Inside the genetic genealogy being used to solve crimes

On April 25th of this year, authorities in Sacramento, California announced, to great fanfare, that they had solved a notorious 40-year-old cold case and arrested a man they say is the Golden State Killer, a clever, sadistic serial murderer and rapist who terrified the state back in the 1970s and 80s. But more significant than the arrest, was the way it came about; using a powerful new tool called 'genetic genealogy,' which law enforcement says has since been used to crack cold cases all over the country. It is a mixture of high-tech DNA analysis, high speed computer technology, and old fashioned family genealogy pioneered by some quirky collaborators who got into it as a hobby. In just six months, it has opened up a new frontier in criminology and also raised questions about privacy and the ethics of using DNA.

The search for the Golden State Killer had frustrated law enforcement for decades. 13 grisly murders and as many as 50 rapes. Sometimes followed up with terrifying phone calls to surviving victims.

The police never had a good lead until this year. It wasn't a new witness or a snitch, but something that they had had for years: the killer's DNA. They knew everything about his genetic make up. But not his identity. No matches in law enforcement computers.

Then just before his retirement, cold case investigator Paul Holes pursued a final gambit. Using an alias, he submitted the killer's DNA to an obscure public data base called GEDmatch, popular with genealogy enthusiasts and good at finding family members.

Paul Holes: If we can't find him, can we find somebody related to him? And then work our way back to him? And so ultimately, that's what we did.

And it worked. After months of research and investigation, the twisted strands of family DNA led them to the doorstep of one of their own, a retired police officer.

Press Conference: My detectives arrested James Joseph DeAngelo, 72 years old living in Citrus Heights

Authorities had surreptitiously obtained a fresh DNA sample from DeAngelo and, according to the arrest warrant, it was an identical match to that of the Golden State Killer.

Since that very first case in April, local law enforcement agencies around the country have used the technique to make arrests in at least 11 other cold cases.

All of them would still be cold, if it weren't for Curtis Rogers, a retired octogenarian in Lake Worth, Florida who runs the largest, public DNA database in the U.S. out of this three-room bungalow.

Curtis Rogers: This is our headquarters for GEDmatch.

Steve Kroft: This is it?

Curtis Rogers: This is it. It was built in 1925.

Steve Kroft: How many employees do you have?

Curtis Rogers: None.

Rogers, a retired Quaker Oats executive and genealogy buff, started GEDmatch eight years ago as a hobby along with his partner John Olson, an accomplished computer engineer in Texas.

Curtis Rogers: These are all first cousins.

They wanted to provide a free, open-source website where people could upload their DNA file and search for relatives and ancestors.

Steve Kroft: Did you know the police were using this to solve crimes?

Curtis Rogers: Not at all. There was an email from one of our users that said GEDmatch was involved in finding the Golden State Killer. That was the first I knew of it. My world turned upside down at that point.

Steve Kroft: In what way?

Curtis Rogers: By the time I got to work. There were satellite trucks up and down this little narrow street that we're on. There were reporters knocking on the door. I-- it w- as-- you know, what do I do?

Steve Kroft: You were upset?

Curtis Rogers: Oh, yes. Oh, yes.

Steve Kroft: About what?

Curtis Rogers: About whether we were invading our user-- users' privacy in some way that they had no expectation of it being invaded.

GEDmatch's policy statement, which had already cautioned that the public site might be used for purposes other than genealogy, notified its community that people could withdraw their file if they didn't want their DNA used by police to solve crimes.

Curtis Rogers: So the blue indicates that there's a match there.

While its office in Florida is spartan, its computer servers in an Oregon data center are not.

They can compare 600,000 separate locations in one person's DNA to those of its 1 million users and determine family matches in just four to five hours, listing as many as 2,000 distant relatives with the closest ones at the top of the page along with their contact information.

Steve Kroft: And then you have the email address of the people that it belongs to.

Curtis Rogers: Correct.

Steve Kroft: So if you wanna call 'em or if you wanna e-mail 'em, you can just--

Curtis Rogers: You can email them. Genealogy is-- is a contact sport. You want to contact people.

Rogers says GEDmatch is not in the business of finding criminals or solving crimes. He says it can be used by law enforcement to develop initial leads, but it's just the first step in a long process that requires special skills to turn hundreds of possibilities into a handful of suspects.

Curtis Rogers: Law enforcement can't do this, it takes an expert genealogist, that's CeCe, she is the best of the best.

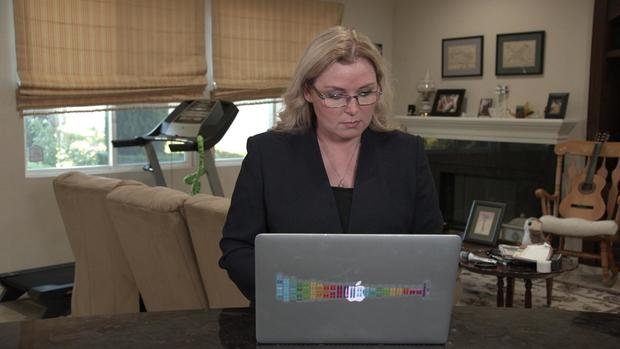

He's talking about CeCe Moore – genealogy is a small world – she has spent most of the past decade working alone out of her home near San Diego helping people identify their birth parents, and putting names on the unknown dead. A precursor to her latest calling.

CeCe Moore: When I would be asked, "What do I do?" I'd say, "Well, I'm a professional genetic genealogist." And people would just look at me blankly, like, "What is that?"

People are just beginning to find out. CeCe Moore is now the lead genealogist for Parabon NanoLabs, a small DNA technology company in Reston, Virginia that is leading the way in genetic genealogy.

Press conference in Champaign, Illinois: "The Sheriff's office arrested Michael F.A. Henslick. Without Incident."

The day we visited her, police halfway across the country announced that they had made an arrest on a nine-year-old murder case that she'd been working on.

CeCe Moore: This was just this morning, a couple hours ago.

Steve Kroft: Where abouts?

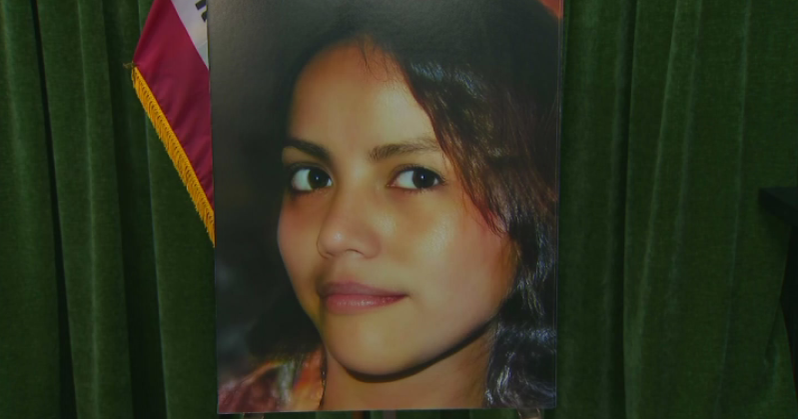

CeCe Moore: In Champaign, Illinois. This is the Holly Cassano murder. She had been stabbed repeatedly, I think about 60 times in her mobile home. And she was a young, single mother.

Moore has played a pivotal role in identifying suspects in 13 of the 14 cases since the Golden State Killer opened the floodgates six months ago.

CeCe Moore: I'm looking at the people who share the most DNA with the unknown suspect.

She does it by taking the partial family matches that are generated by GEDmatch and builds out family trees that she hopes will point to the unknown suspect.

CeCe Moore: So our unknown subject is here. Okay, so he's sharing DNA with this person and this person.

Steve Kroft: But two different family trees?

CeCe Moore: Yeah.

This is how she how identified the alleged killer in a high profile, 31-year-old double homicide.

CeCe Moore: And I'm trying to find an intersection where these two family trees come together so we're getting that right mix of DNA. So I'm building these down. I'm saying: who are their children, who are their children, theirs, theirs, and theirs?

She uses things like marriage licenses, birth announcements obituaries even Facebook to trace the ancestors.

CeCe Moore: I found an obituary. And that obituary had a descendant from this tree carrying a surname that I recognized from this tree and I was able to find their marriage record. So a descendant from this couple and a descendant from this couple married and had only one son.

Steve Kroft: That's fascinating.

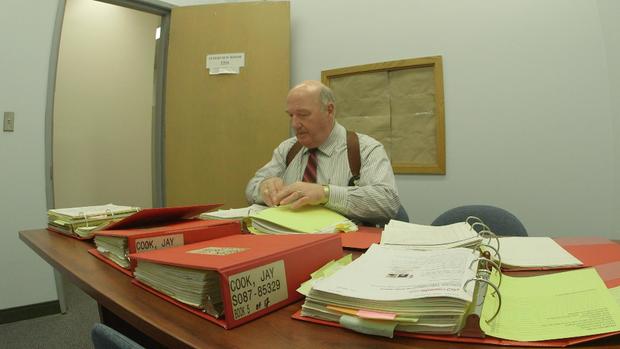

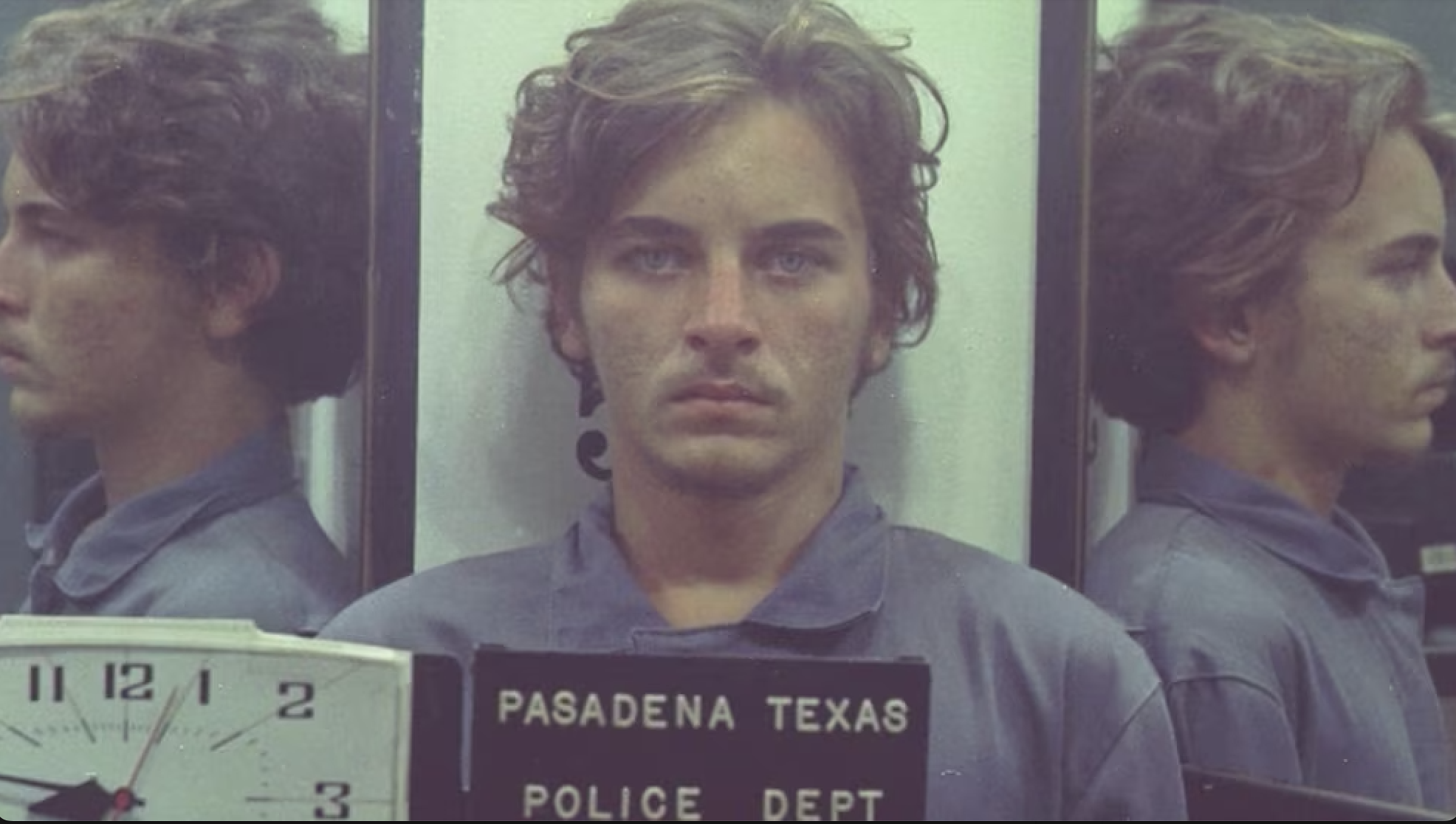

That one son was William Earl Talbott II, the only male carrier of the DNA mix from the two families that could match the DNA found at the gruesome homicide scenes of Jay Cook and Tanya Van Cuylenborg, the young Canadian couple was brutally murdered in 1987 in Washington State. CeCe's report went to Detective Jim Scharf, who had worked the cold case for 13 years.

Detective Jim Scharf: This was the tip of a lifetime to solve this case.

He said Talbot was never even on their radar but at the time of the murders he was 24-years-old and living not far from where the bodies were discovered. Police tailed Talbott, collected his DNA from a discarded cup, and turned it over to a crime lab technician for analysis.

Detective Jim Scharf: And she told me that we had a match to the suspect that killed Tanya and Jay. And it brought tears to my eyes. And then I screamed. "Yeah!" (LAUGH) You know, "we got him!"

CeCe Moore: When I give these names to law enforcement, I am really sure. Because all those pieces have to come together in a really specific way. And then for them to end up right in the town where these crimes happened, it can't be a coincidence.

Steve Kroft: Do you remember the day-- when you-- figured out who it was?

CeCe Moore: Yes. I remember-- I remember the moment when I finally get to all of these people. It's 'cause it's a pretty profound moment-- to zero in on that. It's certainly a heavy discovery.

Steve Kroft: Why?

CeCe Moore: Well, if I'm right, which I believe I am, I know a secret that only the killer knows or only the rapist knows. It's-- you know, it's-- it's a profound thing. This has changed lives. And-- you know, I see what I believe is the answer.

One of the hardest answers to come up with was who killed 8-year-old April Tinsley, who was abducted while playing outside her home in 1988. Her body was discovered three days later in a ditch outside Ft. Wayne, Indiana. She had been raped and murdered. The police had the DNA of her killer, but could never find a match. For 30 years he taunted investigators, scrawling threats on a barn door and tying notes to girls' bicycle seats.

Detective Brian Martin: The amount of interviews, man hours that went into this case is unbelievable.

Brian Martin has been a Ft. Wayne homicide detective for six years. He was the one who got the call in July from CeCe Moore saying there had been a breakthrough.

Detective Brian Martin: We began looking at the individuals that she had given us, and within four to five hours, we began surveillance. 14 days later, that individual was taken into custody and is currently in the Allen County Jail.

The suspect is John Miller, a 59-year-old loner, who worked at Walmart and lived in this trailer six miles away from where April's body was found. He's pled not guilty, but according to this affidavit, when police went to arrest him, they asked Miller if he had any idea why they wanted to talk to him. Miller looked at them and said, "April Tinsley."

CeCe Moore: He knew exactly what it was for.

Steve Kroft: Is that the most satisfying part of the job?

CeCe Moore: There's two things that are satisfying. Finally having the pieces come together is very satisfying. And then giving these families some justice to have an arrest. That is the most meaningful thing to me.

The support for genetic genealogy in the law enforcement community is virtually unanimous. Parabon NanoLabs , the company CeCe Moore works for, had been anticipating it for years. It's already marketing technology to police agencies that create computer generated composites of suspects, predicting eye color, skin tone, and perhaps even facial structure based on their DNA. Steve Armentrout is Parabon's CEO.

Steve Kroft: So you were ready when the Golden State case happened.

Steve Armentrout: Yeah. The wheels were already in motion. We sat back and watched the public response. It was overwhelmingly positive. This was like a starting gun to go ahead and move out.

Armentrout says Parabon already has more than a hundred cases in the pipeline. But there is no shortage of cautionary questions being raised by civil rights groups and bioethicists about the reliability of crime scene DNA, the lack of standards and protocol in a revolutionary new field. And whether website users have become genetic informants on their relatives. The field is so new it's almost impossible to predict consequences. None of the cases have gone to trial and no one has pled guilty.

Steve Kroft: Do you anticipate that there will be legal objections?

CeCe Moore: Sure. I would think any good defense attorney is going to challenge this, just because there has never been a precedent-setting decision on specifically using genetic genealogy and GEDmatch. So I look forward to the day that we get that decision.

Produced by Michael Karzis. Associate producer, Katie Brennan.