Travels with the "Green Book"

Watching Mary Wilson, feeling the love at New York's glamorous Café Carlyle, it's hard to imagine what she felt at the age of 19 when, as a newly-minted Supreme just out of high school, she went on her first-ever road tour with a regular who's-who of Motown stars. Traveling by bus with Stevie Wonder, Mary Wells, The Temptations and others, Wilson was confronted by hate in the still-segregated South.

She recalled. "We were getting off the bus, and there were gunshots."

"They were shooting at the bus?" asked correspondent Martha Teichner.

"Oh, yeah. We had several holes in the bus," said Wilson. "You know, your parents had told you, 'Be careful, da da dah dah dah.' You knew about the segregation, but I mean, the gunshot sort of brought it right into your face and saying, you could be killed."

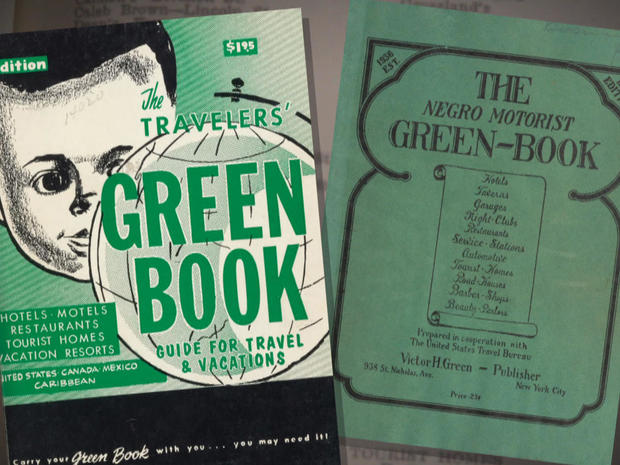

It was this chilling fact of life, the racism that in 1936 inspired "The Negro Motorist Green Book." Victor Green, a postal worker who lived in Harlem, began publishing a guide to businesses that welcomed African American travelers.

In each year's edition, a warning: "Carry your Green Book with you. You may need it."

At the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., visitors can experience the not-so-long-gone era of the "Green Book."

"I remember as a little child going down South from Detroit and my parents had to be strategic as to where we stopped," said one visitor at the exhibit.

"It was after the Depression, before the war, when the auto culture was really burgeoning, and there were more jobs for black people," said cultural historian Candacy Taylor, whose book about "The Green Book" will be published this fall. "By the '40s, the second wave of the Great Migration was underway, and so you had 1.5 million black people leaving the South during that time."

At risk if they owned nice cars. Taylor told the story of her stepfather's family being stopped and relying on a tried-and-true subterfuge for avoiding trouble: "His dad worked for the railroad, had a good job. And his mother was sitting in the front seat. So, the sheriff comes to the door and says, you know, 'Who's this car? Where are you going? Who are these people with you?' And his father says, you know, 'This is my employer's car.' And he looked to his wife. And he said, 'And she's the maid. And this is her son.'

"And then the next question was, 'Well. where's your hat?' Meaning the chauffeur's hat. And he said, 'It's hanging right in the back, officer.'"

Essentials for driving in and out of the Jim Crow South: A chauffeur's hat, and the Green Book. "The 'Green Book' was like a Bible. You did not leave home without it," said Alice Clay Broadwater, who was a teacher traveling with her lawyer-husband and small children between Boston and the South. She relied on the book.

"Black travelers in those days, in the '50s, had to carry the Green Book if they needed to stay overnight someplace, or if they wanted to know where they could eat," Broadwater said.

Unless, of course, there were no Green Book listings en route. "It was not only frightening, it was very unsafe," she said. "If you're stopping on the side of the road, you can't really sleep."

"So, you'd pull off the road to take a nap or to sleep because there was no place else?" asked Teichner.

"Absolutely."

"Route 66" was a huge hit for Nat King Cole, but here's the irony: for black travelers looking for places to stay along its more than 2,400 miles, good luck. "Green Book" sites were scarce. So-called "sundown towns" were plentiful.

"You'd see a sign on the way in, 'N-word, don't let the sun set on you here,'" recalled Taylor. "You could have a 'Green Book,' but you could still find yourself in a sundown town at the wrong time. And sometimes you'd be escorted out of town by law enforcement. Sometimes you'd be harassed, or chased, or worse."

Often a safe place to stay was a room in someone's house. Since 2014, a historical marker has stood outside a Green Book-listed tourist home in Columbia, S.C., run by Reggie Scott's mother and aunt.

Eighty-nine now, Scott grew up in the Harriet M. Cornwell Tourist Home, and became a musician because of the players who stayed here. "Cab Calloway was my greatest excitement," Scott said. "He came to the house."

If there's one common denominator Teichner found doing this story, it is the musicians, the unbelievably famous names who were also victims of segregation.

The Rossonian Hotel and Lounge in Denver was one of more than 80 businesses in the area listed in "The Green Book." "Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday stayed here," Taylor said. "A lot of times they were performing downtown, where they were welcomed to perform, but not welcomed to stay."

As Taylor took pictures throughout the Rossonian, now undergoing renovation, she said, "These places carry a spirit with them, you know, which is why it's so important that they're still here."

Taylor put 23,000 miles on her car during just one of her trips around the country documenting more than 9,600 of the "Green Book" sites. "If I had to guess, I'd say about at least 85% were black-owned. But there were sites like Charlie's Sandwich Shoppe in Boston. That was in Southie; that was owned by a white man."

Charlie Poulous, a Greek immigrant, opened the restaurant in 1927, and with his partner, Christi Manjourides, served all races, possibly the first restaurant in Boston to do so.

Damian Marciante, who bought Charlie's in 2017, said there was some backlash: "The original owners did not care. They just welcomed everybody. If you didn't like it, you didn't come in."

It didn't hurt that the Black Pullman Porters Union had its headquarters upstairs. The railroad workers spread the word about Charlie's even before it began listing in the "Green Book" in 1947.

And of course, the jazz greats read their "Green Books," and came to Charlie's, including Sammy Davis Jr. "He used to tap dance out in front of the diner," Marciante said.

As times changed, so did "The Green Book." For sale by subscription and at Esso gas stations, in its heyday it sold two million copies a year. But in the 1948 edition, Victor Green wrote: "There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. This is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States."

Green, who died in 1960, didn't live to see that day come, when the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964 mandating the end of segregation. Publication of "The Green Book" ceased in 1967. It was largely forgotten, its true legacy underestimated.

Taylor said, "It's so important that we look at the 'Green Book' not just as a historic travel guide, not as just something that we needed in the past, but what the 'Green Book' teaches us about the resilience and the courage of what black people were able to do and accomplish, in spite of the circumstances, and everything that happened."

For more info:

- Candacy Taylor (taylormadeculture.com)

- The Green Book Project

- "The Green Book" (New York Public Library)

- "Unpacking the Green Book" (Museum of Arts and Design exhibition, now closed)

- National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, D.C.

- Rossonian Hotel, Denver (Palisade Partners)

- Harriet M. Cornwell Tourist Home, Columbia, S.C. (South Caroline Department of Archives and History)

- Charlie's Sandwich Shoppe, Boston

- Café Carlyle, New York City

Story produced by Robbyn McFadden.