Top global security threats with expert Frederick Kagan — "Intelligence Matters"

In this episode of "Intelligence Matters," host Michael Morell talks with Frederick Kagan, director of the Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute, about the current landscape of global security threats from the likes of Russia, China, Iran and North Korea. Kagan and Morell discuss Russian president Vladimir Putin's options and objectives in the war in Ukraine and the lessons China's Xi Jinping may be drawing from the conflict. Kagan also offers insights into the effect of recent protests on the Iranian regime's stability and the nuclear ambitions of both Tehran and Pyongyang.

HIGHLIGHTS:

- On Putin taking the "long view" in Ukraine: "Putin has been in office for 20 years now, 22 years. He's been waging this war, as you noted, since 2014. Actually, he's been setting conditions for even longer than that. He's taking a long view here. And the territory in Ukraine that he's occupied would leave Ukraine strategically vulnerable to a future Russian attack and economically crippled. That would leave Russia in a much more advantageous position for a renewed attack in the future than it had at the start of this."

- Ukraine war stakes: "[W]e all have been far too quick to decide that Putin has already lost. He hasn't. If he ends this phase of this war with the battle lines anywhere close to where they are right now, it will have been a significant, if extraordinarily costly, victory for Russia and it will be portrayed as such. If we want Putin to lose, and I think it's very important that he does lose, then the Ukrainians are going to have to liberate a lot more of their territory and we'd have to help them. So I actually think the jury's still out on that. And that's one of the reasons why Putin keeps fighting. And it's one of the reasons why he's not interested in negotiating on any serious terms right now, because he still thinks he can win."

- Constraining Iran's nuclear program: "I don't think that there is a way to prevent Iran from becoming a nuclear weapon state that doesn't involve a very significant military operation. And even that, I think, would be dicey in its own right in many ways. And I'm not advocating it. But even that is questionable in its ability to stop them. So I think we're in a very, very bad situation. [...] Bottom line is, we're in a very, very bad place when fundamentally the decision rests with Khamenei about what kind of nuclear power Iran wants Iran to be rather than about whether Iran can be a nuclear power. And unfortunately, I do think that that's where we are right now."

Download, rate and subscribe here: iTunes, Spotify and Stitcher.

INTELLIGENCE MATTERS – FREDERICK KAGAN

MICHAEL MORELL: Fred, welcome. It is great to have you on Intelligence Matters.

FRED KAGAN: Mike, it's great to be with you. Thanks so much for having me.

MICHAEL MORELL: So, Fred, I just want to start by asking you about the Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute, which you direct. What is the project? What are you guys doing with it?

FRED KAGAN: So we are an open-source intelligence organization at the American Enterprise Institute. I founded CTP in about 2009 and we use publicly available information and do our best to apply intelligence community-type tradecraft and standards to it in order to inform the public, the media amd policy community, and make recommendations about policy for American national interests.

We have two analytical teams at CTP. One focuses on Iran and increasingly Iran and its activities in the region. But the team has been very focused historically on Iranian internal matters, has been covering the data, the Iranian protest movement, with daily updates. And the other team is a Salafi jihadi team that looks at the Salafi jihadi movement, particularly as it has been operating in Africa and secondarily in Yemen, although we're finally managing to get our coverage back into the Middle East, particularly Iraq and Syria.

MICHAEL MORELL: So, Fred, you obviously don't know the information base that the intelligence community operates from on these issues. But how strong is the open source information that's out there, the publicly available information? How has that changed over time? Do you have what you need to make judgments? What's the quality of that information? Can you talk about that a little bit?

FRED KAGAN: Sure. So weirdly, I actually do have some understanding of what the base has been that the IC uses, because I spent about 18 months in Afghanistan with General Petraeus and then General Allen. And I spent most of that time in the joint intelligence operations center there. So I got a pretty good view of what the IC work was on the kind of conflict that we follow. And I think that has helped me refine my understanding of what I think you can do from publicly available information and what you can do with that, what you can only do with the exquisite intelligence.

In general terms, if you want to build a baseline understanding of what's going on in the world in a conflict zone, I think publicly available information is the way to go. My general impression of the intelligence community, maybe this has changed, is that the exquisite intelligence tends to come through a lot of soda straws that are relatively confined, and it is a challenge to take that highly sort of targeted soda straw information and build a general picture of what's going on from it.

Whereas on the publicly available information side, it's there. There are lots of things that you just can't know that you really do need to know in order to make the kinds of decisions that our leaders actually have to be making. So my view is that you, the intelligence community, and we all would do well to build our baseline understanding of what's going on in the world from publicly available information and then use the exquisite intelligence to answer the questions that you can only answer in that way and perform the functions that can only be performed in that way. And that's specifically things like targeting right now, developing really actionable intelligence in a timely fashion and so on.

MICHAEL MORELL: Fred, I want to talk about the many national security issues that are facing the United States today. But before we do that, I'm sure you know that we're fast approaching the 20th anniversary of the war in Iraq. And I wanted to ask you a couple of questions about the war.

You wrote a report on Iraq in January 2007, I think - I think that was the date – that outlined a set of recommendations for the president. And my understanding that he was impressed with your report and actually helped guide his decision-making into a set of decisions that ultimately were successful in stabilizing the country. And what I want to ask is, why do you think the the strategy in Iraq, the surge strategy in Iraq, was successful and why a similar strategy in Afghanistan was not?

FRED KAGAN: It's a great question. Obviously, a very complicated one. Obviously, Afghanistan is not Iraq. Situations are were different and the problems were somewhat different. The commonality was that in both cases, the U.S. and its allies were facing an insurgency, and we hadn't recognized that we were facing an insurgency. And so we hadn't adopted a counterinsurgency strategy, and then we hadn't resourced it.

So this surge is both in Iraq and Afghanistan. We're always, as you as you know, less about force numbers and more about recognizing that it was an insurgency and adopting a counterinsurgency approach. I could make the very straightforward observation that whereas in Iraq, the surge was allowed almost all of the time and space that it was projected to require in order to achieve its effects before President Obama ordered the significant drawdowns, in Afghanistan, President Obama announced a timeline for the surge to end that was earlier than certainly I thought was appropriate or would be adequate.

And in fact, while I was in theater, I observed the effects of that order, that there were areas of Afghanistan that needed to be cleared by surge forces that the ISAF couldn't clear because the surge had to be withdrawn for President Obama's orders before we could do that.

So it was an incompleted effort, as a result of the President's decisions on timelines. But that's not a sufficient answer. I think that we had a much more effective civil military or political military campaign plan and working relationship throughout the surge period in Iraq, principally between General Petraeus and Ambassador Ryan Crocker. And we didn't have that in Afghanistan for many reasons.

So we never, I don't think we ever really got a political approach in Afghanistan that aligned fully with the military approach for various reasons. And the political situation was very dicey.

For all of that, I have to say that I think that by the time President Biden came to office, the situation in Afghanistan was relatively stable with a very low level of U.S. forces present, taking very, very few casualties. And I think that if President Biden had not ordered the hasty withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan, Taliban would not now be in power there and the country would not have collapsed.

So I don't think that – clearly the surge in Afghanistan did not succeed as well as the surge in Iraq for various reasons. But I also think that there was nothing inevitable about the outcome that we've had.

MICHAEL MORELL: Okay, Fred, let's move to today. And what I want to do is, is move through the hot spots in the world. And no surprise. I want to start with the war in Ukraine. As you know, we're coming up on the one year anniversary of the invasion, fully realizing that this war really began in 2014, but the massive invasion from last February. And I want to begin with the most basic question, which I don't think gets discussed enough in the United States: Why does the outcome of this war matter to us?

FRED KAGAN: The outcome of the war matters to the U.S. and Europe profoundly. Putin is trying to establish the principle that – basically Putin is trying to bring back into existence a Hobbesian world. You know, it's a war of all against all. It's a world in which the strong do what they wish and the weak submit to what they must. Sovereignty is defined by military power. And it's not a world that we have lived in for many, many decades. And it's not a world that we want to live in. And if Putin is allowed to establish this principle, then Xi Jinping is observing this and will be encouraged. The Iranians will be encouraged to do this. Any country that is more powerful than a neighbor with whom it has a grievance will be encouraged to to decide to resolve its conflicts by force. That's a terrible world for us to live in, especially considering the proliferation of nuclear weapons.

Which brings me to my next point. You could make the case that the only reason this war is occurring is because Ukraine gave up the Soviet nuclear arsenal or the part of the Soviet nuclear arsenal that it had inherited. It gave that up in 1994 at our insistence, and in exchange for a commitment by us and the Russians to respect its boundaries. The fact that it gave up that arsenal and then the Russians have invaded says a lot of bad things to other countries that are pursuing or thinking about pursuing nuclear weapons. So from both of those perspectives, it's deeply concerning. There are others, but I'll stop there for now.

MICHAEL MORELL: So from a from a strategic perspective, Fred, where are we in the war today? What are the possible paths going forward and what will determine which of those paths we end up on?

FRED KAGAN: So the Russians began this war with an illegal, unprovoked, unjustified, massive invasion that failed disastrously. And the Ukrainians obviously pushed them back and then were able to liberate or to liberate large portions of their territory.

The Ukrainians don't have a defense industry of their own that is significant and have needed Western help. The West has stepped up for the most part, but Western hesitation to provide Ukraine with the weapons and equipment that it needs in a timely fashion and at scale has now, I fear, cost the Ukrainians the opportunity to continue the counteroffensive that they had begun in the fall, as a result of which we're now looking at the Russian offensive operations in the east already underway and possibly gearing up for yet another major offensive operation, even as the Ukrainians seem to be trying to get ready for their own counteroffensive. This is unfortunate.

I think that if we had provided Ukraine with the weapons that it needed in more timely fashion, the Ukrainians probably could have continued their counter offensive operations in the fall and over the winter and retained the initiative. Now, the initiative is a bit of a jump ball.

That having been said, Russia is not going to conquer Ukraine militarily. That's not going to happen. And the Russians might gain more territory at a horrific cost, but they're not going to be conquering Ukraine. The Ukrainians are not going to surrender. I am pretty confident that the West is going to stand firm back in Ukraine, and I think the Ukrainians will regain a lot more territory over time. Then we're going to have to see. The coming weeks will be very telling because we'll see whether the Ukrainians are able to get off a counteroffensive or not and what the Russians actually do and and what actually happens.

MICHAEL MORELL: Are the Russians capable of sustaining a counter offensive for for any significant period of time?

FRED KAGAN: Yes, I know the Russians are suffering from severe limitations in material their own. Putin has not mobilized Russia fully for war. He hasn't mobilized Russian defense industry. International sanctions are badly hampering Russia's ability to mobilize its defense industry. They don't have enough tanks. They don't have enough equipment of all sorts to provide for the soldiers that they're mobilized for. They have a lot of manpower, but they're not able to give it modern equipment. They fired most of their stocks of precision weapons. They're trying to get stuff from Iran. But that's not going to be enough, I think, to give them to offset their other gaps.

And in particular, they've been suffering from shortages of artillery shells, which is a problem for them because they've been relying on each other to make gains. All of which having been said, though, Putin has reportedly has something like 325,000 troops in Ukraine now and another 150,000 training in Russia. These are very poor quality troops. They're generally demoralized. They're not skilled, but it's a lot of bodies. And I think with those bodies and Putin's continued will to fight, they can sustain these sort of World War I kind of operations that make limited gains and horrific human cost.

But I don't think that we're going to see huge operationally significant advances by the Russians, because I just don't think that they have either the training or the equipment or the supplies to make those kinds of gains.

MICHAEL MORELL: What about what about the Ukrainian ability to conduct an offensive here? How how capable are they? What more do they need? How far can they push? How far, how much can they take back?

FRED KAGAN: So as a matter of policy, we don't collect on the Ukrainians. We don't collect on the U.S. or its allies. So I can't give you an estimate with the same kind of confidence that I have about the Russians. What's very clear is that the Ukrainians have the will to continue to fight. It seems pretty clear to me that the Ukrainians are still holding back forces in hopes of conducting another counteroffensive operation. Certainly, they keep saying that they are.

What I'm concerned about is the material. They've lost a lot of tanks. They've lost a lot of armored personnel carriers, we have only just committed to giving them Western tanks, having exhausted our supply of Soviet-era stuff; the Western tanks to take a while to arrive and so on. So I don't know, but I don't know what the Ukrainian chief of staff has in his back pocket. I hope it's something and I hope that he will surprise the Russians and us with a counter-offensive soon.

MICHAEL MORELL: Okay, Fred, I want to shift gears here to another difficult issue, which is China. And I'd like to ask you how you would characterize the national security challenge that China poses to us.

FRED KAGAN: So trying to pose as many national security challenges to us – we could spend the rest of the morning talking about this. As you know, obviously, China poses an economic challenge based on on the radical policies that it has been pursuing. But in terms of pure, pure national security issues, the most immediate threat is to Taiwan, and that has been preoccupying our defense establishment, rightly so.

But I think that we run the risk of becoming too myopically focused on the problem of defending Taiwan against Chinese invasion. I also think, by the way, that we have – there's far too many comments I'm hearing with people saying very dispositively the Chinese are going to invade Taiwan in two years. The Chinese are going to invade.

MICHAEL MORELL: Right.

FRED KAGAN: I don't think it's helpful to be saying that, candidly. And for many reasons. I don't actually assess it to be accurate. And I think that our challenge is to deter the Chinese from taking any such action. And I think that that's feasible.

Here's what I'm really worried about with that, with the focus on that invasion threat. The Chinese, as I'm about to argue in a forthcoming paper that I've written with Dan Blumenthal, my colleague at AEI, the Chinese are pursuing really three roads to regaining control of Taiwan.

One is by persuasion, using information operations. Another is by coercion, using various information operations, but also the overflights, sort of military pressures and various other things. And the last would be by compellence, by force. What I'm concerned about is that if we become myopically focused on deterring or defeating the Chinese attempt to secure Taiwan by force, deter stopping them from winning by coercion is not a lesser included task.

MICHAEL MORELL: Right.

FRED KAGAN: And we have to block all three of those roads. And I'm worried that we're too focused on only one of them, even if it's certainly one that we need to be focused on.

MICHAEL MORELL: That's a really important point, Fred.

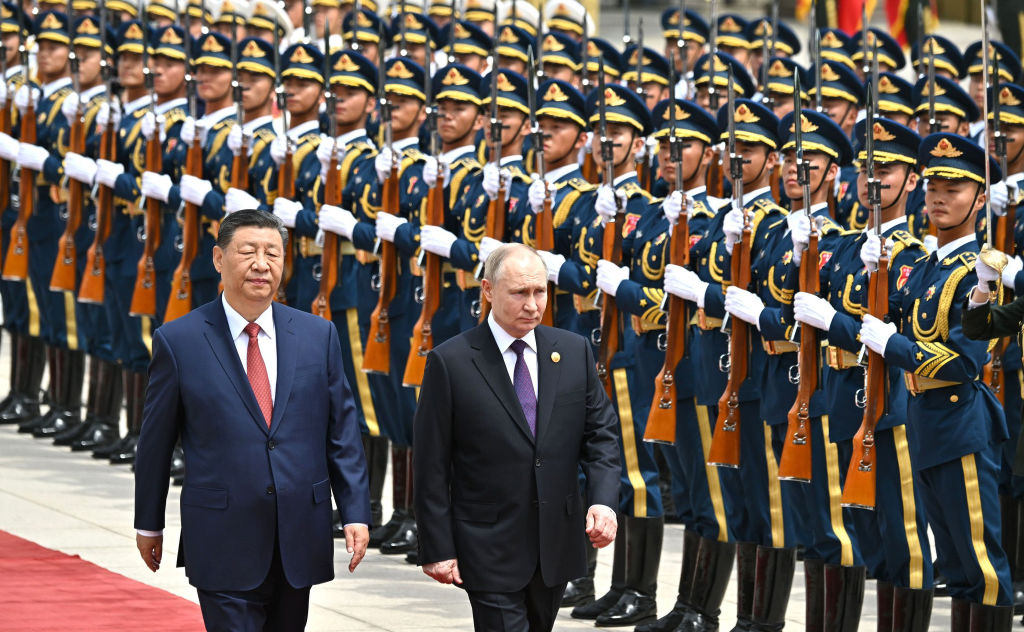

So I don't want to leave Ukraine and China, Fred, without mentioning the special relationship between Russia and China, between Xi and Putin, which is based, in my view, almost entirely on their joint desire to weaken the United States on the international stage. What I want to ask you, though, is a bit of a different question. How do you think Russian history will judge Putin and how do you think Chinese history will judge Xi?

FRED KAGAN: Well, I can't resist a quote.

MICHAEL MORELL: I couldn't resist asking the question.

FRED KAGAN: No, that's fine. And I can't resist quoting Kissinger's account of what Mao Zedong asked him when he said when he asked what he thought about the French Revolution: "It's too soon to tell."

Look, it's going to depend on whether Putin wins or loses this war. And we all have been far too quick to decide that Putin has already lost. He hasn't. If he ends this phase of this war with the battle lines anywhere close to where they are right now, it will have been a significant, if extraordinarily costly, victory for Russia and it will be portrayed as such.

If we want Putin to lose, and I think it's very important that he does lose, then the Ukrainians are going to have to liberate a lot more of their territory and we'd have to help them. So I actually think the jury's still out on that. And that's one of the reasons why Putin keeps fighting. And it's one of the reasons why he's not interested in negotiating on any serious terms right now, because he still thinks he can win.

And if I could just make this point really briefly: we're having conversations about negotiations in the West that are extraordinarily naive, including naive about how negotiations actually work, because if you want an adversary to make significant concessions, the adversary has to believe that he can't get what he wants by force. And we've told ourselves that Putin has already lost. But Putin hasn't gotten that memo. So more has to be done to make it clear to Putin that he has lost, that he can't win if there's going to be any hope of getting him to the negotiating table on any basis that anybody should be willing to accept.

But until we know what the outcome of this conflict is, we're not – I'm not going to be able to answer the question about how Putin will be judged in by Russians in Russian history.

MICHAEL MORELL: This is an extraordinarily important point, because I think most people think that Putin has already lost, right, politically and strategically. And there's no way that he can come out the other end looking any different. And I think the point you're making is extraordinarily important and needs to inform policy in the West.

FRED KAGAN: Well, I thank you. I agree. I think we need to see the world from Putin's perspective. I think there's a problem with getting too deeply into rational actor model explanations of things. From our perspective, Putin's already lost. I mean, if a U.S. president had undertaken something like this and had this kind of outcome or this kind of situation, then it would be there would have been a defeat.

But Putin has been in office for 20 years now, 22 years. He's been waging this war, as you noted, since 2014. Actually, he's been setting conditions for even longer than that. He's taking a long view here. And the territory in Ukraine that he's occupied would leave Ukraine strategically vulnerable to a future Russian attack and economically crippled. That would leave Russia in a much more advantageous position for a renewed attack in the future than it had at the start of this.

In addition to which, Putin has identified, finally, the fundamental flaws in his military that led to all of the catastrophes that we've been observing. And he is allowing his professional military staff now to start fixing those problems. We should expect Russia to reemerge as a significant threat after this phase of the war dies down, and it will be a significant threat to Ukraine. So, no, the outcome of this conflict is by no means determined yet.

MICHAEL MORELL: What about Xi? And I know you're going to say it's too early, but, you know, he's making economic policy choices that are not in the long term interests of the country. He's rolled back economic reform. He's got two very difficult challenges to deal with in terms of demographics and the debt overhang in his economy. In terms of being being repressive, he risks dampening innovation both political and and economic innovation. So he doesn't seem to be heading in the right direction here from what's in the long term interests of China. Can I just get you to react to that?

FRED KAGAN: I mean, I should caveat this by saying I'm not a China expert by any stretch of the imagination. So take all of this for for what you will.

Xi, I think, has made a fundamental bet. And the bet is that he can reassert an almost Maoist level of personal dictatorship in China of the sort that hasn't been seen really since Mao. And I think that for me, the whole prism of how Xi will be seen has to focus on that bet that he's made with himself. If having done that and having increasingly imposed one man rule back on a system that had been somewhat - I don't want to overstate this, but somewhat more oligarchic than that - if he wins major triumphs for China and brings the Chinese Communist Party to a new position of strength, then he may go down relatively well.

But as you say, the trend lines don't look very good for those things to happen. And I think the danger to his reputation comes from having paid this bet to begin with. That makes the stakes for him much higher in all of the activities that he's pursuing.

His mishandling of the COVID crisis is very significant and very telling. His reaction to his realization that he'd mishandled it is also very interesting, the chaotic and unplanned backing away from the zero-COVID policy really raises some very interesting questions about what he thought was going on, what his theory of the case had been and what people were telling him. So I think the situation is quite fraught for him, honestly.

MICHAEL MORELL: I'm going to take you to North Korea, quickly. The growth of North Korea's strategic weapons programs continues. Kim's focused on enhancing his arsenal of ballistic missiles, strategic nuclear weapons, and now even even tactical nuclear weapons. And I'm wondering if you're more worried about this place than you were five years ago.

These tactical nuclear weapons worry me in a way that I wasn't worried before because it suggests that he perhaps sees some need to use them, that he has some options here that perhaps we didn't think he had. Let me just get your reaction to how how concerned you are.

FRED KAGAN: I am concerned, but I would just take a step back. I can say, look, if you think back to the whole discussion and policies that we had in the 1990s as the North Koreans were developing this program and we were debating various options, we chose an option that permitted this proliferation. We had a lot of explanations for ourselves at the time about why that was okay and why that was the better thing to do.

It's really not clear to me over the long term that those were the best choices. And I think as we look at other proliferation scenarios around the world, we really need to consider the lessons that should be drawn here. Because if North Korea didn't have nuclear weapons right now, I wouldn't be very worried about North Korea.

MICHAEL MORELL: Right.

FRED KAGAN: It does. I am very worried about it. And I'm also worried about it as a potential proliferator in various other ways. And we have plenty of evidence to think that they might or that they have, in fact, engaged in activities to assist other states with nuclear weapons programs. So I'm alarmed about this in many dimensions, but I think it really should inform our thinking about how comfortable we actually are with nuclear proliferation in general.

MICHAEL MORELL: And to your point about proliferation, North Korea has sold every other military technology that it ever developed.

FRED KAGAN: Exactly.

MICHAEL MORELL: So deep concern there.

So great transition to Iran. This is one of the countries that you noted that you follow closely in your Critical Threat Project. And I really want to ask two questions, Fred, about Iran. The first is, are we losing the battle? Have we lost the battle of preventing Iran from ultimately becoming a nuclear weapon state?

FRED KAGAN: Well, we haven't lost it in the sense that Iran is not yet a nuclear weapon state. We've lost it in the sense that I don't think that there is a way to prevent Iran from becoming a nuclear weapon state that doesn't involve a very significant military operation. And even that, I think, is would be dicey in its own right in many ways. And I'm not advocating it. But even that is questionable in its ability to stop them. So I think we're in a very, very bad situation.

President Obama had developed a theory for how we were going to stop this from happening, which was the nuclear deal. I think it was a very flawed theory, but it was a theory and we were pursuing it for many years.

President Trump chose to withdraw from the deal. I thought that that was a mistake for various reasons. But he attempted then to develop an alternative strategy for containing Iran.

President Biden, as far as I can tell, the only policy toward Iran that he has had was getting back into the nuclear deal. That policy has failed, and the administration seems to have recognized that it's failed. But I haven't heard from the administration any articulation of any alternative strategy for Iran, for the nuclear program or anything else. And this is a matter of great concern to me, because it's okay to come in with an idea about what you want to do. It's good for administration to do that . It's also good to recognize when it's not going to work great. But then you have to have a new idea.

MICHAEL MORELL: Yeah.

FRED KAGAN: And I don't see one out there. And I find that extremely alarming.

MICHAEL MORELL: And they are right there. They are getting very close to what we in the intelligence community talk about in terms of threshold, right. Having the pieces and being able to put them together very quickly. They're still not there, but they're getting very close to that. And once they're there, it's very difficult to roll that back.

FRED KAGAN: Yeah. And I think the part of the question is, there are a bunch of decisions, as you know, that Khamenei will need to make. What kind of nuclear state does he want to be? Does he want to be a nuclear state with a bomb or two that he might be able to put in a container on a ship and get into the port in Tel Aviv and like that? Because if he wants to that he could probably do that very quickly.

My assessment of this has always been that that actually isn't what he wants. That Iran doesn't want to become a nuclear state like North Korea. It wants to become a nuclear state like Israel. It wants to become a nuclear state like Pakistan, because the enrichment infrastructure the Iranians have always been trying to build seems to me to have been designed to support a nuclear arsenal, not a nuclear bomb. And that can affect the Iranian calculation about how rapidly they move to what levels of breakout.

However, on the other side of that, there's a risk calculation that they have to make about at what point they think that they are facing potential threat of some kind of activity that they would want to deter that might cause them to raise to the lower threshold breakout. Bottom line is, we're in a very, very bad place when fundamentally the decision rests with Khamenei about what kind of nuclear power Iran wants Iran to be rather than about whether Iran can be a nuclear power. And unfortunately, I do think that that's where we are right now.

MICHAEL MORELL: I think the other interesting point here is that he has been firmly in charge and firmly making the decisions about this program. And I think you're absolutely right about the direction he wanted to go. But at some point, he leaves the scene. And we have a new Supreme Leader or we have a new, you know, political order in Iran. And there are debates in Iran about what their nuclear weapons policy should be. So all of this could change dramatically when he leaves the scene.

FRED KAGAN: Yes. And one of the reasons why we started doing daily updates back in September was that he had a bad health scare that clearly persuaded a lot of senior people in the regime that he was imminently dying. He didn't turn out to be. But that has really kicked the succession question into high gear in Iran.

And listen, here's one thing that I'm really pretty confident in assessing or forecasting: the next Supreme Leader, whenever that comes, and I suspect it will be sooner rather than later, the next Supreme Leader will probably have less ability to control the IRGC's desire for much more aggressive policy and strategy across the board than Khamenei did.

Depending on who you think the next Supreme leader is, he may not want to. But Khamenei will have been Supreme Leader for more than 30 years. His death will be an epochal event in Iran. There is no one on the scene in Iran who has anything remotely approaching his stature. And so the next Supreme Leader will be much more vulnerable to Guard pressure if he tries to push back or having to demonstrate his pliability to the Guard to get the Guard on side if he is not already a Guard pick.

That, to me is extremely alarming, because for all of his many flaws and we could spend days listing his flaws, Khamenei has been a relatively cautious and conservative figure who has reined the Guard in on many occasions. So I am very concerned that a succession in Iran is very likely to produce a situation in which Iranian foreign policy, military policy and nuclear policy gets unleashed in a certain way that could be extremely destabilizing and could also have important and very worrisome implications for the Iranian nuclear program.

MICHAEL MORELL: Fred, how do you guys think about the most recent protests in Iran?

FRED KAGAN: We think this protest movement is the most significant in the history of the Islamic Republic. It certainly has lasted longer than any other. It has strained the Iranian security forces. And although the protests have, for the most part, died down, they have done so on the Iranian people's terms. The protests were not crushed by the regime. That's not why they stopped. Neither did the regime make any concessions. On the contrary, the regime has been pushing ever harder in the direction of exacerbating the grievances that started these protests to begin with.

Fundamentally, our assessment is the Iranian people became tired and found the normal economic imperatives that humans have that make it hard to continue protesting indefinitely. But people stopped protesting because they chose to stop protesting, not because they were compelled to or because they've been persuaded.

And more than that, we have been closely monitoring and observing the emergence of visible protest organizers online, some of whom we've been able to show actually are able to generate protest activity. All of those groups are still present and active. So this protest ended with a much more visible and highly organized anti-regime structure than we've ever seen before. So all of that, I think, bodes well for the renewal of anti-regime activity in the coming days, weeks or months. And it bodes very ill for stability in the regime, as we just published in the update that you could find, at criticalthreats.org, we think that there are some senior officials in the regime who understand this. People like former President Rouhani, like parliamentary speaker Ghalibaf, even like the Supreme National Security Committee Secretary Ali Shamkhani, the latter of two of whom are unquestionably hardliners, but also relatively pragmatic.

And they have been messaging that they are very concerned. They think that the regime has lost the people. We agree with that assessment. And they are clearly signaling that they think the policies that the regime is following are not going to win the people back. And we agree with that assessment.

So I think that we have are moving through an inflection here that could very well be bringing us into the beginning of the end of the Islamic Republic. I don't want to give you a timeline for that or tell you how that happens, but I think this is a very, very serious situation for the Islamic Republic. And I think that there's reason for some optimism that the days of this vicious regime may be beginning to draw to a close.

MICHAEL MORELL: We have literally one minute left here. And I wanted to ask you about about terrorism. But I'm going to ask you another question. I know you're very proud of your team, very proud of the people that you work with. You don't do this by yourself. And I wanted to give you an opportunity to say something about them.

FRED KAGAN: What you're hearing from me are the assessments that are based on the phenomenal work that our brilliant young analysts do every day at great sacrifice. I love them. I am unbelievably proud of them. And it is such a privilege to be able to engage with young Americans who are so committed to American interests and values and who are so brilliant and able to find ways of bringing these kinds of assessments and forecasts out of publicly available information on tiny teams with limited resources. I just, I can't praise enough the teams at the Critical Threats Project and the Institute for the Study of War, with which we're partnered. I'm grateful to be able to work with them every day.

MICHAEL MORELL:

Fred, thank you so much for joining us this morning.

FRED KAGAN: Thank you for having me.