The war on opioids moves to the courtroom

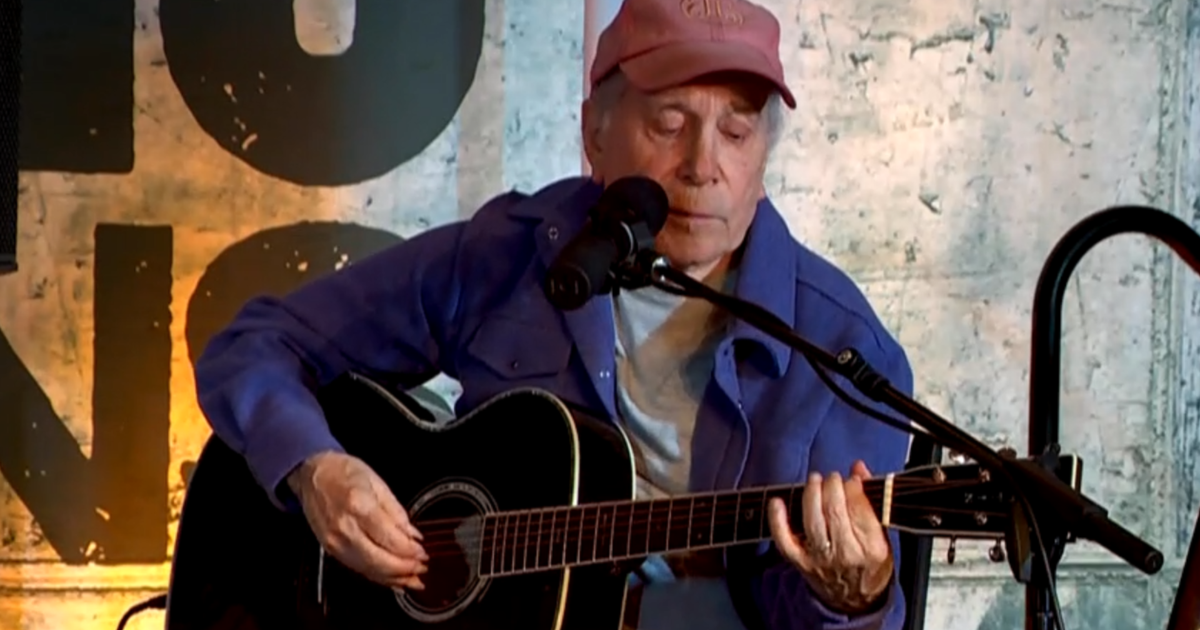

WHO'S TO BLAME for this nation's opioid crisis? If anyone is qualified to point an accusing finger, it may be the man who led the fight against another scourge years ago. Our Cover Story is reported by Lee Cowan:

"We will bring this industry to their knees right here in Mississippi, and I'm proud of that," said Mike Moore.

When Moore -- a self-described country lawyer -- first stood up against "Big Tobacco," everyone thought he was crazy.

"Let me tell you something: When I filed the case in 1994, my mom thought I was crazy!" he told Cowan. "She called me and said, 'It might be time for you to come home now.'"

They weren't laughing for long, though. Just four years later, as Mississippi's Attorney General, he negotiated the largest civil litigation settlement in U.S. history, forcing Big Tobacco to shell out more than $200 billion to help states recoup the costs of treating smoking-related illnesses.

But Moore also wanted something else: to make sure the tobacco companies pay to educate people about the dangers of their products. He made sure that nearly $2 billion of the tobacco settlement was set aside to fund The Truth Initiative, a public health campaign widely credited with reducing the teen smoking rate with sometimes shocking ad campaigns, like one in which body bags are deposited on the front steps of Phillip Morris' corporate office.

Now, some 20 years later, Moore has another health crisis on his mind -- and another corporate target: the makers of opioids.

"Tobacco, somebody smokes a cigarette, it might be 30 years, 40 years before the disease process works and kills them," Moore said. "You take too many opioids, they'll kill you today."

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, opioids killed more than 42,000 people in 2016.

The White House Council of Economic Advisers estimates that just in 2015, the cost associated with the opioid crisis topped $500 billion.

So Moore, now in private practice, is now taking his skills on the road again -- encouraging cities, counties, even entire states to come together and sue the drug makers the same way states coalesced to sue Big Tobacco.

"Tobacco [companies] told us that nicotine was not an addictive drug. They told us that smoking did not cause cancer," he said. "These companies told us that there was a less than 1% chance of getting addicted to these opioids, and that they're absolutely proven to be effective for chronic pain. Both of those turn out to be really big lies."

The nation's drug makers vigorously deny these allegations, but agree there is an opiate addiction problem. However, they suggest blaming them for the entire crisis is, in the words of one drug maker, a "stunning oversimplification."

They dismiss any comparison to tobacco, pointing out all their opiate products are approved by the FDA, and say many of those who are dying of overdoses are abusing street opioids, not legal prescriptions.

"There's plenty of fault," Moore said. "The federal government is at fault. For God's sake, the FDA should never have approved some of these drugs. The states are at fault. The companies are at fault, individuals are at fault, doctors are at fault. There's plenty of fault. We can point our fingers all day long."

"But with all those places to point the finger, why just go after the drug companies?" Cowan asked.

"Well, you can't sue the federal government, you can't sue all the individuals for taking the drugs. Trying to sue all the doctors in the country wouldn't work very well, so what I say is if there's 100% fault out there amongst many, many players, at least go to the people who made the billions of dollars on this."

So what started as a trickle has turned into a flood of litigation. There are now hundreds of city and county lawsuits being filed, as well as cases brought by at least 15 states so far -- including one of the biggest, Ohio, one of Moore's clients.

"We knew when we filed the lawsuit we weren't going to get them to the table to negotiate until we had some sort of critical mass with other states filing lawsuits," said Ohio's Attorney General Mike DeWine, who's also running for governor.

"We think if we get enough states in there, the drug companies will have no choice but to come to the table and start talking with us."

Cowan asked, "So you're not looking at this as much as punishing the drug companies, as you are holding them accountable?"

"We believe that 80% of the people who are addicts today, 80% of the people we've lost in Ohio, started with pain meds."

"You think it's their fault? No one else's?"

"Look, I think a great deal of the fault lies at the feet of the drug companies. You have to go back to these drug companies because they're the ones who misled the physicians. We firmly believe that we're gonna win. And we believe that the amount of money that the jury will come back [with] is going to be very, very high."

When asked if taking drug companies to court will do anything to help the problem, University of Kentucky law professor Richard Ausness said, "Probably not." He is concerned that money may be the driving motive behind all this litigation.

Trial attorneys, he says, stand to make millions off pooling their resources and forcing the drug companies to settle -- which also makes him wary of the precedent that these kinds of cases may set.

"Other lawsuits of this nature might be brought against other manufacturers," Ausness said. "I saw something recently about, 'We ought to sue Big Sugar -- you know, sugar does all sorts of bad things for people.' So, I don't see any end in sight. I mean, if it works for the plaintiffs, if they get something out of it, and of course the trial lawyers are doing pretty well, too, why stop?"

It may come down to a public relations battle. Drug makers don't want to be tied to images of overflowing morgues.

But that's just what's been happening in Dayton, Ohio, where the county coroner Kent Harshbarger had to build another freezer just to accommodate all the bodies of opiate overdose victims being sent his way.

"Nobody has seen anything like this," Harshbarger said. "The opioid crisis is a whole new death investigation problem."

What's different, he says, beyond the size of the epidemic is its victims. Many are from upper middle class families with no history of drug abuse … people like 27-year-old Sean Herman, who got hooked on OxyContin in college.

His mom, Sharon Parsons, didn't know it at the time, but as the pills became harder and harder to get, Sean turned to street opioids, like heroin.

"I don't think the majority of people who've become addicted, say to heroin, go out and say, 'You know what? Today I'm gonna try heroin. Let's see what that's like,'" Parsons told Cowan. "The majority start with pills."

He ended up overdosing on fentanyl, the same drug that killed Prince and Tom Petty.

"I would say from the time he first became addicted until the time he died was about five years," Parson said.

Street fentanyl is up to 100 times more potent than morphine, an illicit opiate that law enforcement can't get off the streets fast enough, says Montgomery County Sheriff Phil Plummer.

Last year in Montgomery County there were 3,637 overdoses, he said: "It almost doubled from the year before."

One of his deputies, Walter Bender, has seen all manner of addicts on patrol. But he's never seen an epidemic on this scale. He knows many of the addicts, and he tries when he can to get them into treatment. But he can't keep them there.

"We took one guy three different times to treatment," Deputy Bender said. "And each time he walked out, and we told him, 'We don't want to find you out here dead.' And the next time we had contact with him, he was found dead in the woods."

Like Sharon Parsons, Paul and Ellen Shoonover lost their 21-year-old son Matt to an opioid overdose six years ago.

"Never forget: It could be your child," said Paul. "Don't think that it's not going to happen to you because the three of us sitting here never expected it to happen to us, and it did. And the consequences were deadly.

"He was a big person in life, but maybe even bigger after he lost his life. He may have greater influence on those who need his help than he could ever had."

They've since established the Matthew B. Shoonover Educational Center, where the message is clear: Even if all the opiate pills disappeared, the millions who are addicted today will still need help for decades.

Mike Moore believes the lawsuits against Big Tobacco all those years ago led to fewer people dying of smoking-related diseases. If he can have the same effect with opioids, he says he'll be satisfied.

Cowan asked Moore, "Does it feel a little bit like deja vu for you?"

"It does," he replied. "You can't stop. You have to do something about the problem, especially if you have the talent and the connections and you're involved in this process. Why would you stop?"

For more info: