The Ungers: Righting a miscarriage of justice

The people who call themselves THE UNGERS are convicted criminals -- some 250 in all -- sentenced to life in prison many years ago for violent crimes. Thanks to an appeals court in Maryland, they now have the opportunity to be released, an opportunity many have already taken. Our Cover Story is reported by "Sunday Morning" Senior Contributor Ted Koppel:

The group has been away a long time. They are, all of them, convicted criminals who went to prison in their youth; back when Nixon, Ford and Reagan were in the White House.

In their day, Apple was just a fruit: "I don't even know how to work all this one here," said one man pondering an iPhone.

At this recent celebration in Baltimore, there's a mix here of public defenders, law school interns, social workers, murderers and rapists. The first of those convicts was released four years ago.

Charles Chappell did 39 years on a charge of murder one. He told a Baltimore County prosecutor, "I'm not going to let myself down and I'm most definitely not going to let you down."

"Good to see you again."

"Yes, sir, it's good to see you."

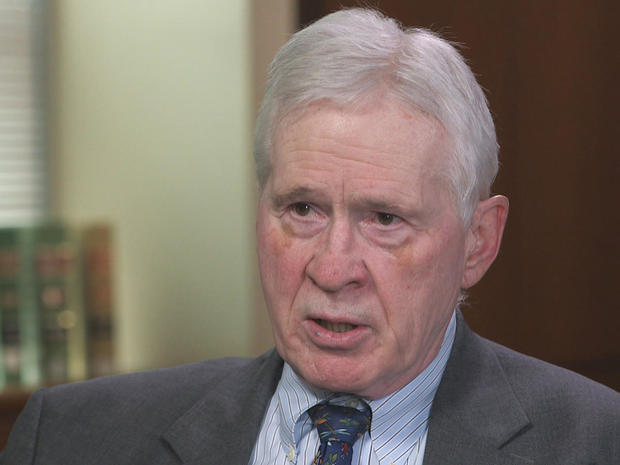

"There are a quarter-million older prisoners locked up across this country; 170 of you are now out. More to come, I hope," said Mike Millemann, a law school professor at the University of Maryland. He's also a defense attorney who was deeply troubled by the fact that for decades in Maryland, judges had been telling juries that it was their job to interpret the law pretty much as they saw fit.

It sounds incredible, but a jury could -- if it so decided -- ignore a defendant's presumption of innocence, in effect tossing the constitutional right to a fair trial out the window.

"If the jurors liked the fundamental requirement that the state has to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, they could apply it. If they didn't, they could reject it," said Millemann.

"So, the constitution was nothing more than a guiding principle?" asked Koppel.

"It was 'advice.' That really nullified the rule of law. So these, in effect, were lawless trials."

In 2012 a Maryland appeals court agreed, and ordered a new trial for Merle Unger, who was serving a life sentence for killing a police officer. That opened the door for 250 other lifers convicted in Maryland before 1981.

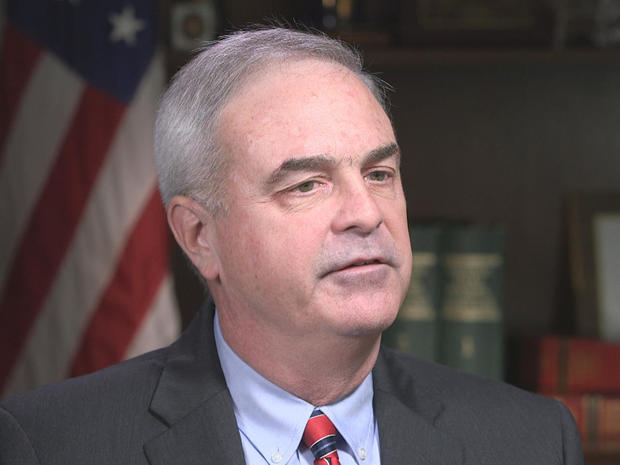

With much of the work being led by lawyers from the public defenders office, they and Mike Millemann argued that all those trials had been unconstitutional. And, interestingly, prosecutor Scott Shellenberger -- Maryland's state attorney for Baltimore County -- is on the same page:

"By saying to the jurors that they are judges of the law, it undermined those very fundamental constitutional rights of reasonable doubt and presumption of innocence," Shellenberger said.

"After they were found guilty, but in a flawed proceeding," said Koppel. "Therefore, is it in fact fair to conclude that they are guilty?"

"Well, they were granted a new trial. Now, most of those have pled guilty because prosecutors are recommending time served -- which means they get out.

With the exception, it should be noted, of Merle Unger himself. He was retried, reconvicted, and is still in prison. In acknowledgement of his case, the now more than 180 prisoners who have been released refer to themselves as "the Ungers."

Over four years, there have been a few misdemeanors, but so far, not a one of the Ungers has committed another felony.

Millemann said, "The success of the Unger folks should be a beacon for the whole United States of America."

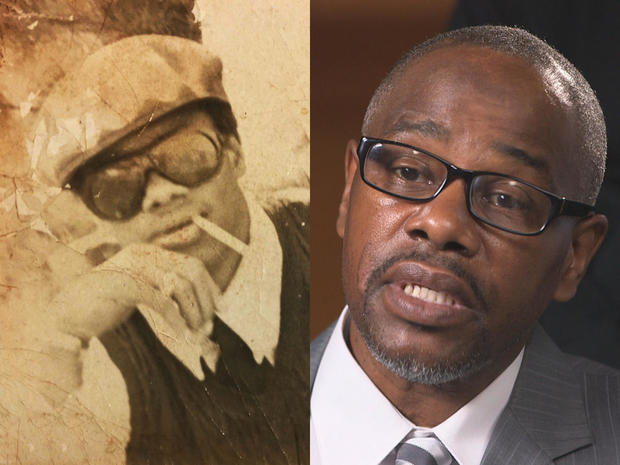

Kareem Hasan was one of the first of the Unger group to be released. According to his count, he spent 37 years, nine days in prison.

"So if I said to you, 'You're out on a technicality,' how would you feel about that?" asked Koppel.

"Well, I was just trying to get out. I didn't care how I got out," Hasan laughed. "You know, after 37 years I said, 'Okay, why are you still sitting here? Yes, I want that deal!' Because I wanted to get out."

Etta Myers is the only woman in the group. To this day, she maintains her innocence.

"I was in prison 36 years, nine months, five hours, 24 minutes. And I didn't count the seconds," she said.

Karriem Saleem El-Amin has been out for four years now: "I served 42 years, three months and three days," he said.

"The fact that you can all remember down to the day and in some cases down to the hour how long you were in, what does that say about doing time in prison?" Koppel asked.

"That you're conscious of every day that you're in there," El-Amin said. "You don't actually count it while you're doing it. But seems like when you get closer and closer to a year, then it means something. Other than that, you're just living, trying to survive while you're in there. You don't want to just think about how much time you're doing, because there's no end to a life sentence."

Actually, when El-Amin was convicted -- when all the Ungers were convicted -- wasn't true. They were all eligible for parole.

Millemann said, "Because when they were sentenced, the norm was that if you did what you were supposed to do in prison and you were a lifer with the possibility of parole, you were paroled after 15 or even, you know, later, 20 years. So there's an expectation, if they did what they were supposed to do, they'd be coming out. And that all changed when a liberal Democratic governor in effect ended parole for lifers in Maryland."

Because? "Because a lifer in a work release program killed his woman friend and then killed himself," said Millemann.

That was in the mid-1990s and from that time on, even model inmates like Etta Myers paid the price. She had three parole hearings.

"Obviously, you were turned down at each one," said Koppel.

"No, actually I was recommended for each one," Myers replied.

And what happened? "The governor never signed off on it."

It didn't matter what the parole board ruled; without the governor's signature, there was no release.

Maryland's parole boards were still going through the motions, but their recommendations of parole for a lifer were simply ignored.

Hassan said, "So, at that time, I was married to my wife, that I'm married to now -- Miss Annette – and I made her leave me. You know, I took her off my visiting list. Told her to go ahead, enjoy her life. That I'm never coming home. And I made her divorce me."

It would be twenty more years before Hasan's ultimate release. "She came the day I came home from court," he recalled. "And I seen her. The feelings, the emotions, and everything was still there. And asked me to marry her again. And we married."

"Well, good for you."

"And it's enjoyable!"

Incredibly, and this is according to social workers who've been counseling the Ungers, 70 percent of the freed inmates were initially taken in by a family member.

Charles Chappell moved in with his sister last December. Finding work has been something else again. In prison, Chappell was head clerk in a multi-million dollar furniture business.

"And now that you're out," said Koppel, "you've got another job running another million dollar business?"

"I can't even flip a burger for Burger King because I have a felony," Chappell said.

He's been applying for warehouse supervisor or warehouse associate. "I have these skills in running a business, so I can run a warehouse," he said.

"Now part of the problem obviously is -- and I say this as a guy who's almost old enough to be your dad -- but you're an old man in terms of the labor market. How old are you now? 60?"

"I'm 61 years old. My disappointment is being incarcerated for 39 years, that this body has been preserved. I could do ten years of labor Mr. Koppel and I know that I would hold up. So I'm asking for not the online interview. I would like a face-to-face interview, so where they could see a 61-year-old man who is ready to become a productive member of society."

Scott Shellenberger is a tough prosecutor who takes a common-sense approach. Koppel asked him, "When we talk about imprisonment, we're talking about two things. First and foremost, punishment for a crime. But secondly, implicit in that is also the notion of the possibility of rehabilitation. Your thoughts on that?"

"Well, certainly, I do believe in rehabilitation in the criminal justice system," said Shellenberger. "When we get to murder, I believe there has to be a balance, and that balance has to strike between the appropriate punishment and what's going to happen when you're released in society. The studies show that most violent crime is committed by men between the ages of 17 and 35. And the Ungers are a perfect example that you can age out of violent crime."

Wayne Brewton-Bey only got out last Spring. After decades in prison, he needs the support of the other Ungers. It may be that only another Unger can appreciate how disorienting the outside world can be -- even the old neighborhood. "My heart just fell outta my chest," he said. "I couldn't believe all the abandoned homes around here. And once the neighborhood was so beautiful."

Still lingering after all these years are the memories of what some basketball coaches were telling Brewton-Bey when he was a youngster, and what his fellow inmates called him: "The Legend."

"Still makes you smile now?" Koppel said.

"Absolutely!"

"Could'a been?"

"As a matter of fact, my mother used to always say that I was supposed to be living in a mansion. That's what she used to tell me when she used to visit me."

Just then, a young man with a basketball was spotted walking down the street. Koppel asked Brewton-Bey, "Give you any thoughts?"

"Yeah. That's how I was. Going, looking for a game at one point in my life."

Brewton-Bey's mother, who waited almost 38 years for his release, died the year before he came home. But his wife, Vickie, was waiting for him. They've renewed their vows. And his 10-year-old granddaughter, Madison, is helping Brewton-Bey adjust to the brave new world of the internet.

It needs to be said that even these tiny stories of long-deferred happiness must grate on the families of the victims.

Koppel said, "Well, I'm gonna put it to you very brutally. Tell me why you're an asset to the community."

"Because I believe I can save lives by sharing my story with a lot of the younger guys and women in the neighborhood, and that one mistake, one bad choice can ruin your life forever," Brewton-Bey replied. "I took a young man's life. And so his family suffered. My family suffered. 'Cause I went to

prison, I took my whole family with me. And during the process of my incarceration my family spent $10-20,000 on legal fees, which they didn't have. You know, they went in debt for me.

"And I believe I owe Earl Jenkins a debt."

"He's the man you killed."

"The man whose life I took."

The Ungers are guardians of a fragile success, and they are acutely aware of what their failure would mean. Their motto: "Failure is not an option."

Because? According to Charles Chappell, "There's so many guys that we left behind who may not have 'Unger.' But our success will show those individuals who are making these major decisions on individuals who have rehabilitated themselves. after 30 to 40 years of incarceration, that it's a possibility, because the Unger guys made it."