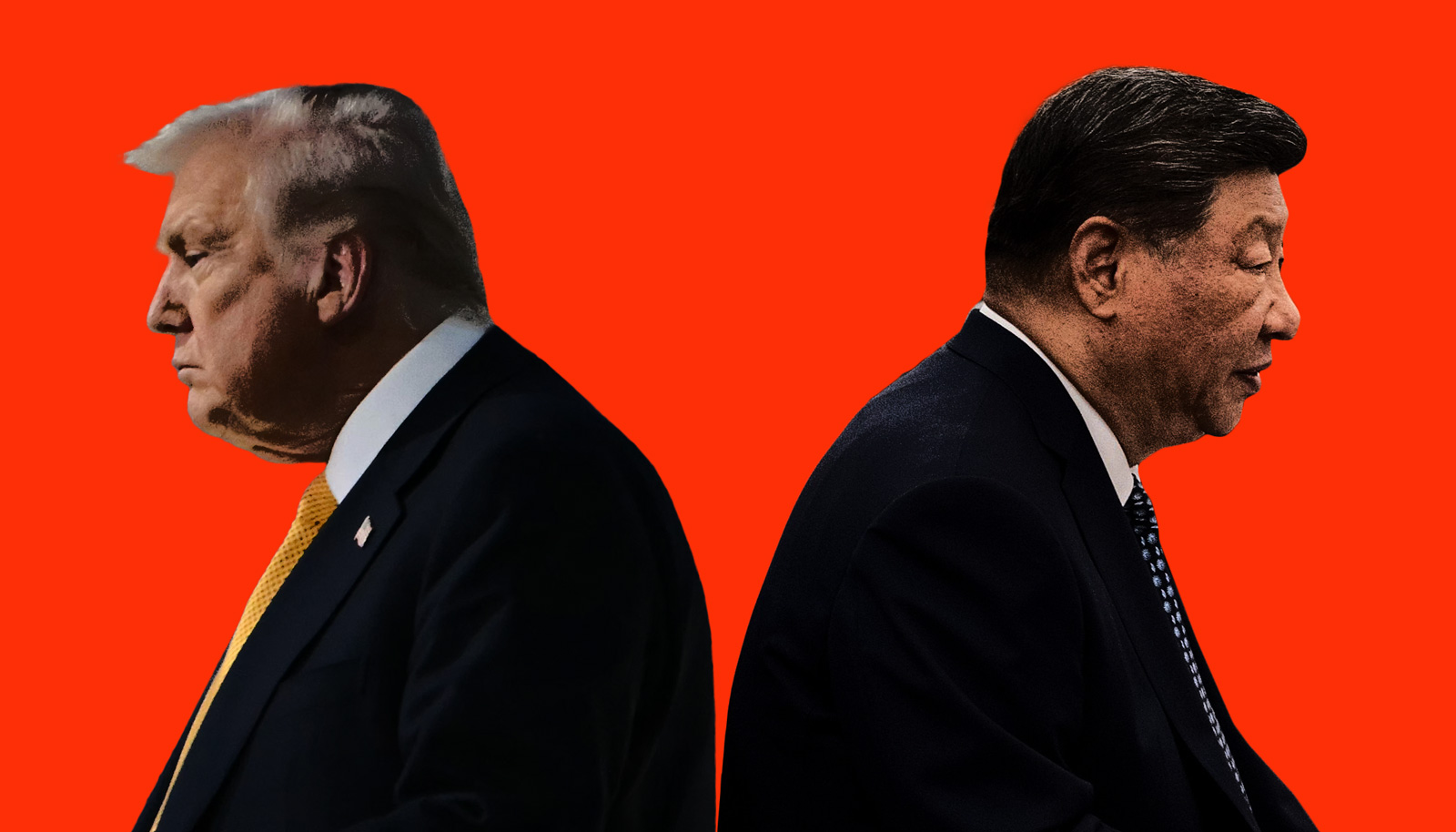

U.S. businesses want help with China, not a trade war

BEIJING/WASHINGTON - Although worried about the prospect of a trade war, American businesses operating in China nonetheless want President Donald Trump to wring some

concessions on market access from China’s leader Xi Jingping when the two meet this week.

Mr. Trump warned in a tweet last week the meetings at his Mar-a-Lago resort on Thursday and Friday will be “very difficult” and “American companies must be prepared to look at other alternatives.”

The president has said he wants U.S. companies to stop investing in China and instead create jobs at home. He has also accused China of manipulating its currency to boost exports.

Critics within U.S. industry have accused China of unfair government subsidies to its companies and of flooding the U.S. market with cheap products from steel to solar panels, while restricting foreign investment over vast swathes of the world’s second-biggest economy.

But they also worry Mr. Trump’s policies on China are not entirely clear, with his trade team still not in place, and may be subject to a “grand bargain” involving other issues such as North Korea.

Mr. Trump is set to enter the meeting without several key advisers, including his pick for trade negotiator, Robert Lighthizer, who has yet to be confirmed by Congress. His nominee as ambassador to China, Iowa Governor Terry Branstad, has also yet to be confirmed, while several posts in the U.S. State Department that formulate Asia policy remain unfilled.

“With this in mind, it is hard to imagine that there will be much in the way of concrete accomplishments at this summit, or even that there has been any significant interagency discussion on strategy leading up to it,” said Randal Phillips, Mintz Group’s Beijing-based managing partner for Asia and the former chief CIA representative in China.

Some of the largest U.S. companies have contributed to the billions of dollars of foreign direct investment that have poured into China over the past two decades, creating hundreds of thousands of jobs. They include tech companies like Apple (AAPL), which makes much of its iPhone in China, automakers such as General Motors (GM) and Ford (F), heavy machinery firms like Caterpillar (CAT), retailers like Starbucks (SBUX) and makers of shaving foam and detergent, like Procter & Gamble (PG).

U.S. steel producers want the president to press Xi on Chinese steel prices, according to a source who has been in discussions with the administration in advance of the summit.

U.S. automakers complain about a disparity in tariffs: The U.S. has a 2.5 percent tariff on auto imports, China’s is 25 percent.

But the stakes are perhaps highest for American technology firms, which worry that China’s new cybersecurity law taking effect in June, sets potentially discriminatory standards for multinationals.

The Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (ITIF), a think tank whose board includes representatives from Apple, IBM (IBM), Google (GOOG) and other tech heavyweights, has urged the Trump administration to pressure China to “stop rigging markets.” It warned that possible retaliation from Beijing was not a reason for inaction.

Trump has staked out various positions on China as president in his tweets, phone calls and statements.

In a phone call with Xi after taking office, Trump gave ground on one of Beijing’s most sensitive issues -- the status of Taiwan -- after earlier suggesting he might not stick to Washington’s long-held “one China” policy.

Mr. Trump signed two executive orders on trade on Friday, one to improve import tariff collection and another to study the causes of the U.S. trade deficit. He said at the White House signing ceremony he and Xi were “going to get down to some serious business” and vowed that “the theft of American prosperity” by foreign countries would end.

Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Zheng Zeguang said on Friday the U.S.-China trade imbalance was mostly the result of differences in the two countries’ economic structures and noted China had a trade deficit in services.

China tops the list of countries that have trade surpluses with the U.S., at $347 billion last year.

Some in the U.S. business community worry about tit-for-tat retaliation in trade disputes with China. Jacob Parker, vice president of China operations at the U.S.-China Business Council, said the two presidents need to take “positive actions that would lead to a more durable relationship, not retaliatory actions that would lead to a trade war.”

The list of commercial issues between the two countries was so long, it would be impossible to make a major dent in them with one meeting, he said.

China is the largest export market for U.S. soybean producers, accounting for 62 percent of U.S. soy exports in 2016 with a value of over $14 billion, leading some experts to suggest the sector could be particularly vulnerable to retaliation.

Steve Censky, chief executive of the American Soybean Association, told Reuters he hopes Mr. Trump will take a “prudent” approach to the trade relationship and address any issues in a

“workman-like manner,” recognizing that both countries have a lot to lose if the relationship suffers.

William Zarit, chairman of the American Chamber of Commerce in China, met senior Trump administration officials in February and said “it was clear they were very familiar with the issues

facing American companies in China, perhaps more so than previous administrations.”

But several corporate lobbyists, representing a range of companies, expressed concern that Mr. Trump’s lack of attention to detail could prove counterproductive when it comes to the intricacies of the massive trade and investment relationship.

“It’s not yet clear whether ... this is a White House that wants to fundamentally reset the terms of the relationship or tinker at the edges and declare a public relations win,” said a China expert at a Washington business lobby who asked not to be named.