The Texas yogurt shop murders: Families, investigators remain haunted by unsolved case

CASE UPDATE: In September 2025, the Austin Police Department identified Robert Eugene Brashers, a serial killer and rapist, as the suspect in the Yogurt Shop murders. Brashers, who is deceased, was tied to the murders through DNA testing. In December 2025, the Travis County D.A.'s office filed a motion to begin the process of exonerating the four men who were wrongfully accused of the murders.

This story previously aired on Aug. 27, 2022.

More than three decades ago, four teenage girls were brutally murdered in an I Can't Believe It's Yogurt! shop in Austin, Texas. The horrific crime has haunted their families, the city, and the investigators who chased every lead in the case to a dead end. Could new information finally help solve the case?

"I can see them, I can still see the inside of that place," John Jones, the first investigator on the case, tells "48 Hours" correspondent Erin Moriarty. "That stuff's … indelibly burned in my mind."

The story starts on Dec. 6, 1991, when Eliza Thomas, Sarah and Jennifer Harbison and Amy Ayers were tied up and shot. The yogurt shop was then set on fire. For decades, investigators worked to find suspects. There were eventually arrests and even convictions. But those convictions were overturned, leaving the case unsolved today.

"There is a kind of torture that continues by the fact that it's unsolved and it's ongoing," says Sonora Thomas, who was 13 when her sister Eliza was killed.

"It's always there," says Jones.

There may be some positive news, however. A small sample of male DNA was found on one of the victims. With DNA research advancing, investigators hope there will be a match that solves the case.

"Do you believe that there is right now, some evidence that could lead to the killers?" Moriarty asks Texas defense attorney Joe James Sawyer.

"Yes," Sawyer says.

"Is this the end of the beginning or the beginning of the end?" Jones asks.

THE SEARCH FOR ANSWERS

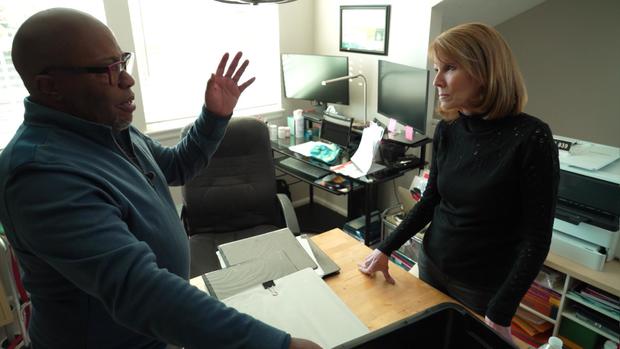

It's been more than 30 years since John Jones began the painstaking search for the killers of four teenage girls in an Austin, Texas, yogurt shop.

He has long since retired from the Austin Police Department and moved out of Texas. But copies of some of the case files moved with him.

Erin Moriarty [with Jones in his home office]: What is all of this here?

John Jones: These are my notes. … Oh, that's the big book … this one is really from day 1 … hypnosis, polygraph, confessions.

Erin Moriarty: (picks up coffee mug) You know, I notice this sitting here.

John Jones: Yeah.

Erin Moriarty (reads coffee mug): "We will not forget." You haven't.

John Jones: Nope. I can't.

The images of Dec. 6, 1991, remain all too vivid.

John Jones: I can definitely still see it.

It started with that call from dispatch to go to a scene of a fire, that would turn into something far worse:

JOHN JONES: What do you'll got out there? I'm en route … airport 35.

DISPATCH: We've got a fire …

JOHN JONES (1991 on radio): OK. I'm copying the fire part, but you cut out on the first part of that though.

DISPATCH: … apparently a robbery and homicide. There's, uh, three fatalities.

JOHN JONES: That's 10-4, we're en route (turns on siren).

John Jones: And then about halfway out there, they call again on the radio and said we found a fourth body.

A local TV news crew happened to be filming Jones on a ride along that night.

JOHN JONES (on radio): What place of business is this at?

DISPATCH: It's the I Can't Believe It's Yogurt.

JOHN JONES: OK.

John Jones: The fire department had just knocked down the fire. … there was still a lot of water in there … a lot of smoke still. … it was all muted grays, blacks there was no color in there with the exception of the girls.

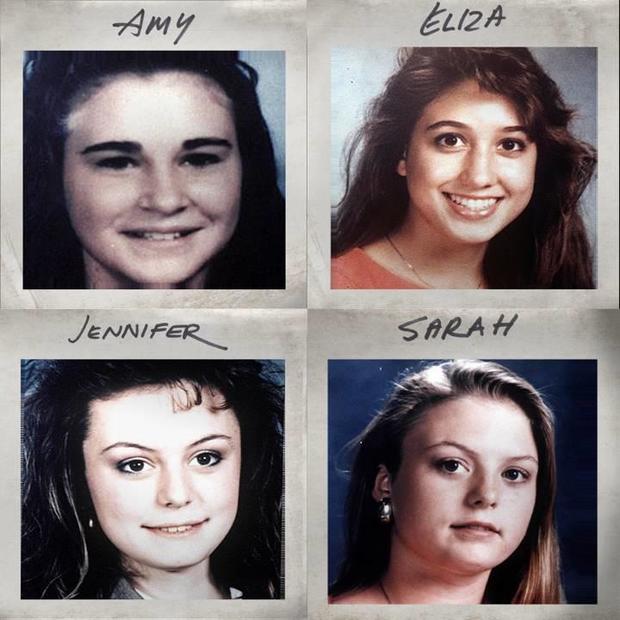

The girls were quickly identified. Two had been working at the shop, closing up that night: Eliza Thomas and Jennifer Harbison were both 17 years old. Jennifer's 15-year-old sister, Sarah, and their friend, 13-year-old Amy Ayers, had met them there to head home.

The four girls had been gagged, tied up with their own clothing, and shot in the head. Investigators would learn at least one of the victims had been sexually assaulted. The yogurt shop had also been set on fire, destroying potential evidence.

John Jones: There was smoke and soot on every surface, kind of made fingerprinting kind of difficult.

This was a crime like none Austin had seen before. Jones knew he needed help, and from the scene, contacted the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, The FBI, and Texas Department of Public Safety.

John Jones: As soon as we knew what type of guns we were looking for, that information went out nationwide.

Gunshot wounds showed that two different types of guns were used, leading investigators to believe there were at least two killers on the loose.

Erin Moriarty: What were the two guns?

John Jones: .380 and a .22. … And we recovered all of the rounds.

The weapons, though, were not found, and a task force worked to come up with potential suspects.

John Jones: They were from all spectrums. I mean, we looked at everybody from family members to drifters.

And while police tracked down leads, the families and the City of Austin grieved.

The Harbison family lost their only children: daughters Jennifer, a hard-working high school senior, and Sarah, who was enjoying sports and clubs as a high school freshman. Their mother, Barbara, spoke with "48 Hours" in 1992.

Barbara Harbison: My life was focused around them from here to eternity. Someone took eternity away from me.

Bob Ayers is the father of the youngest victim, Amy, a country girl with a love for animals.

Bob Ayers: I lost my daughter. I lost my first dance. … I won't see her graduate. I won't see her become a veterinarian. … She was a Daddy's girl.

Sonora Thomas, 13 years old when her only sibling, Eliza, was murdered, had a hard time dealing with the loss of the sister she looked up to.

Sonora Thomas: I remember the shock … I remember fantasizing for days that my sister had somehow escaped and run away and … she was going to come back … And so that's what I was kind of holding onto.

Her parents struggled as well.

Sonora Thomas: My family never talked about my sister after she died.

Erin Moriarty: Never?

Sonora Thomas: No. It's too, it's too painful.

Sonora did as best she could, picking up some pieces of her sister's life. Eliza, an animal lover, had a pig she planned to enter in livestock show. Just a few months after the murders, Sonora took over those duties.

While Sonora may have seemed to be coping, the reality, she says, was far different.

Erin Moriarty: You had to grow up quickly.

Sonora Thomas: Very quickly … I would say I fell apart under that pressure.

John Jones: We knew they were hurting because, you know, we were hurting too.

Jones, a parent himself, felt the families' grief. He promised to do all he could to help them.

John Jones: We told them what we could. And … I assured them that we would keep them apprised as to everything that was happening, and we did.

Jones also made a pledge to the families involving the shirt he wore on the night of the murders.

John Jones: I kind of made a promise to them … that the next time they saw me with that green and white shirt on that that was a signal to them that, you know, we knew who did it.

And Jones seemed assured they would find the killers.

John Jones: We stayed in constant contact with the behavioral science unit at the FBI in Quantico … they said that I should, as the face of the investigation, I should project an air of confidence … that would cause the bad guy to shiver in his boots. … So look in the camera and be confident.

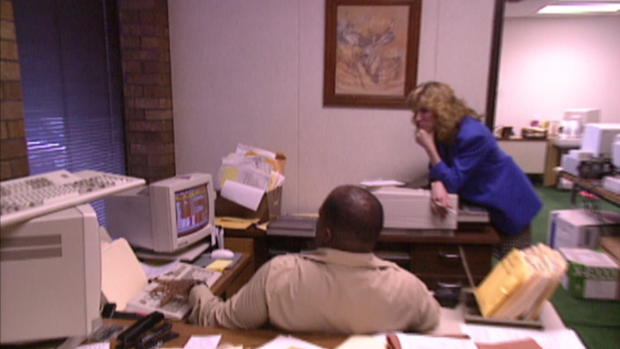

And, when we followed him working the case in 1992, he did just that.

JOHN JONES: Let me just say this, whoever you are out there, you are going to be mine one of these days….

But trying to figure that out was daunting.

John Jones (at police station in 1992): 342 people that have been listed as suspects, but we're looking at pages and pages of suspects here.

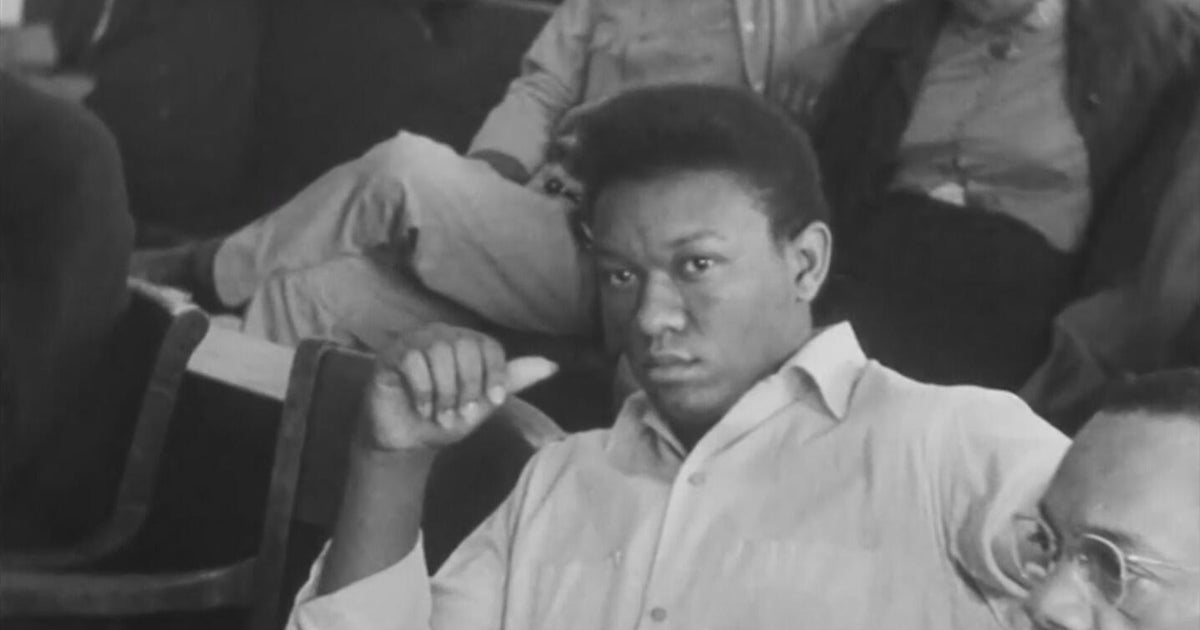

One of those early suspects was a teenager named Maurice Pierce. He was arrested eight days after the murders at a mall near the yogurt shop, carrying a .22 caliber gun, the type used in the murders.

John Jones: The .22s were unmatchable.

Erin Moriarty: So, you can't say it wasn't his gun? But there was no way to match it.

John Jones: No.

Erin Moriarty: But there was no way to match it.

John Jones: — to prove that it was his gun. He gave a statement, matter of fact, I took his statement. And he implicated three other boys.

Jones says Maurice Pierce claimed he was driving a getaway car and that three acquaintances, Forrest Welborn, Michael Scott and Robert Springsteen, were involved in the murders. But Pierce's story began to fall apart.

John Jones: It started to crater when we wired him up to go talk to Forest. And we were listening in on the wire, and it was pretty obvious Forest didn't know what Maurice was talking about.

And when Welborn, Scott and Springsteen were brought in for questioning, they too denied any involvement. It was decided there was not enough evidence to charge them and the search for other suspects continued.

CHASING LEADS

Two months after the yogurt shop murders, with no viable suspects, police were chasing leads — no matter where it took them.

The task force became aware of a counter-culture type group of local residents known to be into the supernatural.

DET. MIKE HUCKABAY [at roundtable, 1992]: They're into vampires, the occult, graveyard rites. … They go out and dance and take pictures on tombstones.

And investigators began to hear that this group might be connected to something far more serious.

John Jones (2021): The — the tips were that they were talking about the murders.

Erin Moriarty: Talking about the yogurt shop murders.

John Jones: The yogurt shop murders, yes.

There was one woman in particular whose name kept coming up in connection with these tips. The task force planned a raid on her home, hoping to see if any evidence might be found there.

John Jones: It was creepy in there.

John Jones: But as it turns out, a lot of that stuff was rat bones and theatrical parts. But … it was a good lead. … Till we finally figured out that, uh, they're just living a make-believe life (shaking his head).

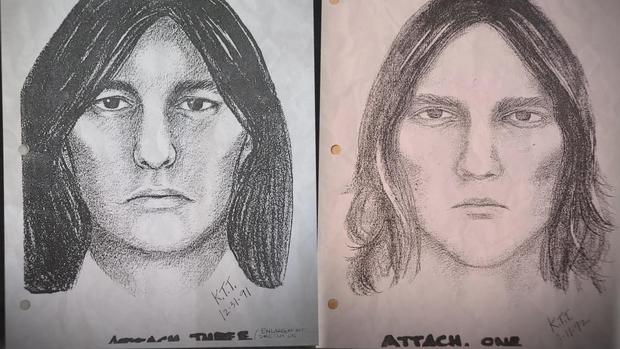

The raid may have been a bust, but it wasn't long before the task force had its eyes on another person of interest. A police sketch shows a man that multiple eyewitnesses told police they saw sitting in a car outside the yogurt shop on the night of the murders.

John Jones: And it was somebody we really wanted to talk to. … So, we put it out there.

And the response they got came from an unexpected source.

John Jones: A couple of other investigators from the Sex Crimes Unit came up and go … "We have a sketch that looks just like that."

Three weeks before the yogurt shop murders, a young woman in Austin had been kidnapped and sexually assaulted. Police had released a sketch of three men wanted in connection with that crime. One of those suspects bore a striking resemblance to that man witnesses reported sitting in a car outside the yogurt shop.

John Jones: You know, I just kind of went zip when I saw the — the composite.

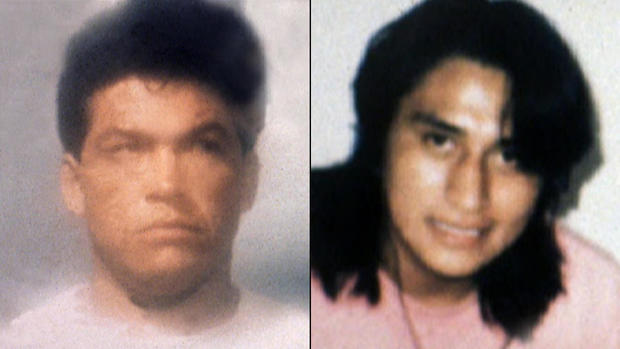

A tip came in that the men wanted in the kidnapping and sexual assault case had fled to Mexico. Two were caught and arrested; one who resembled the person of interest in the yogurt shop sketch. The development made national news.

John Jones: When they got caught in Mexico, we went down there ... to interview them. Jones' team questioned the men. And so, too, did the Mexican authorities.

John Jones: But the Mexican government … announced to the whole world that … they confessed, and they were going to try them for the murders down there.

Erin Moriarty: They confessed to the yogurt shop murders?

John Jones: Yes, they did.

But Jones learned those confessions had details that didn't match the crime scene. Even the caliber of guns they claimed to use was wrong.

John Jones: There were too many inconsistencies in the … confession.

So, Jones' team reinterviewed the men, and he says this time they recanted just about everything. It made Jones and the other investigators wonder if those confessions were coerced by the Mexican authorities. The once promising lead fell apart .

John Jones: (exhales) It was depressing.

Over the following years, there would be other confessions, ones that were willingly given.

John Jones: You know, we faced six confessions.

Erin Moriarty: Six people who confessed?

John Jones: Yeah. Written.

Erin Moriarty: That confessed to this crime?

John Jones: Yes, they did.

Erin Moriarty: And they didn't do it?

John Jones: Nope.

In 1994, after nearly three years of leading the investigation, John Jones was moved out of the homicide division. He says it was a mutual decision. Austin Police wanted fresh eyes working the case, and Jones felt it was time to move on. Other detectives took over and, as time passed, the victims' families were left wondering why no one had been arrested. Amy Ayers' mother Pam spoke to "48 Hours" in 1996.

Pam Ayers [fighting back tears]: They're probably out there leading a life as normal as they've ever had. And ours is never going to be the same.

That same year, Eliza Thomas' mom moved away from Austin … and the painful reminders.

Maria Thomas (1996): Running into people who were constantly asking how the case was going was very hard on me, and especially my daughter Sonora.

Sonora's life had taken a downward spiral.

Sonora Thomas: In my high school years, things really deteriorated. … Drugs, using alcohol, being hospitalized, going to a boarding school for, you know, disturbed teenagers, things like that.

The case seemed stalled, until October 1999.

RADIO NEWS REPORT: Some breaking news — Austin police have arrested four men in connection with the yogurt shop murders of 1991.

There were finally arrests, but would it answer the question on the billboard that had been haunting Austin for nearly a decade?

SUSPECTS ARRESTED

NEWS REPORT: After nearly eight years, Austinites are getting some answers in the case of the yogurt shop murders…

MAYOR KIRK WATSON (at 1999 press conference): I want to start off by thanking y'all for joining us here today. … For almost eight years, we've all waited to hear the words that our police department is close to a point of solving a crime that has haunted our very souls. … Today, we finally get to hear those words.

When four men were arrested in the fall of 1999 for the yogurt shop murders, relief was felt citywide.

MAYOR KIRK WATSON (at press conference): Sarah, Jennifer, Amy, Eliza, we did not forget.

The girls' families struggled to take it all in.

Sonora Thomas: There had been so many false leads for such a long time. It was hard to know how to think about it and how to feel about it.

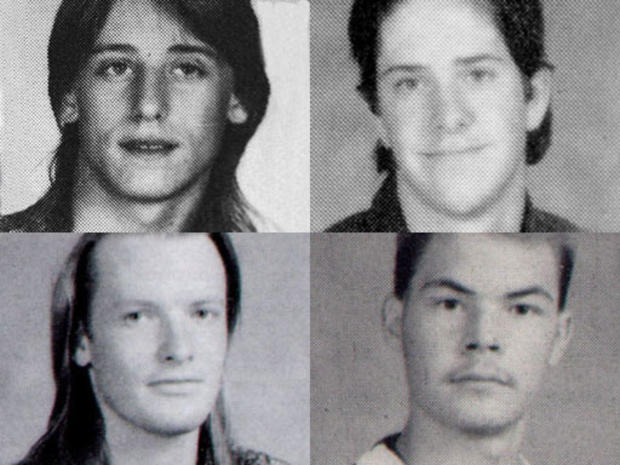

But there were finally names and faces to blame: Maurice Pierce, Forrest Welborn, Michael Scott and Robert Springsteen. To the task force, they were familiar names and faces. They were the same young men that John Jones and his investigators questioned just eight days after the murders and ultimately released for lack of evidence.

John Jones: I was confident and remain confident to this day that we got as far with them as we could then. But that doesn't mean that … there wasn't something developed later that would cause them to actually go out and arrest them. So, I was going, "yes, good job." … I was ready to dig out the hideous green and white shirt.

But before that shirt could come out of the closet—the one he promised the girls' families he would wear when the case was solved — Jones wanted to know more about what led to the arrests.

Joe James Sawyer: There was no physical evidence. Nothing.

Joe James Sawyer was appointed as Robert Springsteen's attorney.

Erin Moriarty: What made them go back and charge these guys?

Joe James Sawyer: Because the new officers, when they reopened the cold case, convinced themselves that "we let them slip through our fingers. We had to have had the murderers in the beginning." In part, they decided that because they had nothing else.

There was no new physical evidence suddenly tying any of the four men to the crime, but what police did have were two newly obtained confessions— one from Michael Scott and another from Sawyer's own client, Robert Springsteen. Michael Scott's confession came first. He was questioned over four days:

OFFICER (1999 interrogation): Come on Michael, you're doing good. Tell us. Let's do this today. Let's do it.

MICHAEL SCOTT: I remember seeing girls. … I remember one girl screaming, terrified.

Scott told investigators that he and the others only intended a simple robbery. He said they cased the yogurt shop earlier that day. And then, after dark, he said, they came back armed with two guns.

MICHAEL SCOTT (interrogation): I hear the gun go off. I only pulled the trigger once…. I hear another gun go off.

Investigators claimed that Springsteen later corroborated much of what Scott said. But after intense questioning, he went further.

OFFICER (interrogation): You f------g know if you f------g raped her, just say it.

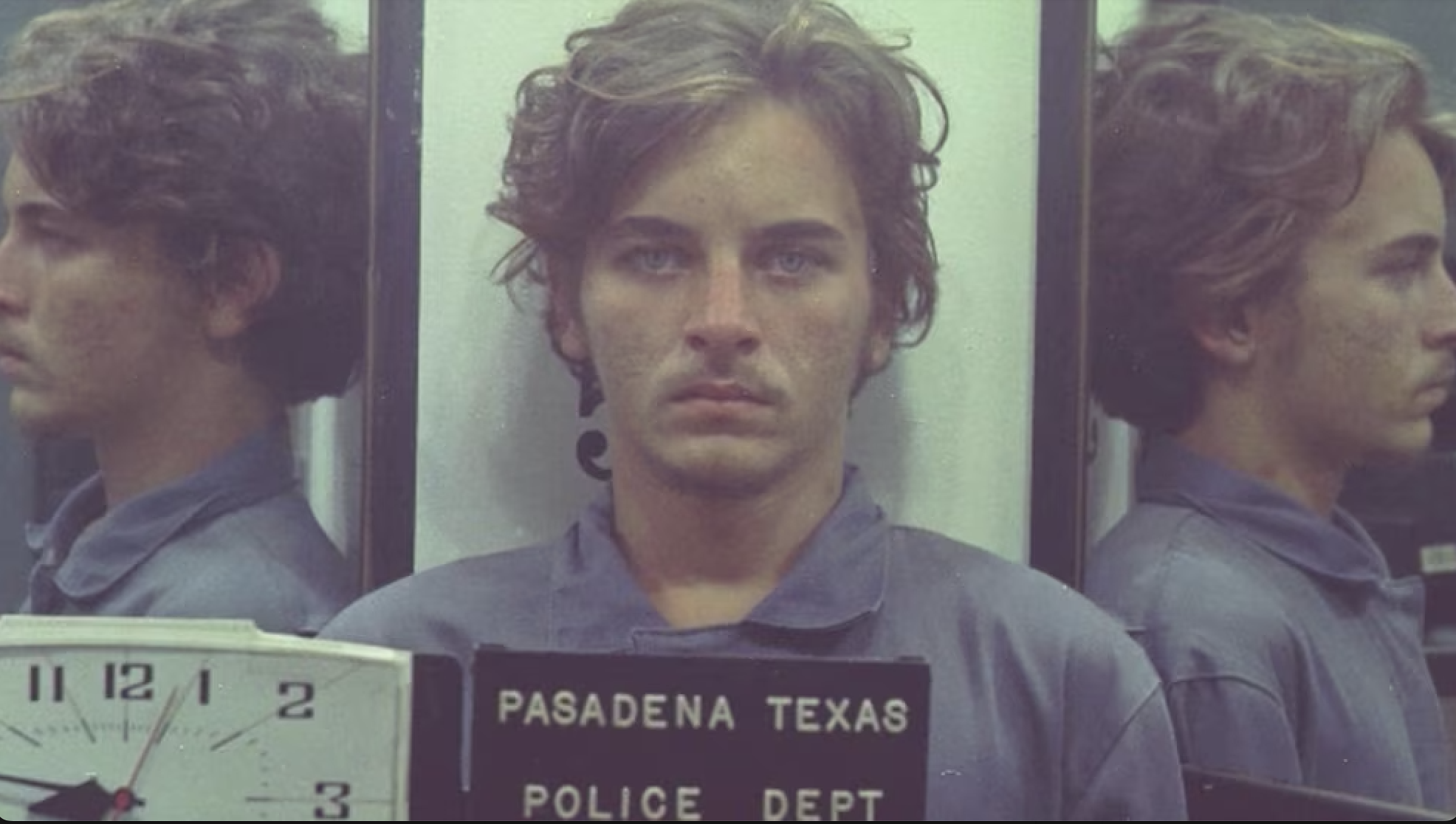

ROBERT SPRINGSTEEN: I stuck my d--- in her p---- and I raped her.

Springsteen told them he shot one girl and raped her.

Joe James Sawyer: He was so tired of this. He'd already been questioned. He'd already been through that mill. He thought, you know what? I'll tell you any damn thing you want.

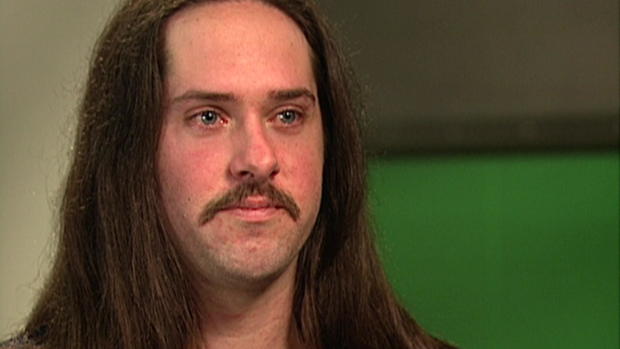

Sawyer maintains his client is innocent and says the confession was coerced. In 2009, Robert Springsteen explained to "48 Hours" why he would admit to doing something so horrible—something he says he didn't do.

Robert Springsteen: I was berated and berated and berated by the police officers. Until they obtained what it was they wanted to hear, they were not going to allow me to leave. And I basically— they broke me down.

Erin Moriarty: Let me just ask you, did you have anything to do—

Robert Springsteen: No. I did not.

Erin Moriarty: — with the murders at the yogurt shop?

Robert Springsteen: No. Never.

Even though Joe James Sawyer didn't have Michael Scott as his client, he says he has serious concerns about his confession, too.

OFFICER (INTERROGATION): Is that the gun you shot somebody with, Mike? Is that the gun you walked up behind somebody with and shot in the head?

Joe James Sawyer: I frankly couldn't believe it. … They terrorized him. And he was afraid to say no.

Forrest Welborn denied having anything to do with the murders, but police were convinced he was the lookout that night and Michael Scott placed him at the scene. Erin Moriarty spoke to Welborn in 1999 in jail shortly after his arrest.

Erin Moriarty: Were you there that night?

Forrest Welborn: No.

Erin Moriarty: Were you there as a lookout?

Forrest Welborn: No. I'm innocent.

Erin Moriarty: You had nothing to do with this?

Forrest Welborn: Nothing at all.

Welborn had been questioned multiple times by investigators over the years, and he never wavered. He, like the others, first came on police radar when, in 1991, just days after the murders, Maurice Pierce had been caught with that .22 caliber gun at the mall near the yogurt shop. Pierce told the detectives back then that he had given the handgun to Welborn and that it had been used in the yogurt shop murders.

Erin Moriarty: Why would he say that?

Forrest Welborn: I don't know.

Welborn has always maintained his innocence despite pressure from the police.

Forrest Welborn: They would get right in my face and, you know, tell me everything I said was a lie.

Remember, false confessions in this case were nothing new. Jones said that six written false confessions were obtained when he was in charge. So, when he learned that the two confessions were all the new investigators seemed to have, it gave him pause.

John Jones: I go, well, maybe I shouldn't get that shirt out just yet.

It wasn't long before the case against the men began crumbling. Charges against Forrest Welborn were dismissed after two grand juries failed to indict him. And later on, charges were dropped against Maurice Pierce for lack of evidence. Everything fell apart except the cases against Michael Scott and Robert Springsteen. And with Scott and Springsteen's confessions, the victims' families felt prosecutors had a strong case.

Barbara Ayres-Wilson (outside courthouse, 2010): These young men have been implicated and they have confessed. And they can withdraw it, but the truth is, they actually were there, and they actually did the murders.

A DNA BREAKTHROUGH?

In 2001, nearly 10 years after the murders of Eliza Thomas, Amy Ayers and Sarah and Jennifer Harbison, the yogurt shop murder trials began. Both defendants — Robert Springsteen and Michael Scott — faced the death penalty.

Joe James Sawyer: The only thing that ever tied Robert or Mike Scott to that crime scene were their confessions.

Confessions that both defendants said were coerced. The two were tried separately. Springsteen's trial was first. Neither of the men would testify against one another. So instead, prosecutors used their confessions against one another, reading parts of the confessions to the juries. Springsteen's lawyer, Joe James Sawyer, was frustrated that he couldn't cross-examine Scott.

Joe James Sawyer: I thought the trial was massively unfair to my client and that it was being done systematically and with deliberation.

The trial lasted three weeks. The jury deliberated for 13 hours and then, reached a verdict.

JURY FOREPERSON: We the jury find the defendant Robert Springsteen IV guilty of the offense of capital murder …

Guilty. Springsteen was condemned to death row.

In 2002, Michael Scott went on trial. He was convicted as well. He was sentenced to life in prison. But the case didn't end there. Fifteen years after the murders, came a shocking turn of events.

NEWS REPORT: In a 5-4 decision, the court behind me said that Michael Scott's constitutional rights were violated during his trial and therefore should get a new one.

Both Scott and Springsteen's convictions were overturned on constitutional grounds. The Sixth Amendment gives defendants the right to confront accusers — and remember, in Scott and Springsteen's trials, their confessions were used against one another, but they weren't allowed to question each other in court.

Joe James Sawyer: And the relief … the relief was incredible.

But that relief for the defendants came as a devastating blow to the victims' families. We later spoke to Eliza Thomas' mother, Maria, about that moment.

Maria Thomas: Every time I hear those words, "that their rights were violated," I just feel like I'm going to go insane. … Their rights are violated. Our girls were murdered.

Sonora Thomas: It ruins your sense of fairness. It ruins your sense of — that we live in a just world.

Even though their convictions were overturned, Scott and Springsteen were not released. A new district attorney, Rosemary Lehmberg, was determined to retry them. In an effort to find more evidence, her office had ordered DNA tests on vaginal swabs taken from the victims at the time of the murders. It's called Y-STR testing — and was fairly new in 2009 when "48 Hours" spoke with D.A. Lehmberg.

Rosemary Lehmberg: This technology searches for male DNA only

A partial male DNA profile was obtained from one of the victims believed to have been sexually assaulted. And no one expected what it would reveal.

Erin Moriarty: Does that DNA match any of the four young men who were originally accused and two of them who've been convicted?

Rosemary Lehmberg: It does not.

The DNA did not match any of the original four suspects, including Scott and Springsteen. And that's significant because Springsteen, in that confession he said was coerced, told investigators he raped one the girls.

CeCe Moore is a DNA expert and genetic genealogist whom we asked about the case and the role of Y-STR DNA in criminal cases.

CeCe Moore: It is a tool that can eliminate almost everyone … It should eliminate everybody but the suspect.

Erin Moriarty: If their Y-STR does not match, they did not contribute that DNA?

CeCe Moore: Because of … where that DNA was found, yes, in this case, it's very important.

The district attorney was focused on finding the source of that DNA — she wondered if Springsteen and Scott had another partner.

Rosemary Lehmberg: I remain really confident that … both Springsteen and Scott were responsible for killing those four girls.

But in 2009, with no matches on that DNA, Lehmberg dropped charges against Springsteen and Scott. After nearly 10 years behind bars, they were released — but not exonerated, leaving open the possibility they could be retried at a later time.

ROSEMARY LEHMBERG (at press conference): This was a difficult decision and one I'd rather not have to make.

The question remained though: whose DNA was it?

Amber Farrelly: I know who it is.

Joe James Sawyer: The killer's.

Erin Moriarty: You're convinced that that —

Amber Farrelly: That is a certain truth.

Amber Farrelly was part of both Scott and Springsteen's defense teams. She came up with a theory that the mystery DNA might belong instead to two never-identified men who witnesses reported seeing sitting in the yogurt shop just before it closed.

Amber Farrelly: Those two men were described wearing fatigued-colored jackets. …They were very slouched over, whispering, like they were — it was a very close conversation in a booth.

Officials tried to track down those two men as well as the source of the DNA. And then, in 2017, an Austin police investigator searched a public online DNA database to see if he could get a hit. And, unbelievably, he did.

Michael McCaul: I thought, my God, we actually have a chance, a shot to solve this crime after so many years.

WHO KILLED THESE GIRLS?

Congressman Michael McCaul: I really thought this was it - I really thought we had a chance to solve it.

United States Congressman Michael McCaul, like so many others from Austin, hoped that the recently uncovered DNA in the Yogurt Shop murder case might finally bring answers to the victims' families.

Congressman Michael McCaul: We'll never forget that tragic day. It's stained in my memory.

Twenty-five years after the murders, the Austin Police Department went searching for a match to the Y-STR DNA that had been found on the yogurt shop victim believed to have been sexually assaulted. And, in 2017, they got a break. On a public DNA database used for population studies, investigators thought they had found a match.

Congressman Michael McCaul: I've seen DNA … prove homicide cases. … the DNA evidence is really the key here.

But that sample from the crime scene was not a complete DNA profile, it was just Y-STR — the male portion of DNA. And, it was not a very detailed sample, having just 16 markers.

CeCe Moore: Sixteen STR's is not a very powerful match … there could be millions of people with that same profile … So, in genetic genealogy … We usually use 67 or 111 markers, or maybe even more.

Erin Moriarty: But isn't it a place to start?

CeCe Moore: It is … It's not absolute, but if there's nothing else to work with, it is certainly something to look into.

Still, it seemed to be the most promising lead in years. But there was a problem: the seemingly matching sample on the public database had been submitted anonymously by the FBI. It belonged to a federally convicted offender, arrestee, or detainee, but had no name attached to it. When Austin authorities tried to get a name, the FBI would not provide it, citing privacy laws.

Congressman Michael McCaul: There are some restrictions on privacy … And so, it gets into some very sort of, dicey issues.

Frustrated, officials reached out to Congressman McCaul for help.

Congressman Michael McCaul: And so, I pressed the FBI very hard.

Finally, in early 2020, the FBI agreed to work with the Austin Police Department to see if further testing could be done on that Y-STR DNA from the crime scene.

Congressman Michael McCaul: I was very excited about it. The idea that we could bring this case to closure for the families and bring those responsible to justice.

More advanced testing came up with additional markers: 25 instead of the original 16. But as so often happened in this case, what seemed so promising, turned into disappointment.

Some of the additional markers did not match the FBI sample. In other words, what seemed to be a match, was not. In a letter to Congressman McCaul, the FBI explained the new results "conclusively exclude the male donor of the FBI's sample … as such, the FBI Y-STR profile is not an investigative lead."

Congressman Michael McCaul: And that was the greatest disappointment because we really thought we had it.

Erin Moriarty: If it didn't match that individual, doesn't it still mean there's somebody out there — this DNA belongs to somebody, right?

Congressman Michael McCaul: It does. It does. And that's why we're not going to rest till we find the match.

Erin Moriarty: How important then, is this DNA profile that exists … to solving this case?

Congressman Michael McCaul: I mean, it's everything.

With DNA research advancing so quickly, there is real hope that one day, that sample of DNA obtained 31 years ago, may finally solve this case. Still, it will not erase the pain or loss of lives.

Sonora Thomas: Every year that goes by, I get farther and farther away from my sister, yeah. And I worry about losing memories.

Sonora Thomas struggled for years with panic attacks and physical pain, until, with the help of therapy, she realized it was connected to the murder of her sister Eliza. With a unique understanding of what trauma victims experience, Sonora wanted to help others like her, and became a therapist.

Sonora Thomas: There's so many moments, you know, when your heart is open, you know, you're joyful. But there's also this loss that's always accompanying your life.

Sonora found it helpful to look for ways to remember Eliza.

Sonora Thomas: When we got married, we had a flower and an empty chair at our ceremony, and my sister was mentioned.

Compounding Sonora's pain, her mother died in 2015. Maria Thomas passed away with so many unresolved questions about the murder of her daughter.

Sonora Thomas: There is a kind of torture that continues by the fact that it's unsolved and it's ongoing.

John Jones (shaking his head): It's always there.

John Jones is still haunted by the fact that the case is unsolved, and by what he saw that gruesome night. He has suffered from PTSD through the years.

John Jones: I had completely shut down to where all my energy was directed at the case.

Erin Moriarty: It took a toll on you, didn't it John, even 30 years afterwards?

John Jones: Well, yeah. It would on anybody, I think — not as much as the families, you understand.

Erin Moriarty: I know.

John Jones: Whatever pain I'm having pales in comparison to what they're going through.

These days, Jones finds solace singing in his church choir.

John Jones: I can relax when I'm in church.

Erin Moriarty: Leave the world behind? Leave outside?

John Jones: No, I know it's just past the door.

And when he's in that outside world, the families of Amy Ayers, Jennifer and Sarah Harbison and Eliza Thomas, are never far from his thoughts.

John Jones: I feel bad for them. That it's still not solved.

But Jones has hope. He has kept that shirt he wore the night of the murders — the shirt he promised to never wear until the case was solved. More than 30 years later, it's still sitting in there.

And sometime soon, John Jones looks forward to wearing it again.

John Jones: I just hope one of these days we can put this thing to bed, for the families' sake.

If you have information about the Yogurt Shop Murders, call 512-472-TIPS.

The Homicide Victims' Families' Rights Act was signed in to law on Aug. 3, 2022. Motivated by the yogurt shop murders, the law provides family members of cold case murder victims a way to officially request federal investigators review their case with the latest available technology.

Produced by Ruth Chenetz, Stephanie Slifer and Anthony Venditti. Michael McHugh is the producer-editor. Marlon Disla and Michelle Harris are the editors. Patti Aronofsky is the senior producer. Nancy Kramer is the executive story editor. Judy Tygard is the executive producer.