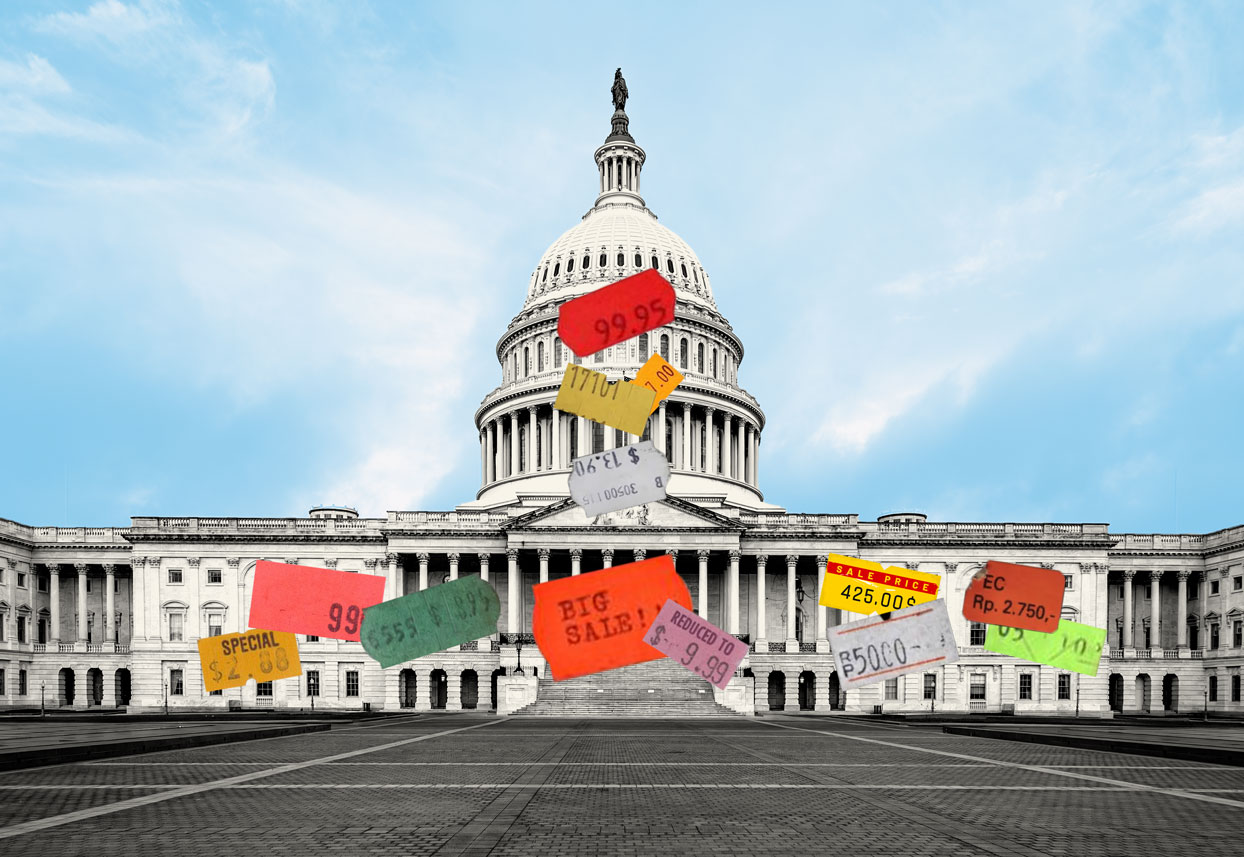

Trump vs. China on currency: What it’s all about

WASHINGTON - President-elect Donald Trump has vowed to name China a currency manipulator on his first day in the White House.

There’s only one problem -- it’s not true anymore. China, the world’s second-biggest economy behind the U.S., hasn’t been pushing down its currency to benefit Chinese exporters in years. And even if it were, the law targeting manipulators requires the U.S. spend a year negotiating a solution before it can retaliate.

Mr. Trump spent much of the campaign blaming China for America’s economic woes. And it’s true that the U.S.-China trade relationship is lopsided, with China selling a lot more to the U.S. than it buys. The resulting trade deficit in goods amounted to a staggering $289 billion through the first 10 months of 2016.

But in fact, for the past couple of years China has been intervening in markets to prop up its currency, the yuan, not push it lower.

It went a step further on Thursday, watering down the significance of the dollar and adding 11 additional currencies in a foreign-exchange basket, according to a document released by the China Foreign Exchange Trading System.

What does currency have to do with the trade gap?

When China’s yuan falls against the U.S. dollar, Chinese products become cheaper in the U.S. market and American products become more costly in China.

So the U.S. Treasury Department monitors China for signs it’s manipulating the yuan lower. Treasury has guidelines for putting countries on its currency blacklist. They must, for example, have spent the equivalent of 2 percent of their economic output over a year buying foreign currencies in an attempt to drive those currencies up and their own currencies down.

Treasury hasn’t declared China a currency manipulator since 1994.

What would happen if the U.S. declared China a currency manipulator?

Probably not much, at least initially.

If Treasury designates China a currency manipulator under a 2015 law, it’s supposed to spend a year trying to resolve the problem through negotiations.

Should those talks fail, the U.S. can take a number of small steps in retaliation, including stopping the U.S. Overseas Private Investment Corp., a government development agency, from financing any programs in China. Trouble is, the U.S. already suspended OPIC operations in China years ago -- to punish Beijing in the aftermath of the bloody 1989 crackdown in Tiananmen Square.

So naming China a currency manipulator is mostly “just a jaw-boning exercise,” said Amanda DeBusk, chair of the international trade department at the law firm of Hughes Hubbard & Reed and a former Commerce Department official. “There’s no immediate consequence.”

Is China guilty of using currency to help its exporters?

For years, China pretty clearly manipulated its currency to gain an advantage over global competitors. It bought foreign currencies, the U.S. dollar in particular, to push them higher against the yuan. As it did, it accumulated vast foreign currency reserves -- nearly $4 trillion worth by mid-2014.

But now the Chinese economy is slowing, and Chinese companies and individuals have begun to invest more heavily outside the country. As their money leaves China, it puts downward pressure on the yuan.

The yuan has dropped nearly 7 percent against the dollar so far this year. The Chinese government has responded by draining its foreign exchange reserves to buy yuan, hoping to slow the currency’s fall. China’s reserves have dropped by $279 billion this year to $3.05 trillion.

If Beijing stepped back and let market forces determine the yuan’s level, it likely would fall even faster, giving Chinese exporters even more of a competitive edge.

So Beijing is doing the opposite of what Mr. Trump says it’s doing. Cornell University economist Eswar Prasad earlier this month called the president-elect’s plans to name China a currency manipulator “unmoored from reality.”

“The whole discussion is ironic,” said David Dollar, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a former official at the World Bank and U.S. Treasury Department. “It’s out of date.”

Could Mr. Trump do anything on his own?

Gary Hufbauer, an expert on trade law at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, noted that as president, Mr. Trump could nonetheless escalate any dispute over the currency on his own. Over the years, Congress has ceded the president broad authority to impose trade sanctions. Mr. Trump has threatened to slap a 45 percent tax, or tariff, on Chinese imports to punish it for unfair trade practices, including alleged currency manipulation.

Brookings’ Dollar said China likely would bring a case to the World Trade Organization “against any protectionist measures that are a violation of U.S. commitments to the WTO,” which oversees the rules of global commerce and rules on trade disputes.

Some trade analysts wonder if Mr. Trump is using the tariff threat as a negotiating tool to win concessions from China.

Whatever the U.S. motive, China has a consistent record of retaliating against trade sanctions. When the Obama administration slapped tariffs on Chinese tire imports in 2009, for instance, China lashed back by imposing a tax on U.S. chicken parts.

China’s Global Times newspaper, published by the ruling Communist Party’s People’s Daily, has already speculated that “China will take a tit-for-tat approach” if Mr. Trump’s tariffs are enacted. The paper suggested that Beijing might limit sales of Apple (AAPL) iPhones and Boeing (BA) jetliners in China.

“The Chinese are predictable and reliable,” DeBusk said. “If they get punched, they punch back.”