White evangelical support for Trump goes beyond his policies, supporters and historians say

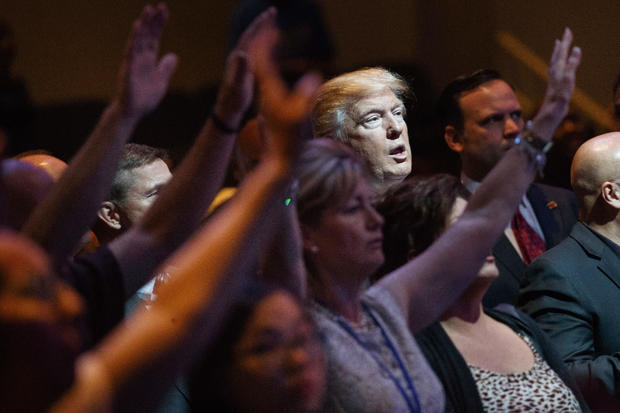

When Donald Trump powered his way to presidential victory in 2016, defying the expectations of many polling experts, it quickly became evident that White, self-identifying born-again or evangelical Christian voters were among the most crucial components of his winning coalition.

On its face, it was not a natural fit: Mr. Trump seldom addressed his personal faith before his candidacy, is twice-divorced and has faced over two dozen accusations of sexual misconduct. Some at the time found the political marriage to be one of convenience. But the evangelical attraction to his candidacy extends far beyond ideological alignment, historians and evangelical supporters of Mr. Trump told CBS News.

"There was much less tension between family values, evangelicalism and the support for Trump that we were seeing because of a long-standing commitment to a kind of rugged, patriarchal leadership, a kind of a militant masculinity," said Calvin University religious historian Kristin Kobes Du Mez. "For decades, evangelicalism has been writing and preaching that men needed to be strong, and that God made men to be strong, so that they could protect their families and their churches and their country. This was the kind of leader that they have been conditioned to look to."

White evangelical Christians, who made up more than a third of Mr. Trump's support, have reliably voted Republican for decades.

A number of influential voices are credited with channeling Christian religious ideology into a salient political movement. Among them were televangelist Jerry Falwell, who founded the Moral Majority, and James Dobson, who founded Focus on the Family, a conservative Christian organization and ministry, in 1977.

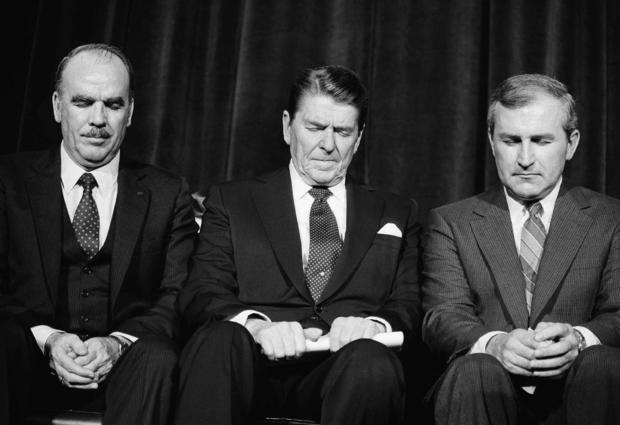

Experts point to the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980 as a seminal moment for American evangelicalism's influence on presidential politics. Reagan did not appear to be an obvious match for the religious right — he, too, had been divorced and was a coastal, entertainment industry veteran. His opponent, incumbent President Jimmy Carter, was a devout Southern Baptist Sunday school teacher. Yet Mr. Reagan was elected with an overwhelming two-thirds of the evangelical vote.

"They voted for Reagan, because Reagan promised them a 'shining city on a hill,' and he promised them the thing that they thought they were losing," said Richard Flory, the research director of USC's Center for Religion and Civic Culture.

Flory alludes to a pervading existential concern among many White evangelical Christians: a fear that their religious liberty is being infringed upon — that freedom of religion and freedom of worship are at risk.

"I think Christians have long been a group where people feel very comfortable minimizing them, and thinking how crazy it is that you have trust in God," Randy Baron, a self-identifying evangelical Christian from Holland, Michigan, told CBS News. "You're starting on a foot where people are going to minimize your opinions, say that you're uninformed or that you have a blind faith."

About one in four American adults identifies as an evangelical Protestant Christian; it is the most common religious affiliation in the country, according to Pew Research Center's 2014 Religious Landscape Survey.

Prominent evangelical leaders interviewed by CBS News describe a sense of frustration in the years preceding the 2016 election, particularly over the evolution of American public opinion toward more liberal views on hot-button issues like abortion and gay rights.

"Many of us in the faith community were very frustrated, because we had watched our rights be assaulted," said Georgia megachurch pastor Jentezen Franklin. "We just felt like if there ever was a time that we needed to speak up, and find a candidate that would include people of faith in their policy, it was in that year of 2016. We felt that our children and our children's children would not grow up in a free America that we had grown up in."

Those sentiments created a distinct opening for a candidate like Donald Trump, who readily shared his grievances about the state of the country.

"I think 'Make America Great Again' is broader than just an evangelical attitude," said Lauren Kerby, a religious literacy specialist at Harvard Divinity School. "But it is, in many ways, tailor-made for them — they hear that and they absolutely hear, 'We need to make America Christian, the way it used to be when it was run by White conservative Christians.'"

Mr. Trump's worldview aligned with the views of many on the religious right. For example, he frequently lamented his treatment by the media, dismissing coverage as biased or unfair. For many conservative evangelicals, "deep mistrust of the mainstream media long predates Trump," said religious historian Du Mez.

His brash nature on the campaign trail — often regarded as a political liability by pundits and traditional GOP figures — may have also factored into Mr. Trump's appeal for evangelicals.

"There's kind of a paradox in evangelical life," said Mark Galli, the former editor-in-chief of Christianity Today, who published an anti-Trump editorial in 2019. "On the one hand, they're very suspicious of human authority, because the Bible is the word of God, and that's the ultimate authority.

"On the other hand, the more conservative evangelical you are, the more you tend to get attracted to authoritarian figures," Galli continued. "That might be preachers, and often it's government leaders. So, Trump has that swagger — he has kind of a charisma for that group of people."

A review of dozens of Trump campaign appearances from 2016 shows remarkable consistency in his appeals to White evangelical voters.

He regularly warned rally attendees that "Christianity is under siege." He suggested there were forces "chipping away at Christianity," and accused Democrats of waging a war on Christmas. At a campaign stop in Sioux Center, Iowa, he promised supporters that "Christianity will have power. If I'm there, you're going to have plenty of power, you don't need anybody else."

In time, he accrued endorsements from prominent evangelical voices, including Franklin, the Georgia megachurch pastor; Dallas megachurch pastor Robert Jeffress; and then-Liberty University president Jerry Falwell, Jr.

"We weren't voting for him for his personal piety, but for his strong leadership," Jeffress told CBS News. Franklin echoed the thought: "He never pretended to be a super Christian," he said. "He never pretended to be some holy saint."

The fervor for Trump's candidacy among the religious right took some by surprise. A Pew Research Center analysis found 81% of White evangelical Christians voted for Mr. Trump in 2016, a greater share than George W. Bush in 2004, John McCain in 2008 or Mitt Romney in 2012.

"Reagan is the first president who allowed evangelicals to have a seat at the table — he didn't listen to them that much, but he at least allowed them a seat at the table," Jeffress said. "Neither of the Bushes even pretended. But Donald Trump is the first president who actually listened and incorporated some of the views of evangelicals in his policies."

Once in office, Mr. Trump made good on many of his promises to the evangelical voting bloc, including his nomination of "pro-life" judges to the Supreme Court.

While polling ahead of the 2020 election shows him trailing Democrat Joe Biden nationwide, his support among White evangelicals has remained nearly unchanged.

"When people talk about President Trump, I'd be hard pressed to find anything that would indicate that he has exhibited any fruits of the Spirit," Baron, the Michigan evangelical voter, said. "But what I will tell you is that he has been a friend to Christians, and he has followed through and done what he said he's going to do. And that's— that's pretty tough."