The trail blazed by Jackie Robinson

(CBS News) Baseball season is underway, and fans are looking forward to a summer filled with drama. But nothing this year can equal what played out on a field in Brooklyn more than half a century ago. Susan Spencer of "48 Hours" tells the tale . . .

When the seasons changed in April 1947, baseball and the country began to change as well.

Jackie Robinson, number 42, made his debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers -- the sole black man in an all-white league.

"My first thought was, 'Can he help us win the pennant?'" said Ralph Branca, who was a young pitcher with the Dodgers back then. "I didn't care about the color of his skin."

But Branca knew others DID care. He made an effort on Opening Day to stand by him.

"I was just thinking that, you know, somebody had to stand next to him. And it might as well be me, because other guys may have left a space, you know?"

The upcoming movie "42" focuses on Robinson's remarkable rookie season, and his courage in the face of hostility and racism, at a time when schools and the military were segregated, the Civil Rights Bill a distant dream.

At one point, several of his teammates signed a petition to ban Robinson from the game. It failed, but the jeers and taunts continued.

"They threw watermelon on the field, black cats, those little bales of cotton, and they would be on his case," said Branca. "And Ben Chapman, who was the manager of Philadelphia, I mean, he had what we call leather lungs. You could hear him all over the ball park. And he would be on Jackie's case and say -- and I can remember what he said - 'Hey boy, come over here, I need a shine.' 'Hey boy, how come you're not workin' on the Pullman, as a porter?' 'Hey boy, let me cover here, let me rub your head,' He'd say those things."

"And nobody said anything?" Spencer asked. "No," he replied.

Then a new bride, Rachel Robinson attended every one of her husband's home games, as determined as he to answer the abuse by ignoring it.

"What we worried about, for instance, pitchers would throw at his head, deliberately," she told Spencer. "I worried about him getting hurt. There were times when it was very painful. And particularly when you're being attacked and you can't respond."

The man who put Robinson in this near-impossible situation -- convinced he could handle it -- was Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey, played by Harrison Ford.

"He was willing to fly in the face of convention against all of the other leadership in organized baseball," Ford said.

"It sounds a little grandiose, but I felt like it was us against the world, you know?" Rachel Robinson said.

Rachel and Jackie Robinson were married for more than a quarter of a century, until his death in 1972.

Spencer said the film "42" also portrays "a beautiful love story."

"Yes, we loved each other so much, from the very beginning to the very end," Rachel said.

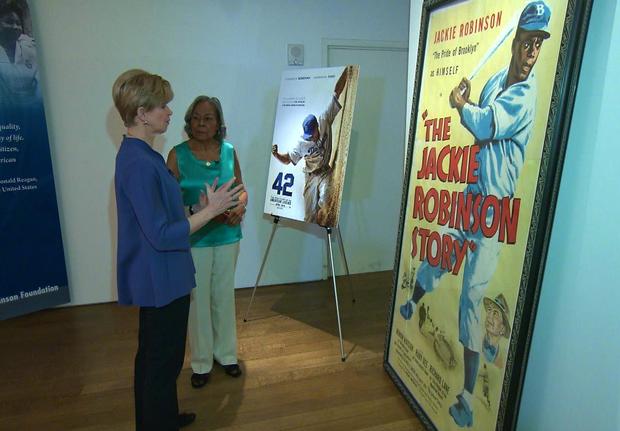

Now 90 years old, Rachel Robinson is the founder of the Jackie Robinson Foundation, which gives college scholarships to deserving students. A consultant on the movie, she helped reconstruct scenes like her first trip down South, where she encountered a "whites-only" bathroom.

"We were bumped from two planes and white passengers were put on," she recalled. "And when we were bumped in New Orleans, I was absolutely so frustrated and so angry. I saw signs -- 'White ladies only,' or 'Black,' you know, the signs that I'd never seen in California." It was, she said her first taste of "real racism . . . where it dictates what you can do and what you cannot do."

But on the field, Jackie Robinson's all-star play slowly changed the attitudes of many of his teammates.

"Pee Wee Reese is the best example," Rachel said. "He was the team captain. And he was from the South. And one day he walked over to Jack and put his arm around him, in the ball park, when fans were watching."

That was 1947. Now, more than six decades later, at Citi Field (home of the New York Mets), Jackie Robinson's number 42 literally stands tall.

And it holds a similar place of honor in all of baseball. In 1997, in an unprecedented move, it was officially retired, so no new player ever will wear 42 again.

But for one game each season, EVERY player wears it -- in honor of Jackie Robinson.

"What is it like to look out and see every player on the field wearing 42?" Spencer asked Branca. "Oh, that's great," he replied. "I mean, that shows that, you know, they understand what Jackie did."

Earlier this week, the First Lady hosted Rachel Robinson and the cast of "42" at the White House.

"It would have been easy for them to get mad or to give up," said Michelle Obama. "But instead, they met hatred with decency. I want you all to keep that in mind -- they met hatred with decency.

"Jackie Robinson certainly was a tremendous athlete, but he was so much more than that," she added.

"People sometimes have looked at what [Jackie] did, and kind of drawn a line from Jackie Robinson to Martin Luther King to Barack Obama," Spencer said. "Is that overstating the case, do you think?"

No, said Rachel. "I don't think it's overstating the case. I think that we grow and make contributions based on the shoulders we stand on. We can't say that what Jack did put Obama in office, no. But these things are connected. These lives are connected."

Robinson's accomplishments -- as a ballplayer and a humanitarian -- ultimately earned him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor.

Branca called Jackie a trailblazer who made it easier for Martin Luther King, " 'Cause he was the first, and went through the first turmoil."

When asked how she would like her husband to be remembered, Rachel Robinson said, "As a person who cared about his race, his family, and his country."

For more info:

- Jackie Robinson Foundation

- ralphbranca.com

- "42" (Official site)

- Jackie Robinson timeline (MLB.com)

- Jackie Robinson, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, N.Y.

- Ebbets Field (Ball Parks of Baseball)

- "Jackie and Me: A Very Special Friendship" by Tania Grossinger; Illustrated by Charles George Esperanza (Sky Pony Press)