Trump finds new target in crusade against judges: Nationwide injunctions

Washington — President Trump has made no secret of his disapproval of a federal judge who temporarily blocked his administration's efforts to deport Venezuelan migrants suspected of being gang members under a 1789 law.

While the president's crusade has included calls for the judge, James Boasberg, to be impeached by the House, Mr. Trump and his administration are also taking aim at a form of judicial relief that has temporarily impeded implementation of his second-term agenda and also been a headache for his predecessors in the White House.

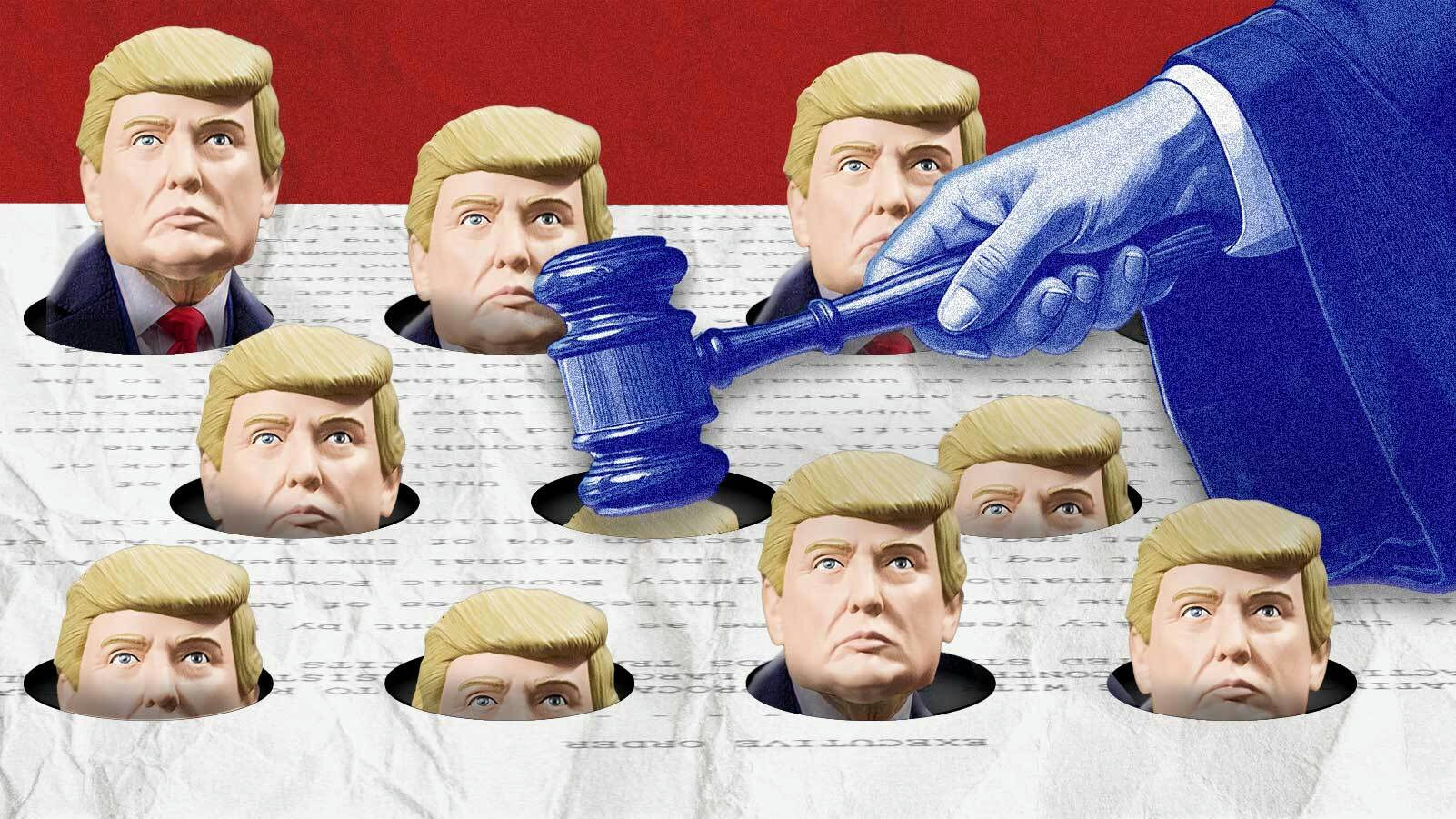

Known as nationwide or universal injunctions, at least a dozen of these orders have been issued by judges overseeing the more than 100 cases challenging the policies rolled out by Mr. Trump. District court judges have temporarily blocked the president's effort to ban transgender people from serving in the military, his executive order seeking to end birthright citizenship and the administration's mass firings of federal probationary workers, among others.

In other instances, including the president's attempt to invoke the wartime Alien Enemies Act to remove certain migrants, judges have issued temporary restraining orders that prevent enforcement of a policy, typically for 14 days, to allow for further proceedings.

Faced with these injunctions, many of which have been appealed, Mr. Trump and senior White House officials are now calling on Congress and the Supreme Court to take action to limit the ability of federal judges to issue orders that block policies nationwide.

"STOP NATIONWIDE INJUNCTIONS NOW, BEFORE IT IS TOO LATE," the president wrote Wednesday on Truth Social. "If Justice Roberts and the United States Supreme Court do not fix this toxic and unprecedented situation IMMEDIATELY, our Country is in very serious trouble!"

Stephen Miller, the White House deputy chief of staff, suggested that the administration's goal is to force action that ultimately curtails these orders.

"Our objective, one way or another, is to make clear that the district courts of this country do not have the authority to direct the functions of the executive branch. Period," he told Fox News in an interview Thursday.

When pressed on whether the administration is seeking broad change that restricts a district court's ability to block any executive branch policy, Miller said that "complete and permanent relief is what this administration seeks."

How injunctions work

Typically in the judicial system, courts focus on resolving the legitimate claims brought by the parties before them. While different courts may reach different outcomes, the broader legal questions can percolate before the Supreme Court may ultimately step in with a resolution.

But in the current landscape, there are many legal battles brought by many different litigants. In some instances, judges are issuing far-reaching orders that extend beyond the parties and bar the government from enforcing the policy at issue against anyone, anywhere in the country.

"Whatever your politics, we can agree that having all of these really important policy questions and legal questions resolved in whatever court somebody can first convince to offer nationwide relief is not the best way to run the system," said Jonathan Adler, a law professor at Case Western Reserve University. "But fixing it in a balanced and nuanced way probably requires legislation."

The Trump administration is not the first to complain about nationwide injunctions, and Mr. Trump is not the first president to have his policies derailed by them.

A study published in the Harvard Law Review last April found that at least 127 nationwide injunctions were issued from 1963 through 2023. Building on a dataset from the Justice Department, researchers identified 96 that had been entered by judges since 2001. Sixty-four of those temporarily blocked policies issued in Mr. Trump's first term, while federal judges issued 14 nationwide injunctions in challenges to President Joe Biden's proposals through the end of his third year in office. Miller himself repeatedly touted injunctions against Biden administration policies that the legal group he led obtained.

When looking at the judges who entered these orders, the study found that of the 64 nationwide injunctions imposed during Mr. Trump's first term, 92% came from judges appointed by Democratic presidents. For Biden, all of the 14 injunctions were issued by Republican-appointed judges.

"It's a broader trend. It has affected administrations of more than one party, and it will affect the next Democratic administration as well," Adler said.

Mr. Trump's condemnation of nationwide injunctions has sparked interest from Congress. Sen. Josh Hawley, a Republican from Missouri, said he plans to introduce legislation to restrict district judges' ability to issue them.

A bill from Rep. Darrell Issa, a California Republican, would also restrict federal judges' authority to impose nationwide injunctions. An amendment to his proposal that was approved by the House Judiciary Committee earlier this month would allow the broad orders in some instances, such as in cases brought by multiple states if they're heard by a three-judge district court panel.

Bills reforming nationwide injunctions have also been introduced by Democrats. In 2023, Democratic Sen. Mazie Hirono of Hawaii proposed requiring cases that seek nationwide injunctive relief to be heard by the federal district court in Washington, D.C. Another plan, from Democratic Rep. Mikie Sherrill of New Jersey, would require civil suits seeking nationwide orders to be filed in district courts with at least two active judges, an effort to prevent so-called forum shopping, where plaintiffs go looking for a friendly judge who is guaranteed to take a case in a certain district.

The House and Senate Judiciary Committees also held hearings on the topic in 2017 and 2020, respectively.

Injunctions at the Supreme Court

At the Supreme Court, several justices have taken note of the uptick in nationwide injunctions.

In its last term, during arguments over the availability of the abortion pill mifepristone brought by a group of anti-abortion rights doctors, Justice Neil Gorsuch lamented what he said is a "rash" of these broad orders.

"This case seems like a prime example of turning what could be a small lawsuit into a nationwide legislative assembly on an FDA rule or any other federal government action," he said during arguments last March.

In that dispute, U.S. District Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, appointed by Mr. Trump in his first term, issued a sweeping order that suspended the Food and Drug Administration's 2000 approval of mifepristone. The high court last year rejected a challenge from the anti-abortion rights doctors to reinstate more stringent rules for obtaining the drug, preserving access to it.

In 2022, Justice Elena Kagan spoke out against the ability of a single judge to stop implementation of a policy across the country.

"In the Trump years, people used to go to the Northern District of California, and in the Biden years, they go to Texas," she said, referring to where challengers filed their lawsuits. "It just can't be right that one district judge can stop a nationwide policy in its tracks and leave it stopped for the years that it takes to go through the normal process."

Justice Clarence Thomas also questioned district courts' authority to enter universal injunctions in 2018, when the Supreme Court upheld the travel ban Mr. Trump implemented in his first term.

"If their popularity continues, this court must address their legality," Thomas wrote in a concurring opinion.

The high court was recently given the opportunity to address the lawfulness of nationwide injunctions, when the Biden administration filed a request for emergency relief in December and suggested it settle the question of district court's entering preliminary relief on a universal basis.

"Universal injunctions exert substantial pressure on this court's emergency docket, and they visit substantial disruption on the execution of the laws," then-Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar wrote in a filing. Quoting Gorsuch, she wrote that the "'patently unworkable' practice of issuing universal injunctions has accordingly persisted."

But the high court declined to do so.

Now, the Trump administration is taking its turn in urging the high court to resolve the fight. In requests for emergency relief stemming from three district court injunctions blocking the president's executive order seeking to end birthright citizenship, acting Solicitor General Sarah Harris said the orders harm the courts and the government.

"Government-by-universal-injunction has persisted long enough, and has reached a fever pitch in recent weeks," she wrote. "It is long past time to restore district courts to their 'proper — and properly limited — role … in a democratic society.'"

The Supreme Court is unlikely to decide whether to grant the administration's request to narrow the scope of the injunctions until early April.