Thomas Starzl, liver transplant surgical pioneer, dead at 90

PITTSBURGH -- Dr. Thomas Starzl, who pioneered liver transplant surgery in the 1960s and was a leading researcher into anti-rejection drugs, has died. He was 90.

The University of Pittsburgh, speaking on behalf of Starzl's family, said the renowned doctor died Saturday at his home in Pittsburgh.

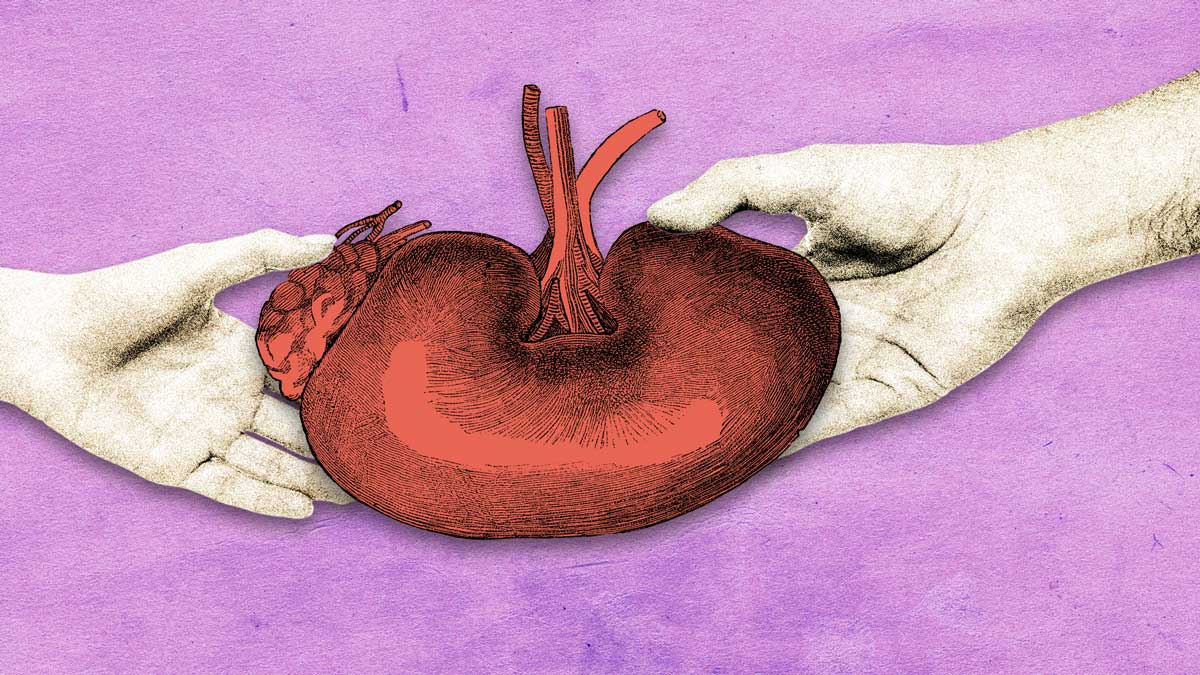

Starzl performed the world's first liver transplant in 1963 and the world's first successful liver transplant in 1967, and pioneered kidney transplantation from cadavers. He later perfected the process by using identical twins and, eventually, other blood relatives as donors.

Since Starzl's first successful liver transplant, thousands of lives have been saved by similar operations.

"We regard him as the father of transplantation," said Dr. Abhinav Humar, clinical director of the Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute. "His legacy in transplantation is hard to put into words - it's really immense."

Starzl joined the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine in 1981 as professor of surgery, where his studies on the anti-rejection drug cyclosporin transformed transplantation from an experimental procedure into one that gave patients a hope they could survive an otherwise fatal organ failure.

It was Starzl's development of cyclosporin in combination with steroids that offered a solution to organ rejection.

Until 1991, Starzl served as chief of transplant services at UPMC, then was named director of the University of Pittsburgh Transplantation Institute, where he continued research on a process he called chimerism, based on a 1992 paper he wrote on the theory that new organs and old bodies "learn" to co-exist without immunosupression drugs.

The institute was renamed in Starzl's honor in 1996, and he continued as its director.

In his 1992 autobiography, "The Puzzle People: Memoirs of a Transplant Surgeon," Starzl said he actually hated performing surgery and was sickened with fear each time he prepared for an operation.

"I was striving for liberation my whole life," he said in an interview.

Starzl's career-long interest in research began with a liver operation he assisted on while a resident at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. After the surgery to redirect blood flow around the liver, he noticed the patient's sugar diabetes also had improved.

Thinking he had found the cause of diabetes to be in the liver rather than the pancreas, he designed experiments in 1956 with dogs to prove his discovery. He was wrong, but had started on the path that would lead to the first human liver transplants at the University of Colorado in Denver seven years later.

In the early 1990s, livers from baboons were transplanted into humans, an operation made possible by Starzl's research into alternatives to scarce human livers. While work continues on such animal-to-human transplants, most researchers now focus on pigs rather than primates and use genetic engineering to try to knock out some proteins most involved in causing acute rejection, Humar said.

Starzl's other accomplishments included inventing a way to route the blood supply around the liver during surgery to make possible the marathon hours required to complete operations involving that complex organ.

He also showed that "soldier cells" from the transplanted organ become "missionary cells" that travel throughout the new body and find new homes, apparently helping the body accept the foreign organ.

Starzl helped develop with Dr. John Fung, his protege at UPMC and successor as director of transplant surgery, the use of the experimental anti-rejection drug FK506, which paved the way to more complicated transplants of multiple organs, including the difficult small intestine. FK506 was discovered in a soil sample by Japanese researchers.

In September 1990, at age 65, Starzl put away his scalpel for good, soon after the death of a famous young patient: a 14-year-old girl from White Settlement, Texas, named Stormie Jones. Starzl also underwent a heart bypass operation in 1990 and suffered lingering vision problems from a laser accident five years earlier.

Stormie lived six years after a combination heart-liver transplant at age 8 but needed a second liver in 1990 and died within nine months. Her death affected Starzl greatly.

"It is true that transplant surgeons saved patients, but the patients rescued us in turn and gave meaning to what we did, or tried to," he once wrote.

Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald called Starzl "a true Pittsburgh icon and hero," whose research had worldwide impact and had proven an economic boon to the region as well.

"The number of lives which were, and continue to be transformed, by Dr. Starzl's groundbreaking work are immeasurable," he said.

Starzl was born March 11, 1926, in LeMars, Iowa. His mother was a nurse and his father was a science fiction writer and the publisher of the local newspaper. Starzl's uncle, the late Frank Starzel, was general manager of the Associated Press from 1948 to 1962.

Starzl is survived by his wife of 36 years, Joy Starzl, his son, Timothy, and a grandchild.

In a statement on Sunday, his family described him as "a pioneer, a legend, a great human, and a great humanitarian."

"He was a force of nature that swept all those around him into his orbit, challenging those that surrounded him to strive to match his superhuman feats of focus, will and compassion," his family said. "His work in neuroscience, metabolism, transplantation and immunology has brought life and hope to countless patients, and his teaching in these areas has spread that capacity for good to countless practitioners and researchers everywhere."

Patrick Gallagher, chancellor at the University of Pittsburgh, said Starzl "was a man of unsurpassed intellect, passion and courage whose work opened up a new frontier in science and forever changed modern medicine."

"He will be remembered for many things, but perhaps most importantly for the countless lives he saved through his pioneering work," Gallagher said in a statement.