Thomas Jefferson, architect

Thomas Jefferson was many things – politician and diplomat, naturalist and scientist. Revered as America's third president, he was also the main author of the Declaration of Independence. What's less well-known is his role as an architect who helped shape the look of early America.

That side of Jefferson is getting special attention at the moment with an exhibition at the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia. It illustrates both the brilliance of his vision and what, to many, is an unforgivable blind spot.

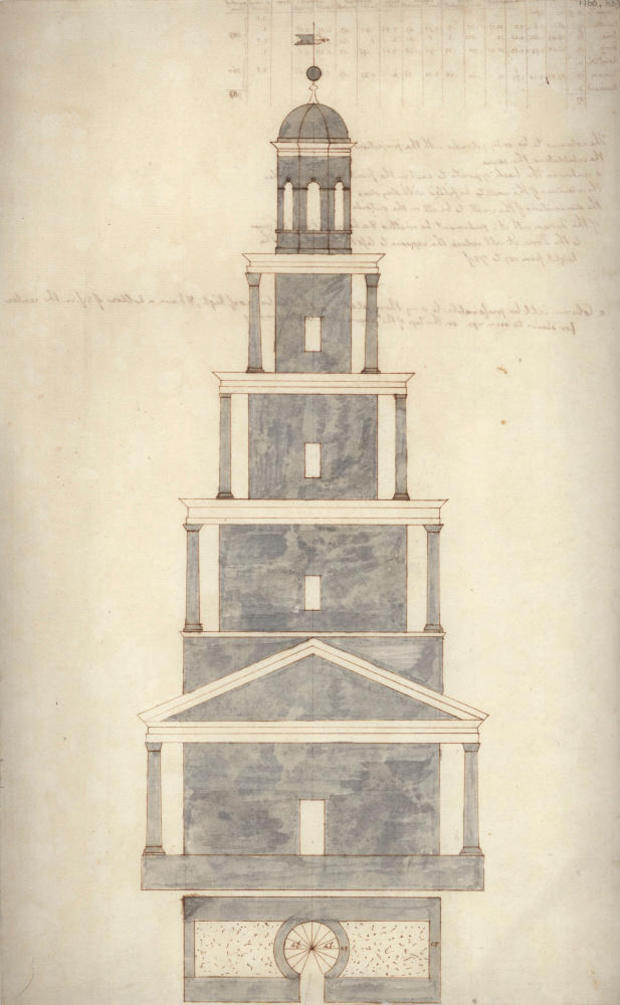

The title of the show is "Thomas Jefferson, Architect." Though not a professional architect, he was, said curator and museum director Erik Neil, "one of the most advanced architectural thinkers of his time."

Neil said evidence of Jefferson's influence is how familiar his designs now look. Examining one architectural model, correspondent Brook Silva-Braga said, "This is almost like a cliché of a government building now."

"It wasn't then," said Neil. "Jefferson was saying, 'We want to do, like, what the Ancient Romans and what the Ancient Greeks did, because they had the highest form of government and the legislators acted with wisdom.'"

The architecture, he felt, should convey that.

Jefferson's plantation home, Monticello, carried those principles; so did his anonymous submission to a design competition for the White House, which featured a large dome.

"This dome was to have glass windows," said Neil. "It was the most innovative. It was the most advanced. I'm not sure if it actually could've been built."

These models first appeared at an Italian retrospective on Jefferson's architecture. Neil saw that show and wanted to bring it home to Virginia, but realized that was a complicated idea.

Silva-Braga asked, "Would it be going too far to say that you thought that exhibition wouldn't be well-received here?"

"It wouldn't be enough," Neil replied. "If I had presented that exhibition, I would have rightly been criticized."

Jefferson's designs, after all, were made into buildings by slaves.

As a politician he helped end the Atlantic slave trade, but at Monticello and elsewhere, Jefferson owned more than 600 human beings, including his mistress, Sally Hemings.

So, Neil enlisted a diverse group of advisors to make a new kind of exhibit, highlighting the otherwise anonymous people who built things, like a paneled door made at Monticello.

"They've been able to analyze the grain and the grooves, and the details of the door, and connect that to a set of tools that are known to have been John Hemmings'," said Neil.

John Hemmings was Sally Hemings' brother

There is a brick under glass, next to a handful of handmade nails as a tribute to Isaac Granger, one of the men who made Jefferson's nails. In a daguerreotype taken c. 1847, Granger is pictured wearing his workman's apron.

Love it or hate it, the exhibit is a profoundly different way to present Jefferson.

Silva-Braga asked, "I could see people saying, 'This is an American hero; why are you trying to bring him down?' I could see people saying, 'This is a slaveholder; why are you still building him up?'"

"I've gotten a couple letters: 'How could you do this to Thomas Jefferson? Why would you tarnish the image of this great man?'" said Neil. "And I've had other people say, 'Really? We want to give praise to this man who really had a concubine, who had a slave mistress?'"

The reassessment of Jefferson the architect will continue this spring at the University of Virginia, a campus he designed, when UVA dedicates a "memorial to enslaved laborers."

Columbia University professor Mabel Wilson worked on the UVA memorial and the Chrysler Museum exhibit. She studies architecture and race, and says one of Jefferson's hallmarks was hiding the places where slaves lived and worked.

"I think this is what makes him an architect," she said, "that he understands that the buildings make relationships between people. So, he is very shrewd at using architecture to make invisible something that he completely understood was morally reprehensible and against the values of freedom and equality."

This is all part of a larger reckoning in Virginia.

Janice Underwood is Virginia's first-ever director of diversity, equity and inclusion, hired by Governor Ralph Northam after a photo of a man in blackface was found on Northam's yearbook page. [Virginia's second governor was Thomas Jefferson, who designed the Capitol building where Underwood now works.]

"He said that all men are created equal," Underwood said. "And while I know that to be true, he would not have included me in that. He would not have included Sally Hemings in that, or any of his children with Sally Hemings."

Underwood says she isn't sure if the statue of Jefferson just behind the Capitol should even stay up.

"I don't know, we're reckoning with those questions now," she said. "For so long, we've only told one side of the story."

A handful of other museums across the country are making a similar shift, in some cases changing the labels next to paintings to explain that the person in the portrait was involved in the slave trade.

In its way, the Chrysler Museum is attempting answers to the questions that surround Jefferson, by teaching new names, and attaching new meaning to old ones.

Silva-Braga asked, "Do you want them to come away with the idea that Thomas Jefferson was a great American, or maybe just an important American?"

"I would say he's a great American," Neil replied. "I would say the idea that we have a president who has ideals that we still aspire to, is really something I want people to take away with them. To recognize he fell short of his aspirations, I hope they come away with that as well."

For more info:

- Thomas Jefferson, Architect: Palladian Models, Democratic Principles, and the Conflict of Ideals, at the Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Va. (through January 19)