The trouble with Trump's weaker dollar talk

The political headlines coming out of Washington, D.C., are filled with “will they or won’t they” teases on tax and health insurance reform legislation. These battles are raising the odds of a possible government shutdown before April’s end amid geopolitical tensions that could easily overheat.

But one of the standout stories this month was President Donald Trump’s comments that the U.S. dollar was too strong, which upended a long tradition of politicians tending to talk up the dollar. Expressing such a nonestablishment sentiment -- something Trump is prone to do -- led Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin to subsequently clarify that the president was “absolutely not” trying to talk down the dollar.

Yet it’s pretty clear Mr. Trump was. For regular Americans, the question is: Why would he try to weaken the greenback when a country’s currency has traditionally been seen as a proxy of its economic and financial strength?

At the core, this is a classic mercantilist strategy that Mr. Trump has accused the Chinese of abusing. When a country weakens its currency, its exports become more competitively priced on the global stage (with the trade-off of higher import prices and potentially higher inflationary pressures).

From a political standpoint, this type of muscular economic nationalism is what won Trump the White House in the first place. But from a macroeconomic perspective, this may not be the best “policy lever” to pull.

Lindsey Group’s Peter Boockvar noted that exports make up only 12 percent of U.S. GDP, while imports, which would become more expensive should the dollar weaken, total 15 percent of GDP. Higher prices would pinch consumers (who are responsible for roughly two-thirds of the economy) and squeeze profit margins of retailers (the single largest source of jobs in the economy).

Boockvar points to Japan, where aggressive currency devaluations haven’t resulted in economic deliverance, though the country has an admittedly long list of structural woes.

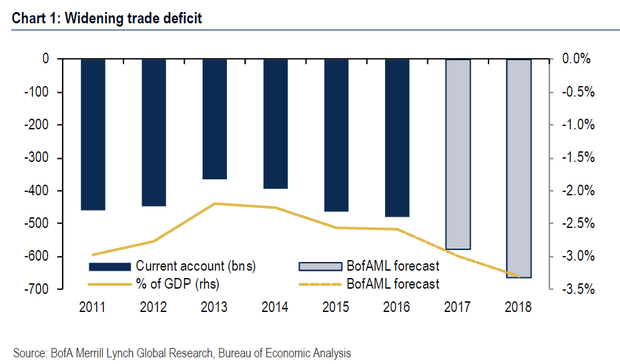

And besides, as noted by Bank of America Merrill Lynch economists, U.S. policy on the whole is likely to strengthen the dollar and help widen the trade deficit over the next few years (chart above). If that happens, it would be something of a political embarrassment for Mr. Trump.

If the president persists in his desire for a weaker currency, the Merrill economists outline two possible policy options: Outright selling of dollars in the open market via “unsterilized intervention” or reducing the inflow of foreign capital.

The trouble is, the former would risk loosening monetary policy at a time when the Federal Reserve, concerned about economic overheating and inflation, is tightening. And the latter would require policies that raise private savings, reduce private investments and reduce the budget deficit -- none of which seems forthcoming.

I think it’s safe to chalk this up as loose talk from the commander-in-chief rather than the start of a serious policy initiative. Not only are the benefits of a weaker dollar far from clear, the effort needed to lower it isn’t politically palatable.