Uber drivers use armed security in South Africa

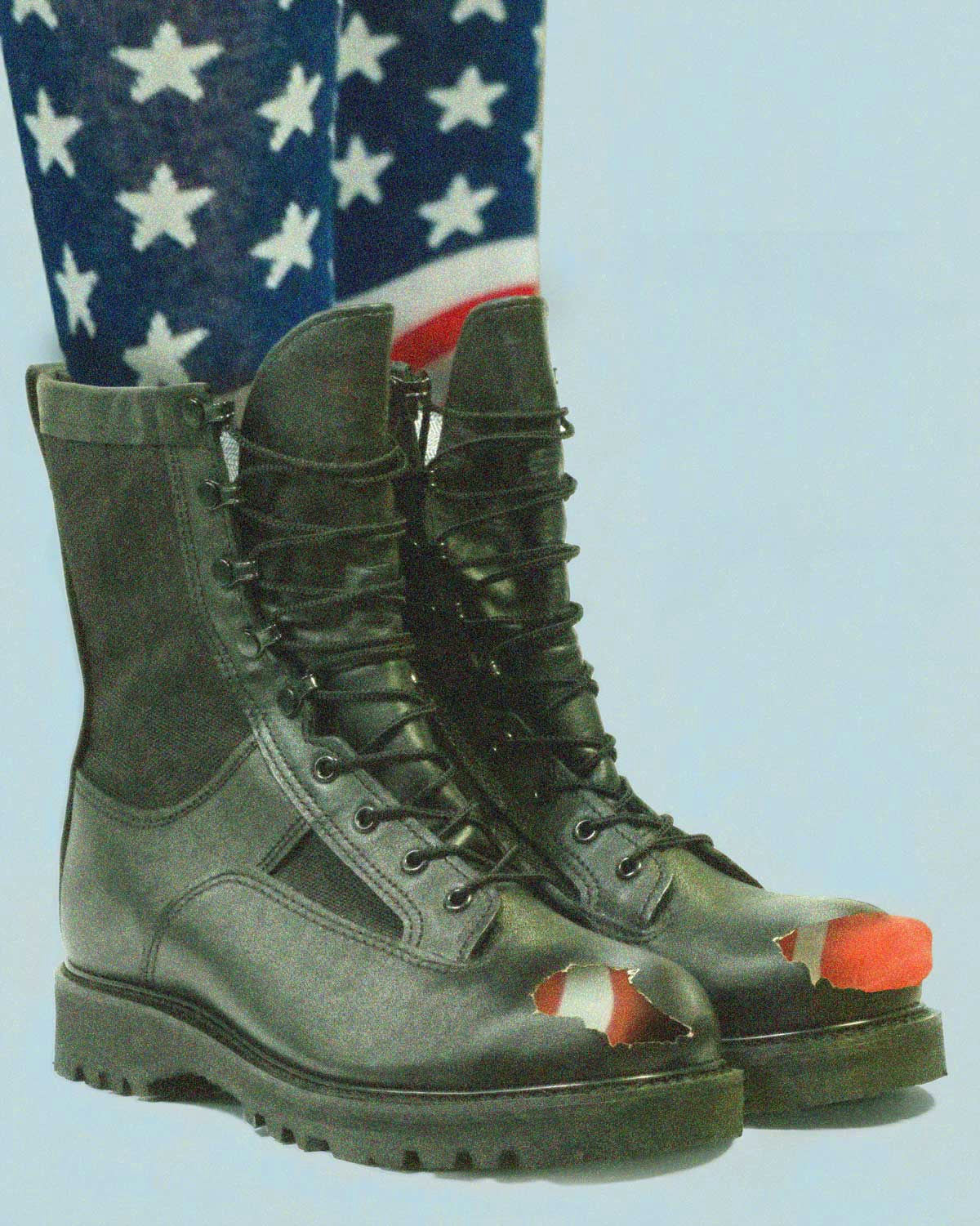

On an average day outside Johannesburg's downtown train station, a handful of men in all-black military gear are positioned down the block. They wear bulletproof vests, combat boots and wool beanies. A patch on their sleeves reads, "Hi-Risk Security Company, Rapid Response Unit."

As we exited the train station during a trip to South Africa last month, one of the men approached us. "Are you looking for an Uber?"

Meet the private security force working for the ride-hailing company in Johannesburg.

"On this corner, you are perfectly safe," the guard told us.

We had only his word for it because clashes between Uber and local taxi drivers, known as "metered taxis," are now a common occurrence in Johannesburg and surrounding cities. To put it bluntly, being an Uber driver here is dangerous.

In the last year, the violence has included reports of Uber drivers being beaten as they drop off passengers at busy areas with taxi stands, like train stations. One Uber driver, whose car was set on fire after an attack in June, died two weeks ago from severe burns.

"There is no excuse for the violent acts described," Uber wrote in a June 12 blog post after the attack. "We know that these actions do not represent the entire industry, however, this violence and intimidation against those who choose to use the Uber app must stop."

Turmoil between taxi and Uber drivers isn't isolated to South Africa. Protests, beatings and attacks have been reported in New York, London, Paris and Mexico City because taxi drivers are upset that Uber, one of the world's largest ride-hailing services with operations in 76 countries, is taking their customers. Incidents have also reportedly occurred across the African continent -- from Egypt to Kenya to Nigeria. But the problem appears to be worth it for Uber. Africa has a booming population of more than 1.2 billion, all potential customers.

"Nations like India, China and the whole African region are potentially ripe for this type of mobility," said Susan Shaheen, co-director of the Transportation Sustainability Research Center at the University of California, Berkeley, "given the population density, given the infrastructure and given access to smartphone technology."

Uber didn't respond to multiple requests for comment on this story.

"Bricks, knives, whatever"

Driving for Uber in South Africa can be lethal.

David Bhili, 42, is a full-time Uber driver in Johannesburg and said the job is great because there's no boss, but "they're those things that need to be fixed." He was talking about the violence by taxi drivers.

"They have knobkerrie, bricks, knives, whatever," Bhili, who had graying hair and a trim mustache, said. "After they finish, they even burn the car into ashes. They can also use guns."

When we asked Bhili what a knobkerrie was, he made a fist with his hand and said, "It's like a stick, but at the front it's like this at which you can hit someone on the head." Turns out the knobkerrie is a traditional hunting weapon used in South Africa.

When Uber drivers are directed to drop off passengers at busy train stations, the taxi drivers are waiting and look prepared to fight, Bhili said.

Another full-time Johannesburg Uber driver, Eric Vukani, 33, said he's also seen menacing-looking taxi drivers waiting at train stations. Like Bhili, he's never had an incident but that's because he's always on the ready.

"You cannot even talk to them," Vukani said. "If I see a situation with people approaching me, I drive away fast. [If] you wait for them, you know you get into trouble."

To deal with the violence, Uber amped up safety measures in South Africa over the last year. Several drivers told us the Hi-Risk guards are armed, though the guards we saw didn't have weapons readily visible. When we asked one guard if he was armed, he said he wasn't allowed to disclose that information.

Hi-Risk confirmed via email that it's working for Uber to protect drivers and passengers around South Africa, but because of a non-disclosure agreement it signed with the company, it couldn't provide further information.

Besides hiring the security force to patrol the most dangerous drop-off spots, Uber also provided drivers with an emergency hotline to call if they feel unsafe. And the company is working with multiple response services able to dispatch security and medical teams in emergency situations.

Uber set up a donation platform for the driver who was killed after his car was set on fire last month, according to a driver in Johannesburg. The platform let South African Uber drivers donate directly to the victim's family. They entered the amount they wanted to give and were told the donation would be automatically deducted from their pay statements. Uber reportedly matched those donations. The window for contributing ended on Friday.

To evade violent confrontations, Uber drivers in South Africa try to keep a low profile. In the US, Uber cars are identified with a large company logo on the front or rear window. But in South Africa, Uber cars don't carry such branding. That's because drivers there said having an Uber sticker would just make things worse. "It's better this way," Bhili said.

Still, taxi drivers can usually recognize Uber cars because they tend to be newer and smaller, with a smartphone on the dashboard.

Similar violence has plagued drivers in Kenya, but Stephen Tanui, a 27-year-old Uber driver we spoke with in Nairobi, said attacks from taxi drivers have dropped off recently. Instead, the big problem is violence from thieves. He's heard stories of Uber drivers dropping off passengers in dangerous neighborhoods. Then thieves descend on the car, pull the driver out and lock them in the trunk.

"They basically kidnap you," Tanui said. "They drive you to the bush, then rob you."

He also won't go to certain neighborhoods after 10 p.m. For fear of being attacked.

"Apartheid," again

Still, throughout Africa, the tension between taxi and Uber drivers isn't likely to go away anytime soon. Taxi drivers say the main issue isn't violence, it's jobs.

Sipiso Zulu has been a metered taxi driver since 1994. He's not upset with Uber drivers -- he's upset with Uber. Zulu said poor people can't afford to become Uber drivers because the upfront costs are too high. Uber requires South African drivers to use vehicles from 2013 or newer, and the cars must have a working radio, air conditioning and four doors. Zulu said even if he wanted to, he couldn't afford the monthly payment of 6,000 Rand ($460) to own a car like that.

Metered taxi drivers can make anywhere between 1,400 Rand to 10,000 Rand ($105 to $750) per month, whereas Uber drivers can make between 2,500 Rand and 15,000 Rand ($200 to $1,100) per month.

"How people going to buy a car?" Zulu said.

On top of that, Uber's rates are roughly a third lower than taxis, which is a common tactic Uber uses when entering new markets. By undercutting their rates, taxi drivers say Uber steals their passengers. A ride that costs about 150 Rand ($11) in a taxi is roughly 100 Rand ($7) in an Uber.

In its blog post last month, Uber said it has no intention of swiping passengers from taxis.

"We are not interested in taking away anyone's business," Uber wrote. "There is plenty of opportunity for everyone. We have also made it known that we welcome anyone who wants to use the Uber app."

But for Zulu, it's hard to see that opportunity.

"White people don't take taxi now. It's Uber," he said. "Apartheid was finished and now it's starting again."