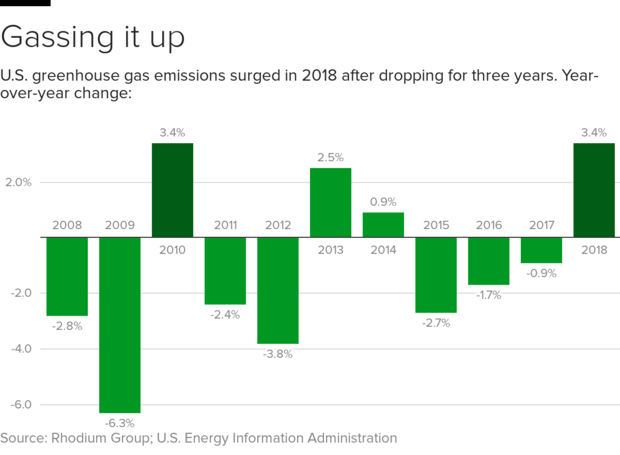

U.S. carbon emissions jumped in 2018 despite record coal plant closings

After dropping for three years in a row, U.S. carbon emissions spiked in 2018, demonstrating how hard it can be to move away from fossil fuels while the economy is growing.

Preliminary data from the Rhodium Group, a research consultancy, found that emissions rose 3.4 percent last year. That's even as Americans' reliance on coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel, hit a 40-year low.

"While a record number of coal-fired power plants were retired last year, natural gas not only beat out renewables to [replace] most of this lost generation but also fed most of the growth in electricity demand," the report said.

Natural gas, which has become a cheap and attractive competitor to coal, is cleaner-burning, but it is still a fossil fuel, emitting about half the carbon dioxide that coal does. Earlier studies have found that switching over all the world's coal plants to natural gas would do little to curb climate change.

The Trump administration's rollback of environmental laws and decision to withdraw from the Paris climate accords play a role in the increase. But the main culprit is last year's spike in economic growth. Between 2007 and 2015, U.S. emissions came down 12 percent as utilities brought on clean-energy technology and the Great Recession dampened demand for power. In 2016 and 2017, emissions still decreased, but more slowly. Last year, as the economy expanded at the fastest pace in 15 years, boosted by tax cuts and other measures, emissions also grew at a record-setting pace.

"So long as the economy is growing, that dynamic isn't going to change without a lot of breakthrough technology innovations or federal policy actions," John Larsen, one of the report's authors, told Greentech Media.

The transportation sector was the largest source of carbon emissions last year, with a slight drop in gasoline demand more than offset by increased trucking and air travel. Transport-sector emissions grew 1 percent last year, the same as 2017, according to Rhodium. In this sector, increases in efficiency—doing more with less power—and a move toward electric transport is beginning to make a dent, although a small one.

The largest emissions growth was in sectors that don't get much attention outside climate policy circles: Industry and buildings. The industrial sector added 55 million metric tons of carbon last year, more than four times its annual average in the past decade, because of an uptick in industrial activity. The sector is predicted to grow its "gassiness" and to become the leading carbon emitter in Texas within three years, according to Rhodium.

"Absent a significant change in policy or a major technological breakthrough we expect the industrial sector to become an increasingly large share of US greenhouse gas emission in the years ahead," the report found.

Emissions from buildings increased by 54 million tons last year, a sevenfold increase from its typical rate of increase. That's partly because of weather, with a colder winter requiring more heating, but Rhodium expects population growth to keep driving emissions in this sector.

The prospect of reducing emissions by up to 28 percent from their 2005 levels—as the U.S. would be required to do under the Paris climate agreement—will require a radical shift. It would mean cutting emissions at nearly double the pace of their 2007-to-2015 decline. That prospect, while not impossible, would require an immediate policy shift or a technological breakthrough, Rhodium found.

"The U.S. was already off track in meeting its Paris Agreement targets. The gap is even wider headed into 2019," it said.