Trump tweet hits oil market, saying U.S. won't accept "artificially" high prices

Oil prices dropped Friday from three-year highs after President Trump said in a tweet the U.S. would not accept the "artificially very high" prices imposed on the market by the oil-producing cartel OPEC.

His tweet came as OPEC representatives met in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, to discuss ways to hold down production and keep prices up. While Trump did not say what the U.S. might do to reduce oil prices, analysts said he has several options.

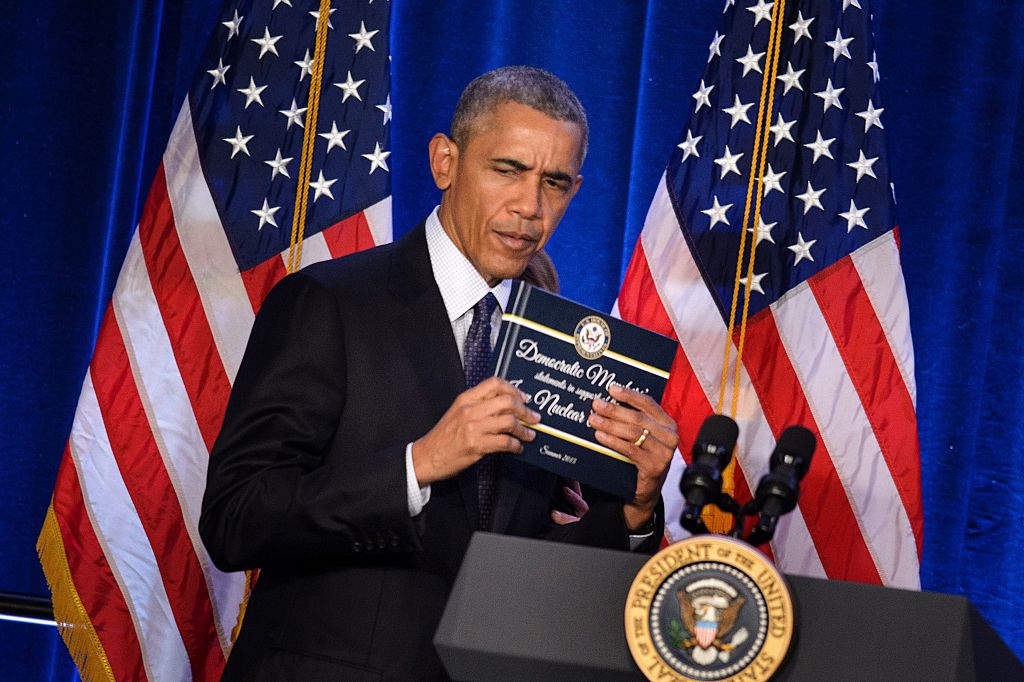

Chief among them would be to back off from his threat to withdraw the U.S. from the Iranian nuclear deal, said Ryan McKay, a commodities strategist with TD Securities. Exiting the agreement would open Iran up to further U.S. sanctions, possibly reducing the country's oil production.

"The easiest way to reduce oil prices would be to tone down the rhetoric about Iran," McKay said. "That alone has been a big reason why prices have risen."

Trump could also limit exports of oil produced in the U.S., said Patrick DeHaan, head of petroleum analysis at Gasbuddy.com, in an interview. In 2015, Congress legalized the export of U.S. crude, he said. As much as 10 percent of the total U.S. consumption of gasoline leaves the country in exports, he said.

A block in crude exports would be in line with other trade policies advocated by Trump, he said. The U.S. has during recent years increased its production capability so that it is now the world's third largest oil producer behind Russia and Saudi Arabia.

"The oil companies wouldn't like it," DeHaan said. "But limiting crude exports would allow more for use in the U.S., potentially lowering prices."

Oil prices have risen steadily since falling to just over $30 a barrel in early 2016. West Texas Intermediate, the U.S. benchmark, fell on Friday to $68.13 per barrel; Brent crude, used in international markets, also declined. Energy stocks slumped as well.

Another way the U.S. could try to push down oil prices would be for the Environmental Protection Agency to ease restrictions on the use of ethanol in gasoline products, DeHaan said. Again, this would not be contrary to other initiatives from the Trump administration. EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt has been active in rolling back environmental regulations across a broad range of areas.

Trump could also back off from his call to unwind vehicle fuel-efficiency standards, DeHaan said. "More efficient cars mean consumers use less gasoline, which over the long-term could reduce prices," he said.

Any call to provide subsidies to oil producers or open lands for production might also lower prices. "It's unlikely that Trump would actually do this," McKay said. "But if he did, the markets would react rather quickly."

Higher oil prices translate to increased costs at the pump for U.S. households and businesses and stoke fears of inflation. For every penny the price of gas increases, it costs consumers about $4 million a day. That equates to $1.4 billion a year, DeHaan said.

"A jump in oil prices preceded nearly every one of the prior downturns in the U.S. economy, and was the primary cause for a number of them," TD Securities analysts said in a research note.

The national gas price average rose to $2.71 a gallon earlier this week, its highest level since the summer of 2015, according to AAA. The price is 30 cents higher than it was this time last year, AAA said on its website. The U.S. Energy Information Administration forecasts that motorists this summer will pay an average of $2.74 for a gallon of regular gas, which would be the highest price for the busy driving season since 2014.

Higher gas prices have a chilling affect on consumer confidence, DeHaan said. "Consumers drive by maybe four or five gas stations a day," he said. "When they are barraged by higher gas prices it makes them less optimistic. Psychologically it's bad for the economy."