet. The first steps to the summit began with training for the kids, ages 5 to 17.

For their moms, there were daily group therapy sessions. And every day of the camp would raise the challenge for both.

Nathan Schmidt: We're gonna trust ourselves, the main thing, we're gonna trust our equipment, and we're going to trust the team that we're with.

The team of professional guides and other volunteers included Dan Cnossen. Cnossen was Schmidt's Naval Academy classmate. As a Navy SEAL in 2009 he lost his legs in Afghanistan. He's a three-time paralympian, but he'd never climbed since his injury.

The first days of training looked dangerous.

But there was always an expert on the rope—

One professional guide for every four children who eased the tension slowly for kids including 14-year-old Myroslav Kupchenkov.

Guide: Now just lean back, lean back, totally trust.

Myroslav Kupchenkov: No, I can't.

Guide: You can.

Myroslav Kupchenkov: I can't.

Guide: You can.

Myroslav Kupchenkov: I CAN'T!

Guide: Of course you can.

Myroslav, his adult sister and their mother, Natalia, lost Oleksandr Kupchenkov, a 53-year-old career soldier.

Natalia Zaremba (translated): He was the man I wanted to spend my whole life with. He was the best at everything, wonderful husband, wonderful dad. People loved him.

Kupchenkov was hit by a Russian missile, March 2022, as he was running ammunition to his pinned-down soldiers.

Myroslav Kupchenkov (translated): Every day he showed me how to be a good person. And he was always brave. He would never go back – only forward.

And Myroslav discovered, in rappelling, going back is going forward and terror was just one step before triumph.

Guide: That's it. There you go, super!

As the children learned the ropes, the moms seemed to be near the end of theirs.

Amit Oren: It will be hard for you to hear this…

They were led by clinical psychologist Amit Oren, with translation by Iryna Prykhodko, the charity's Ukrainian co-founder. Amit Oren is an assistant professor at the Yale School of Medicine.

Amit Oren: The way I approach this group of people is not in looking at their trauma; it's in looking at their strengths.

Scott Pelley: And what strengths are you finding?

Amit Oren: Capacity for love, honesty. These are the strengths that they're finding. All I do is take a flashlight, illuminate inside them, and let them see and remember who they are.

But Svitlana Melnyichuk, on the left, didn't see the light. She didn't believe in breakthroughs. She brought her daughter Myroslava while her adult daughter stayed home. Svitlana lost her husband, Yuriy, a civilian building inspector who volunteered the day after Putin invaded. Svitlana mixed homemade explosives for the troops as her husband sent text messages from the front. Svitlana told us:

Svitlana Melnyichuk (translated): Pictures started coming in "Good morning darling" with a photo of a flower taken right from the trench. It was spring already, right from the trench.

The photos thrilled her because Yuriy had always worked too much, at the expense of the family, she thought. But after the invasion family was all he cared about. His revelation lifted their lives. Then he was dead. and her rage is almost like blindness.

Svitlana Melnyichuk (translated): I became very distant and angry, and I kept all the sorrow inside. I didn't share it.

Nathan Schmidt was keeping his sorrow inside when in 2019, a friend invited him on a climbing trip. Schmidt wasn't a mountaineer. He's afraid of heights. to him, the idea sounded so difficult and frightening it might just have the force to break his grief.

Nathan Schmidt: Yeah. You know, I spent the Naval Academy preparing myself for war, and nothing can prepare yourself for war.

In 2004, Schmidt was a 24-year-old first lieutenant who dreamed of leading marines. He landed in Fallujah, on the eve of the bloodiest battle of the entire Iraq war.

Nathan Schmidt: Two weeks after arriving in--at Camp Fallujah I lost my teacher who was a mentor of mine at the Naval Academy.

Scott Pelley: Killed?

Nathan Schmidt: Yeah. The rocket struck the office. I was the second one in the room. And-- and it was the first time I had ever seen anyone die in such a way. And-- and it was my teacher. And that established a crack in me that had to be healed in another way that took years and years to heal. The problem was that, that was the first of many cracks. I lost one of our Marines that was in my unit a month later. I then had my friend lose his leg. I took over his team. A few days after that, I lost my analyst in the gun turret of our vehicle. By the end of November, the unit that I was with, which is a great unit, 3/1-- was combat ineffective. We had lost over 20% of our unit either injured or killed.

And that was his first tour. He fought in Iraq for three years.

Scott Pelley: Who were you after that third tour?

Nathan Schmidt: I thought in my mind that I was the strongest, but in reality, I was – I was the weakest. I was strong physically. I could do as many pull-ups as you asked me to do. I could run. But, yeah, I was broken. And you know, and those cracks, they take a lifetime to heal.

Scott Pelley: You spend this week doing what you can to heal these families. And I wonder how much of that is healing you.

Nathan Schmidt: It's huge. This program has healed me in ways that I can't even describe. And then I feel sometimes like it's selfish. You're right, you're right. It works. And I'm not sure why.

Maybe it works because the children and mothers who arrived on the bus will not be the same people who return to Ukraine. No one's quite the same after scaling a wall like this.

Nathan Schmidt's week-long summer camp for bereaved Ukrainian children and their mothers began with training in the Austrian Alps. Then, serious work began—the kind of challenge that might rise to a revelation.

The Hohe Tauren National Park embraces some of the highest peaks in the Austrian Alps and a feat of engineering. The Mooserboden Dam would be the first big challenge for the 13 widows and their 20 children. A zipline flew them to the concrete face.

…where they found a steel cable to clip their harnesses to. Footholds were set across the span about two-and-a-half football fields wide. The children and moms literally could not fall. and yet, the Mooserboden Dam remained 32 stories of doubt.

Natalia Zaremba did not like the measure of it. The Russians had killed her husband, the father of her two boys. Was this risk foolish?

Scott Pelley: Why do you put them on this dam?

Nathan Schmidt: We put them on this dam because we want them to confront discomfort. We want them to confront their fears.

Nathan Schmidt co-founded the Mountain Seed Foundation charity. We met in the 700-square mile park where the dam, finished after World War II, is a tourist attraction for rock climbers.

Scott Pelley: What makes this safe, in your view?

Nathan Schmidt: First off, we have professional mountain guides. The second thing is, all the equipment that we have, they trained throughout the week on it. They know how to use the equipment. And then particularly the little children, they are also short roped into a guide. So, there's multiple layers of security for them.

And so, with all that security…. the challenge was not so much under their feet, as under their skin.

Myroslav Kupchenkov who told us his late father "never went back—always forward"—was following his father's lead.

Nathan Schmidt: You know, in life sometimes the thing that gets you through a difficult point is knowing that you've already done something more difficult.

Scott Pelley: What difference do you see in them when they reach the top?

Nathan Schmidt: The sheer look of joy on their faces…

Nathan Schmidt:…It's hard to even comprehend. And we know that will be a strong point for them when they go back to Ukraine. They will know that they've conquered this wall, and they will-- they've conquered their own fears.

Fears conquered by Natalia Zaremba who, at the end of the climb, was walking on air.

She told us she came to Austria to find strength to raise her boys alone.

Natalia Zaremba (translated): It was something incredible. As soon as I stepped on the ground, the children ran to me, hugged me. There were no flowers there, so my older son gave me a branch from a bush.

Scott Pelley: You know, I see you smiling. And I suspect there hasn't been a lot of that.

Natalia Zaremba (translated): I don't feel joy the way I used to. Wherever I am, no matter how good a time I'm having, it's hard knowing my husband could have been with us. But he's not. And even when I smile, the pain in my heart is very strong.

The pain is strong but maybe not invincible. Natalia was listening at the meetings. and words of inspiration, like those of Navy SEAL Dan Cnossen, were getting through.

Dan Cnossen: That bomb in Afghanistan took my legs and I can't change that fact, but ultimately it has to be up to me to decide if it's going to take the rest of my life too. Thank you all very much.

Still for others, especially Svitlana Melnyichuk, words fell short. She had told us her husband sent photos of flowers from his trench until the Russians killed him. She said…

Svitlana Melnyichuk (translated): Life is a book that you read your whole life. When my husband died, I stopped turning the pages in the book.

But opening a new chapter is what clinical psychologist Amit Oren had in mind—and so she took the widows to a storybook castle. where she hoped to scale the walls of Svitlana Melnyichuk.

Amit Oren: And I started to talk with her about castle walls, that we're going to see a castle, where there are always very deep, tough, impenetrable walls, and that I thought that her face looked like that, that it was hard to see what's inside, like this castle. And I brought them to a wall-- a side wall of the castle, where there are teeny, tiny windows And I said to them, "Right now, I think you're here at the bottom. And as you go up, you're able, then, to see three windows" I said, "Unless you open that window, you can't peer out and see the beauty around you. You're trapped." And ultimately what happened is several of the women stood there on the grass and opened up to each other. She was one of them.

Amit Oren: It was choking you, It was choking you.

Svitlana Melnyichuk (Ukrainian): Da. Da.

The next day, after the group session, Svitlana had been thinking.

Amit Oren: She came up to me and said to me, "It was a very painful conversation we had. And I made a decision. My anger was choking me. And I decided to let it go so I can breathe."

Amit Oren: Congratulations. You've done hard work. I'm so happy for you.

Amit Oren: She has a long way to go. But she's understood that it's a choice, at least, the few things she can control in this world is how open or closed she chooses to be in her own castle.

Nathan Schmidt: You know as you talk to the mothers none of them expected what happened in February of 2022.

Scott Pelley: The invasion?

Nathan Schmidt: Losing their homes, in many cases losing their future, or at least the future being unknown. And it's one of those moments in climbing where you look all around and you don't know where you're gonna put your hand, and you don't know where you're gonna put your foot. You don't know if you're gonna be able to stay in that position or fall. This program is meant to show them the footholds and the handholds to fill the cracks that they have too. And then lead their children back up-- up the mountain.

On day five, one mountain remained. Nathan Schmidt took the first steps from a high tram station on an ascent to the peak of Mount Kitzsteinhorn. It was a steep and icy 570 feet to the ultimate test of the camp.

Like the dam earlier, there was a fixed cable to hook onto. But, like the dam, glancing down looked fatal. And looking up-- a cold, thin glare exposed hours of struggle. We followed Schmidt's lead and remembered what he told us about the rope we were on and its three lessons, community, courage…

Nathan Schmidt: And the last thing is responsibility. And this is probably the most difficult one. And that is, when you're on the rope you're responsible for those that are on the rope with you. When they're weak you pull them up. When they are showing signs of fatigue, you encourage them.

Nathan Schmidt: Look at me, Ivan. "Breathe in, 2, 3, 4, hold 2, 3, 4…

Nathan Schmidt: We hope that when they go home, that they build their own communities, they add people to their rope that they encourage them to face their fears and have courage.

Courage lifted them 10,508 feet—a summit reached by everyone.

Nathan Schmidt: Let's go Dan!

Including, Nathan Schmidt's Naval Academy classmate, Dan Cnossen on his prosthetics.

Dan Cnossen: It was tough, it was tough but I'm happy to make it to the top and it was great to do it with everyone, seeing the kids climbing gave me a lot of inspiration to keep pushing.

Natalia Zaremba's kids pushed to the top. She had come to Austria to find strength within herself. but, from the peak, she could see where that kind of strength truly comes from.

Natalia Zaremba (translated): We have something that bonds us more now, some new achievements, which we experienced together and that taught us to be braver and stay together, because only together can we overcome this. Our strength, SHE SAID, will be from being together.

Also among the climbers at the summit, was Myroslav Kupchenkov, who told us, now, he could do anything.

Scott Pelley: What is your hope for them?

Nathan Schmidt: My hope for them is that they can remember the achievement that they've, they've had and I also hope they remember the stillness and the peace of these mountains. You can't hear the sounds of war here. You just close your eyes, and you feel like you could fly.

Even Svitlana Melnyichuk took flight—rising, to the summit and, at last, to the high, open windows of her castle.

Svitlana Melnyichuk (translated): I was screaming, to be honest I was simply screaming. Having breathed in full lungs of air, I was screaming with my head up toward I don't know, God, nature, I don't know. I was just getting rid of all the negative.

Scott Pelley: Has this helped you in some small way to heal?

Svitlana Melnyichuk (translated): Oh. Well, at least I managed to open the bag of my sorrows.

To open their sorrows to the sky. Five days before, they clipped to a rope a string of broken souls. Now they would return to the war, but this time, resurrected in strength and love and invincible hope.

Produced by Oriana Zill de Granados and Michael Rey. Associate producer, Jaime Woods. Broadcast associate, Michelle Karim. Edited by Robert Zimet.