Multinational effort working to save kids with cancer in Ukraine

Half the people of Ukraine are without power as low temperatures drop into the 20s. Russia is attacking civilian utilities with new waves of missiles in relentless assaults that the United Nations calls war crimes.

Even before Russia's invasion last February, more than a thousand Ukrainian children were already at war -- they were fighting cancer. Russian attacks on hospitals put these fragile children in immediate danger. The first lady of Ukraine asked the world for help and a renowned American hospital and 21 countries answered the call. What followed was an improvised flight to safety that Ukraine called the convoy of life.

The joy in 2-year-old Melania defied both cancer and war. But if she was to live, her family had to escape Ukraine. In February, her mother, Roksolana Semeraz joined the jam of thousands of refugees struggling to cross into Poland.

Roksolana Semeraz (Ukrainian translation): People were walking for [miles], leaving their cars and belongings behind. They would only take with them their most precious ones – their children, and pets. My heart was tearing apart.

At the border, Roksolana's desperation rose with the temperature of Melania's cancer drug she was carrying. It had to be refrigerated. But now they were trapped.

Roksolana Semeraz (Ukrainian translation): After waiting in line at the border for over 24 hours – and it would get warmer during the day – I had no storage for the medication, and that's when I would become desperate. I didn't know what to do -- how to [have] hope for the treatment of my child.

Mothers across Ukraine were losing hope for their sick children. This was the scene in the capital, Kyiv outside the window of Ohmatdyt Children's Hospital. Dr. Lesia Lysytsia told us, as the missiles flew, she rushed patients to the basement—many on chemotherapy.

Dr. Lesia Lysytsia (Ukrainian translation): All of the patients were very sick. Being moved to the basement definitely didn't do any good to their health.

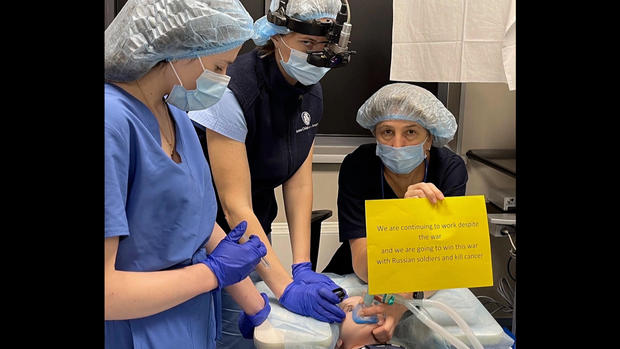

Dr. Lysytsia specializes in eye cancer. And in the treatment room they displayed their rage. "We are continuing to work despite the war and we are going to win this war with Russian soldiers and kill cancer." Maybe they didn't need the sign. Dr. Lysytsia's look said it all.

Dr. Lesia Lysytsia (Ukrainian translation): Their lives depend on the hospital's supplies, such basic supplies as blood, for example. You can't delay an operation for an oncology patient for a week or two. You can't stop their treatment because timing is crucial. If you delay chemotherapy for two weeks, then you've lost some percentage of their chance to survive.

The plight of desperate children touched the first lady of Ukraine, Olena Zelenska. We met in Kyiv in September. Elegant, but weary, she seemed to bear the burden of 44 million Ukrainians. Kids with cancer were among the first to find her empathy.

Scott Pelley: How did you work with other countries to evacuate these cancer patients?

Olena Zelenska (Ukrainian translation): On my level, I can speak with the first ladies. For this convoy to work, they needed to set up the system in their countries, making sure that physicians and hospitals in their country would accept the children for treatment.

Jill Biden responded for the United States, Brigitte Macron for France, Agata Kornhauser-Duda for Poland and many others. They helped activate charities and medical societies.

Olena Zelenska (Ukrainian translation): We had a big team, everyone helping each other, and I am very grateful for that.

That team likely saved the life of 17-year-old Zhasmin Alkadi-- a woman who impressed us with the creativity, personality and love of life that are rich in those who know they can lose them.

In February, doctors ordered her into chemotherapy to save her leg from bone cancer. But before that happened, Russia invaded. In March, Zhasmin joined the convoy of life. Patients throughout Ukraine took busses and trains to a children's hospital in Lviv near Poland. After treatment there, the children and their families crossed the border where they boarded a medical train. The entire route could take days or weeks. But throughout the exhausting journey, at least Zhasmin had her mother to lean on.

Scott Pelley: When we see you on the train, you are moving into the unknown in that moment.

Zhasmin Alkadi (Ukrainian translation): Yes. On that journey we didn't know what country on the destination list we would end up in. You're on the train hoping for the best, trusting doctors, hoping it will all be fine. But, as you said, you're moving into the unknown. Where will I be tomorrow?

The answer turned out to be this improvised triage center in Poland set up by an American hospital, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital of Memphis, Tennessee—named for the patron saint of hopeless causes.

Dr. Marta Salek: There are patients who are more likely to get sick than others, and so we want to identify those patients so we can pay attention when they get here.

That's Dr. Marta Salek of St. Jude, who helped organize the triage center in an empty hotel in the polish countryside.

Dr. Marta Salek: The children would get escorted from Lviv to the border so that they didn't have to wait in line. And then, they would cross the border into Poland. The children who were sick would go straight to the hospital with an ambulance, sometimes a helicopter. The ones that were stable would take this really impressive medical train that had medical staff. They had an ICU and a surgical theater. And they would take this train to a city called Kielce that was close to where our Unicorn Clinic was.

The 'Unicorn Clinic' was the name they gave to the hotel that could hold 300 refugees--patients and their families. Medical records were translated and hospitals found for treatment, at no charge, in 21 welcoming countries.

Scott Pelley: I suspect you'd never heard of Memphis, Tennessee?

Zhasmin Alkadi (Ukrainian translation): I just knew there was such a place, but not much else.

In March, Zhasmin Alkadi arrived in Memphis for treatment at St. Jude.

Scott Pelley: What are the doctors telling you now?

Zhasmin Alkadi (Ukrainian translation): I have a few rounds of chemotherapy left. Everything is going well. I already had my leg amputated, unfortunately. The doctors said it was too late to save the leg and it was impossible. I just need to finish my chemotherapy and I can then continue living my life, as before.

Also living a rambunctious life at St. Jude, is 2-year-old Melania Semeraz, the girl who had been stuck at the Polish border with her refrigerated medication. Her mother, Roksolana, told us there's hope that Melania can be cured of her fibrosarcoma—a cancer of the connective tissue in her leg.

Roksolana Semeraz (Ukrainian translation): We fled the war, from people who just wanted to kill and [here] people are greeting you and want to give you the best help. They did so much for us and are still doing. This is something incredible.

Scott Pelley: What does the world need to know about this war?

Roksolana Semeraz (Ukrainian translation): It is scary that in our century people still believe that war is worth something. There are so many real problems in the world, such as cancer. Why doesn't Russia fight cancer?

But rather than fight disease, Russia is attacking medicine. The U.N. says Russia has assaulted hospitals and clinics 630 times. This is a hospital in Mykolaiv, a hospital in Mariupol. The Luhansk Children's Hospital and a maternity hospital in Kyiv.

Scott Pelley: What are the Russians trying to do?

Olena Zelenska (Ukrainian translation): They are waging war against civilians. They're trying to scare people away, make them flee, leaving empty cities and villages behind, and then they would come and seize these [lands] using scorched-earth tactics.

Since our visit with Mrs. Zelenska, Russia has devastated Ukraine's power grid. The Kyiv Children's Hospital we visited sent us images of surgeries illuminated by generators and the neonatal intensive care unit swaddled in sandbags. Dr. Lesia Lysytsia remains at work.

Scott Pelley: What has the war taken from Ukrainian children?

Dr. Lesia Lysytsia (Ukrainian translation): Childhood, the most valuable thing that children have. They stole childhood from our children, and we now have a lot of [kids] who are mentally broken, no matter how hard we try to rebuild their lives.

The mass evacuation of children with cancer ran, last spring, from March through May. Dr. Marta Salek of St. Jude told us a few children did not survive the journey.

Dr. Marta Salek: And so, there were some instances where children would die on the journey. But I think those children would have died if they had stayed in Ukraine. It was the gift that we could give to the families to give them that hope that the child could die peacefully, in a safe environment, and not have to worry at the effects of war.

Scott Pelley: A gift?

Dr. Marta Salek: Yeah.

Scott Pelley: What do you mean?

Dr. Marta Salek: I can't imagine being a parent who has a child that with a chronic condition that is approaching end of life, and the family member has to worry, "Will the hospital be struck by a missile?" At the time the decision was to evacuate those children with the risk that they might die enroute. But if that would bring peace to the family, as they were going through this terrible circumstance that was also now affected by war, then it felt like the right thing to do at the time.

Scott Pelley: Providing these children with a safe place to die?

Dr. Marta Salek: Yeah. It's really important. And so, we honored that request.

By recent count, the convoy of life evacuated 1,119 children into a welcoming world—allowing their families to fight one war at a time.

Scott Pelley: I wonder what you would like to say to the Americans who have welcomed your family?

Roksolana Semeraz (Ukrainian translation): Wherever I go, I want to say thank you to every person that I meet. I feel like I want to scream out loud to everyone: "Thank you!" America gave this to us. And I would like to have a [chance] to help others too, so that people believe that kindness wins... we need to do more good things.

Produced by Nicole Young and Kristin Steve. Broadcast associates, Michelle Karim and Matthew Riley. Edited by Jorge J. García.