New York City puts cap on Uber, other ride-hailing services

New York City is hitting the brakes on fast-expanding ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft. Lawmakers on Wednesday approved a proposal to freeze new licenses for car services for one year, becoming the first large city in the U.S. to impose such restrictions.

The city council also approved proposals to set minimum pay levels for all drivers and minimum fares, which are now regulated for traditional cabs but not their multitudes of new competitors.

"Our city is directly confronting a crisis that is driving working New Yorkers into poverty and our streets into gridlock," New York Mayor Bill de Blasio said in a tweet, saying he would sign the bills into law. "The unchecked growth of app-based for-hire vehicle companies has demanded action – and now we have it."

Joseph Okpaku, vice president of public policy at Lyft, criticized the city council's decision.

"These sweeping cuts to transportation will bring New Yorkers back to an era of struggling to get a ride, particularly for communities of color and in the outer boroughs," he said in a statement following the vote. "We will never stop working to ensure New Yorkers have access to reliable and affordable transportation in every borough."

In a statement to CBS News, Uber said the decision will "threaten one of the few reliable transportation options while doing nothing to fix the subways or ease congestion."

The company said it will continue to work with New York City government and state leaders for solutions to keep up with the growing demand, such as congestion pricing.

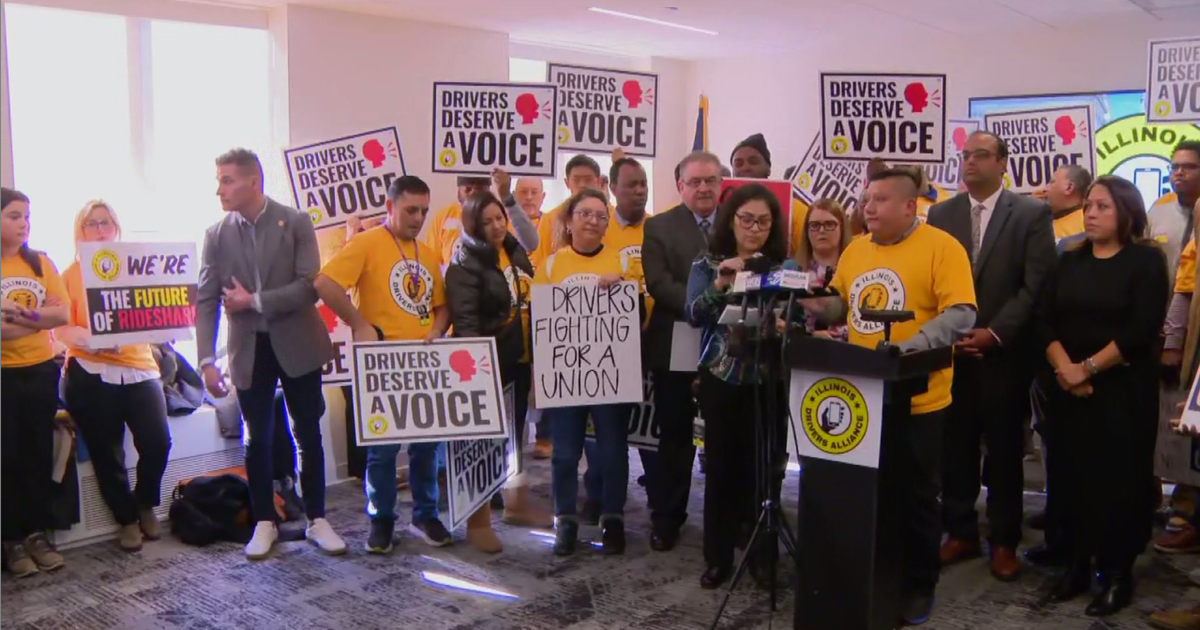

The New York Taxi Workers Alliance, which has pushed hard for the freeze, hailed the city council.

"This victory belongs to yellow cab, green cab, livery, black car, Uber and Lyft drivers who united together in our union to transform our shared struggle and heartbreak into hope and strength," Bhairavi Desai, executive director of the NYTWA, said in a statement. "And this victory belongs to New Yorkers and our allies who have stood with us to say, not one more death, not one more fallen driver crushed by poverty and despair."

Six New York taxi drivers have committed suicide this year amid difficulty of earning a living, according to the group.

Leading up to the vote, City Council Speaker Corey Johnson said lawmakers aren't against the ride-hailing newcomers. "We think they've actually filled a need," he said. But he said better regulation is needed.

For generations, taxi drivers in New York were protected by rules restricting competition. Around 13,500 yellow cabs had the special licenses, called medallions, needed to pick up passengers on the street. Several thousand more drivers worked for black car companies that dispatched vehicles by phone, mostly in the outer boroughs of Bronx, Queens, Staten Island and Brooklyn, where yellow cabs generally wouldn't travel.

That system was smashed when the city began allowing passengers to use smartphone apps to hail cars almost anywhere.

The change kicked off a dizzying increase in the number of car service drivers from about 65,000 in 2015 to 100,000 today.

One unforeseen development has been the plunging value of the traditional taxi medallions. As recently as four years ago, they were changing hands at prices reaching $1 million. They were considered such a ticket to guaranteed income, banks allowed owners to borrow huge sums against them for home mortgages or school loans.

Now, many of those loans are coming due. Drivers no longer have the income to pay them off. And with medallions now trading at $200,000 or less, owners don't have the collateral to refinance.

Driver Lal Singh said he owes $312,000 on a medallion he thought would be his ticket to middle-class comfort. But he can't sell at a price high enough to cover his debt. So at age 62, he's still driving 14-hour shifts, despite having high blood pressure and diabetes, with every penny going to pay off his debt.

"Everybody say, 'This is my retirement. Some income will come in from the medallion. We will survive,'" he said. "But now we have no hope and I don't see any place, which direction I should go."

Six drivers have killed themselves in the last year, including one who shot himself in his car in front of City Hall after railing against politicians and Uber in a newsletter column.

"I will not be a slave working for chump change," Douglas Shifter wrote. "I would rather be dead."

Drivers previously pushed for a cap on new competition in 2015, but were beaten back by ride-hailing companies. The same companies are now pushing back on the new proposals, including telling users through social media and on their apps that the legislation could make rides more scarce and more expensive.

"We're really concerned about the process and the speed with which the council is trying to ram this through," said Joseph Okpaku, vice president of public policy at Lyft.

Uber spokesman Josh Gold said a cap on new licenses would reverse the progress made extending service to neighborhoods poorly served by traditional taxis.

That argument has gotten support from some civil rights activists like the Rev. Al Sharpton, who have long criticized the yellow cab industry for discrimination and profiling of minorities.

"They're talking about putting a cap on Uber, do you know how difficult it is for black people to get a yellow cab in New York City?" Sharpton wrote on Twitter.

The industry hasn't seen this level of upheaval since the first half of the 20th century, when the medallion system was put in place to deal with issues of competition, said Graham Hodges, a professor at Colgate University.

Flaws in that system, like racial profiling and inadequate demand, "made it easy for Uber, Lyft and the others to come in, say, 'We're going to provide a much better service,'" he said. "That doesn't mean those flaws couldn't be remedied without destroying the system," he added.