The San Judas Break: Where migrants pour into America

On a stretch of dusty road in Southern California, a towering steel fence demarcates the U.S.-Mexico border, clearly intended to do more than simply note where countries begin and end. But as the road gives way to a rocky outcropping on a hillside, the steel beams stop short. An impromptu tangle of concertina wire attempts to fill the space.

Thanks to social media, TikTok in particular, this gap has now become internationally known. While at the border last month, 60 Minutes saw migrants from around the world step around the coiled wire and into the United States — and the fastest growing group among them is from China.

The San Judas Break

The illegal entryway is near Jacumba Hot Springs, CA, a town about 60 miles east of San Diego. Named for the neighboring Mexican town, the gap in the fence is known locally as the San Judas Break.

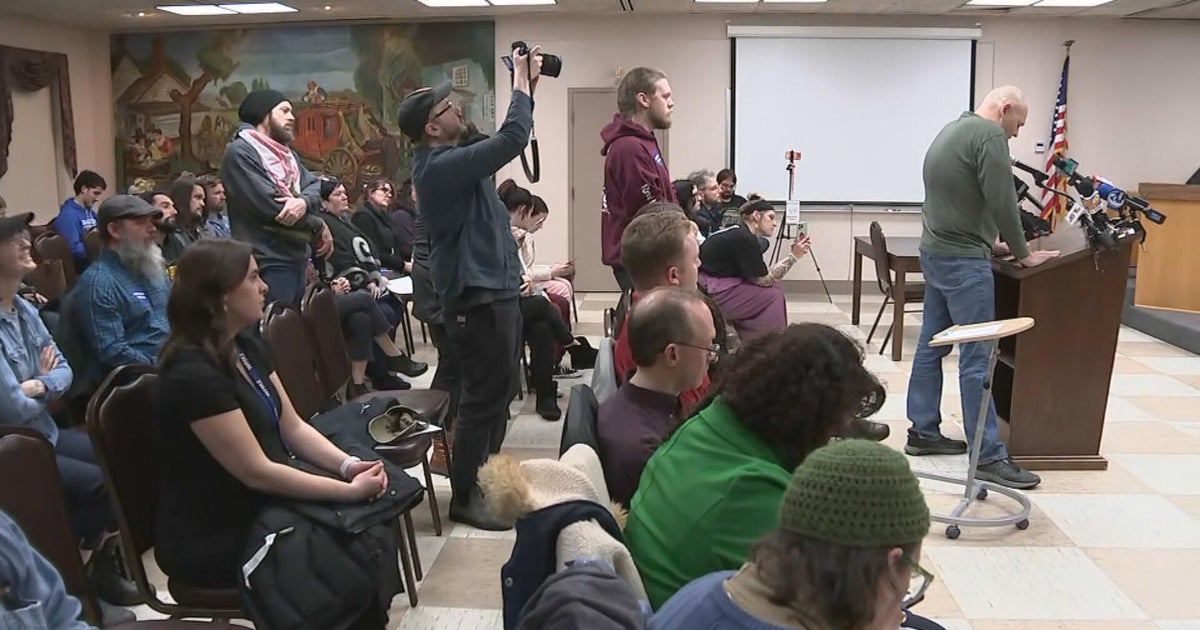

Sam Schultz, a Quaker and former aid worker, lives nearby. He told 60 Minutes correspondent Sharyn Alfonsi that he feels an obligation to help the migrants by offering food and clothing as they wait to surrender to U.S. Border Patrol.

And since the San Judas Break began attracting asylum seekers last May, there have been a lot of people to help.

"This hole is big enough that I have seen 150 people walk through it in less than a minute," Schultz said.

According to Schultz, the Chinese migrants he has spoken to have arrived at the San Judas Break in one of two ways. Some fly to Ecuador, which does not require a visa for Chinese nationals, and then take an overland route, zig zagging up through South and Central America on buses, their passports marked only with an Ecuadorian stamp.

Others, Schultz told 60 Minutes, have told him they flew directly to Mexico, first to Cancun and Mexico City, before making their way to Tijuana.

But if people in China have known about a four-foot gap in a fence nearly 7,000 miles away, why hasn't the U.S. government addressed the issue?

"I have asked this question to everyone, everyone that I ever contact in the Border Patrol who's official at all," Schultz said.

Where some migrants go

Once the migrants have surrendered to Border Patrol, they usually spend a couple of days in U.S. Customs and Border Protection custody, where each gets a background check. Some are interviewed. After that, many of the migrants are released, and buses bring them to San Diego to one of three transit centers.

San Diego County paid $6 million to set up one of the centers, where today up to 600 people come through daily. There, volunteers help migrants get to their desired destinations around the U.S.

The migrants' needs vary widely once they arrive at the center.

"Some just need to charge their phone, and they're self-sufficient. They call an Uber, and they're gone," said Kathie Lembo, the CEO of SBCS, a nonprofit organization that helps children, youth and families in San Diego County.

Others need help, including with buying airline tickets. Because some only have cash and not a credit card, SBCS takes the cash — be it, for example, Mexican pesos or Chinese yuans — and purchases the ticket on the organization's own credit card.

Some need money to make it to their next destination.

"The County of San Diego funded this center, so those are the funds that are utilized if someone needs assistance with airfare," Lembo said. "We're real judicious about doing that."

Lembo does not see her work as enabling migrants to cross the border illegally. Instead, she said, it is necessary work to help the communities in San Diego who are shouldering the influx of migrants. Her organization's work helps the migrants move onto the next phase of their journey in the United States. Only 0.5% of the migrants who have arrived since mid-October have stayed in San Diego.

Up until that point, Lembo said, Border Patrol was dropping of the migrants at San Diego trolley stations, sometimes upwards of 900 people a day.

"So you could imagine the impact on those communities," Lembo said.

Once some of these Chinese migrants leave San Diego, they frequently head to San Francisco or New York City, where they will wait for their asylum court hearings, often for years.

Back at the San Judas Break, Sam Schultz does not expect the flow of migrants to cease. He said he recently spoke to someone who had been stuck at the airport in Tijuana while waiting for a flight.

"He saw over 500 people from other nationalities flying into the airport — a lot of Chinese, a lot of Turks," Schultz recalled.

"They're not going to the beach in Ensenada."

The video above was produced by Guy Campanile, Lucy Hatcher, and Brit McCandless Farmer. It was edited by Sarah Shafer Prediger.