Tropical deforestation on the rise, contrary to reports

Tropical forests from Indonesia to the Amazon are being lost an astonishing rate, with a new study suggesting deforestation has intensified 62 percent in just 20 years.

The study also calls into question a more optimistic picture from U.N.'s Food and Agriculture Organization's assessment, which found the rate of deforestation had actually decreased 25 percent during the period stretching from 1990 until 2010.

"It is not good news," said Do-Hyung Kim, lead author of the new study to be published in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union. "Between 1990 and 2010, it shows all these efforts to cut the deforestation rates were not effective."

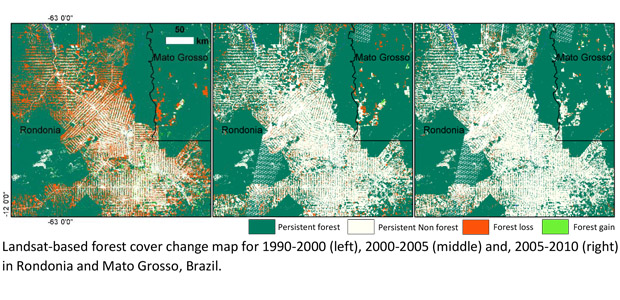

While the FAO assessment was based on country reports, Kim and his University of Maryland colleagues Joseph Sexton and John Townshend used satellite data. By analyzing 5,444 Landsat images from 1990, 2000, 2005 and 2010, they were able to gauge how much forest was lost or gained in 34 forested countries which comprise 80 percent of forested tropical lands.

They found that during the 1990-2000 period the annual net forest loss across all the countries was 4 million hectares (15,000 square miles) per year. From 2000 to 2010, the net forest loss rose 62 percent to 6.5 million hectares (25,000 square miles) per year, equivalent to clear-cutting an area the size of West Virginia.

In that same time, the U.N. reported a 25 percent decrease.

The University of Maryland study found that tropical Latin America showed the largest increase of annual net loss - 1.4 million hectares (5,400 square miles) per year from the 1990s to the 2000s. Of those countries, Brazil topped the list with an annual 0.6 million-hectare loss (2,300 square miles) per year.

Tropical Asia showed the second largest increase, at 0.8 million hectares (3,100 square miles) per year, led by Indonesia, Malaysia, Cambodia, Thailand and the Philippines. Tropical Africa showed the least amount of annual net forest area loss among the three major regions studied.

Much of this deforestation has been driven by illegal logging and, more recently, the conversion of land to palm oil, soybean and other plantations.

Given that deforestation contributes to as much 20 percent to global warming, the international community has dumped billions of dollars into solving the problem. Among those efforts are the U.N. program known as REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) which gets cash for conservation into the hands of poor countries to help reduce deforestation.

But even with all that money, it can be hard to solve a problem that thrives on corruption and lax law enforcement in some of the world's poorest countries and has becoming increasingly mechanized, with bandits trading axes for chain saws and then earth moving equipment.

Some scientists are turning to new technologies such as satellite imaging to try to hold nations accountable for their deforestation and reforestation promises.

While Kim said international efforts overall have born little fruit, he acknowledged there were some signs of progress toward the end of the study period with Brazil deforestation rates dropping - though more recent data in 2013 showed they had spiked again.

"Brazil is showing some hope," Kim said, referring to the 2006 decision by major soybean traders not to purchase soy produced in the Amazon's deforested land.

Douglas Morton, who studies forest cover by satellite sensing at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and was not a coauthor on the paper, said the new, satellite-based study "really provides a benchmark of tropical forest clearing not provided by other means."

Fred Stolle, an expert on satellite monitoring of forests at the World Resources Institute, also praised the study, saying it provided more evidence "that tropical deforestation remains an urgent challenge."

"In order to combat these trends, more needs to be done to minimize the impact the production of commodities--especially palm oil, timber, beef, and soy--on forests," Stolle said. "Fortunately, the technology used to monitor forests is continuously improving, providing more accurate and timely data to inform forest management, conservation and restoration efforts."

Kim said he was hopeful that his study would prompt the FAO to consider using more remote-sensing data in their assessments, thus ensuring its findings, which shape global forestry policies, would be more consistent and reliable.

FAO Senior Forestry Officer Kenneth MacDicken defended their assessment, saying there were multiple reasons why Kim's study may have come up with different findings. Among them is that that forests are constantly changing - plantations, for example, are planted and then harvested - and that "remote sensing doesn't capture" dry forests in the tropics which are spaced further apart in Brazil and Africa and don't have leaves for much of the year.

"Measuring forests using satellite imagery and measuring and reporting them from ground-based measurements both have value, but comparing them directly should be done with great caution," MacDicken told CBS News. "It's like comparing apples and oranges."

The FAO is set to issue a fresh forestry assessment in September at the World Forestry Congress.