"The beating was brutal. Abuse was very bad": Freed Ukrainian POWs describe life in Russian captivity

One atrocity in Vladimir Putin's unprovoked war in Ukraine is largely hidden-- the torture of prisoners. We met three former POWs, survivors, last March in Kyiv, Ukraine's capital. They were soldiers, and all women. What they have to say is difficult but it further exposes the cruelty of Russia's invasion. Their stories can't be verified independently, but they track with testimony the U.N. collected from more than 150 former prisoners. At the end of a vicious battle last year in April, fear of Russian captivity was so great, that one of the women we met simply looked to God and said, "please let me die."

They fought in the southern port city of Mariupol. Once alive with 400,000 residents, Putin shelled Mariupol to misery. In April, the last Ukrainian troops were cornered in steel mills above the graveyard.

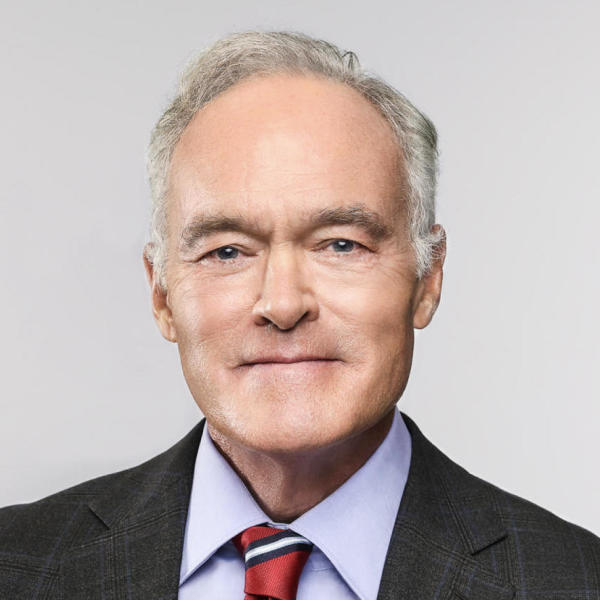

Scott Pelley: Tell me about the fight at the steel plant.

35-year-old Sergeant Iryna Stogniy is a medic.

Iryna Stogniy (translation): We saw people dying, children dying, children's heads being blown off… civilians… it's hard to bring those memories back…

Hard, because at least 25,000 civilians were killed.

Iryna Stogniy (translation): We tried to help civilians. We tried to give them some assistance, at least something – water, medicine, food there were little children with us. It's hard to watch your friend's head be blown off in front of you... It was… you can't describe this with words, difficult, very difficult when people you know, and children, die for nothing.

Sergeant Stogniy served in Mariupol with Captain Mariana Mamonova, a 31-year-old military doctor.

Mariana Mamonova (translation): There was one time when we saw a family running as we were driving to save our soldiers and when we were coming back, the father was crying over his family –[the] bodies of the mom and a little child.

Also at the steel mill, 33-year-old Sergeant Anastasia Chornenka ran communications.

Scott Pelley: The fight there was desperate.

Anastasia Chornenka (translation): Yes, constant aviation, artillery. This was non-stop fighting, non-stop shelling.

During the battle, Chornenka often sent her family a text, just one character.

Anastasia Chornenka (translation): It was very quick. If you [sent] a "plus" [sign] it meant you were alive.

Dr. Mamonova also had a message. It should have been for her husband back home. But she would not send it.

Scott Pelley: When did you realize that you were pregnant?

Mariana Mamonova (translation): I realized that I was pregnant in the middle of March. And when I saw that the test result was positive, I cried. I was hysterical.

But she didn't want her husband to know how much he stood to lose.

Mariana Mamonova (translation): I knew, if I died, it would be easier for him to reconcile with the loss of a wife than the loss of a wife and a baby.

By April, the fight for Mariupol was hopeless. Sergeant Stogniy's unit was surrounded.

Iryna Stogniy (translation): They took away our men separately, splitting them up, some of the men were beaten, some of our men were… how shall I put it… shot in the head…

Scott Pelley: The Russians killed unarmed men?

Iryna Stogniy (translation): Yes, we were unarmed.

About the same time, Captain Mamonova's unit was moving in the night to reinforce troops fighting for their lives.

Mariana Mamonova (translation): I would [just] say to my soldiers in my medical unit that if I was going to be captured – "just shoot me." "Don't look at me – just shoot me." And don't let me be captive. Don't let me.

Suddenly, in our interview, she was back, hiding in the rear of a truck that ran into a Russian patrol. She turned to a fellow soldier.

Mariana Mamonova (translation): Please tell me that we did not get captured. And he's looking at me, not knowing what to say. I see fear in his eyes. I realized that he can't tell me that we didn't get captured because we did get captured.

Next, came a blinding light and voices warning that they would be shot.

Mariana Mamonova (translation): [Artillery shells] were falling down. [And] at that moment I was asking God to let me die. I thought, "Oh, God, I don't want to [be captured]. I just want to die here. Please let me die."

She knew that the walls of Putin's prisons muffle cries of torture. A U.N. POW investigation collected testimony of executions, starvation, attacks by dogs, twisting joints until they break and mock executions.

Anastasia Chornenka (translation): When they first [talked] about taking me for execution, I only had enough time to pray and say goodbye to my children. Probably, the worst you feel is that you won't see your children ever again.

All her children knew was that the plus sign text stopped lighting up the phone.

Anastasia Chornenka (translation): You don't know where the fighting is and whether your children are in a safe place. This is the most frightening thing for a mother.

After Putin's unprovoked invasion, the U.N. POW report also found Russians abused by Ukraine mostly during capture. But Ukraine has opened its POW camp to international inspection while Russia hides its penal colonies. Iryna Stogniy says that she was moved among four Russian prisons and tortured with electricity.

Iryna Stogniy (translation): They would rape some men. When we were in Taganrog [prison] there was a cell for men and a cell for women. And we could hear our men screaming when they were being raped. They were making our men scrape off their tattoos. They were beating them badly. They did the same to women – they would beat them, pour boiling water on them. The only thing they didn't do - they didn't rape women. But the beating was brutal, abuse was very bad.

This is a Russian propaganda film, in April, that shows Mariana Mamonova in captivity. She's about four months pregnant and was told, privately, what would become of her baby.

Mariana Mamonova (translation): [They said] they would take my child away from me and they would move the [baby] repeatedly from one orphanage to another so I could never find my child.

Scott Pelley: I wonder, as you felt your daughter moving, what did you tell her?

Mariana Mamonova (translation): I was saying to my child that we were strong, and we could do it. "Your mommy is strong. Your mommy is military. Your mommy is a doctor. Your mommy will save you."

She asked only one thing from her child in return.

Mariana Mamonova (translation): You will be born in Ukraine. Can you hear me in there? You must be born in a free Ukraine.

Unknown to the prisoners, a free Ukraine was working to get them home. Andriy Yermak is chief of staff to President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

Andriy Yermak (translation): From the very first day, [President] Zelenskyy set up [the job] to return prisoners of war.

Leading negotiations for prisoner exchanges is Yermak's job. So far, his team has negotiated 46 POW swaps--trades of about equal numbers. 2,500 Ukrainians have been freed. An estimated 4,000 or so remain.

Scott Pelley: What is your commitment to Ukrainian POWs who are still being held by Russia?

Andriy Yermak (translation): [They should] hold on and remember that your country will never forget you. We will do everything to get you released. Have strength and faith in our ability to return everyone home.

There was fresh faith in his work in October with a deal to free 108 Ukrainians at once--all of them women. Iryna Stogniy was among them -- hooded, tied, and told nothing.

Iryna Stogniy (translation): We had been transported in vehicles and by plane so many times before, we thought they were just taking us to another cell.

Anastasia Chornenka was also in the dark. She had duct tape over her eyes so, her first inkling was something she could feel.

Anastasia Chornenka (translation): They put us on quite comfortable buses which were never used [and we thought] something's not right. Something's up because the bus felt comfortable and soft.

Later, the tape was cut from her eyes.

Anastasia Chornenka (translation): And you realize that there is no guard behind you, and you stand there (looking at) the big sign that reads "Ukraine."

Scott Pelley: I understand that you got a new tattoo after you were released? May I see it?

Iryna Stogniy (translation): It reads, "They were trying to kill me, they captured me, but I did not give in because I was born Ukrainian."

Another Ukrainian birth was delayed just enough. This is Dr. Mariana Mamonova walking to freedom. She told us near the end of her captivity, one kind Russian officer sent her to a hospital. And weeks later she was in a prisoner exchange.

Scott Pelley: How long was it from that moment of liberation until your daughter was born?

Mariana Mamonova (translation): Four days. I was liberated on the 21st of September and my child was born on the 25th.

A healthy girl named Anna.

Scott Pelley: So, she did exactly what you asked her to do - not be born until you were out of there.

Mariana Mamonova (translation): Yes. I was stroking my bump and I said: "OK, we are home now, and you can be born. Everything is good, we are home.

No one knows freedom like those who have lost it. The women we spoke to were held six months. Anastasia Chornenka retired from the military. Sergeant Iryna Stogniy is on duty near the front. And Captain Mariana Mamonova has maternity leave before she returns to the fight for Ukrainian freedom--and now--freedom's future.

Produced by Maria Gavrilovic. Associate producer, Alex Ortiz. Broadcast associate, Michelle Karim. Edited by Michael Mongulla.