The real risk of rising interest rates

More than three years ago, the bond "king," PIMCO's Bill Gross, announced that the world's biggest bond fund had reduced its U.S. government-related debt holdings from 22 percent in December 2010 to just 12 percent in January 2011, at that time its lowest level in two years. Shortly thereafter, PIMCO announced it had entirely eliminated government-related debt from its flagship fund because bond yields had reached unsustainably low levels given the scale of government debt obligations and the likelihood of an interest rate correction when the Federal Reserve ended its quantitative easing program.

Over the years since then, so-called experts have persistently bombarded investors with warnings that interest rates were sure to rise. These experts advised investors to keep any bond holdings to only the very shortest term. Unfortunately, investors who heeded such warnings lost a valuable opportunity to earn term premiums over a period where the yield curve has been fairly steep. In fact, interest rates are currently lower than they have been throughout most of the period following Gross' pronouncements.

The lesson? Investors often ignore evidence indicating that there are no good interest rate forecasters. Many bond investors then compound that mistake by operating under the belief that rising rates necessarily must mean losses. While it's true that rising yields mean falling bond prices, unless yields rise more than is already expected, bondholders will not experience losses. In other words, a positively sloped yield curve - where long-term rates are higher than short-term rates -- will provide some protection against rate increases. This is important to understand because, in general, yield curves have been steep over the past few years.

Consider the following example. An investor has a one-year investment horizon. Suppose a one-year, zero-coupon bond is yielding 1 percent, and a two-year, zero-coupon bond is yielding 2 percent. The investor who purchases the two-year bond will earn a higher return over the next year compared with the investor who purchases the one-year bond, as long as the one-year interest rate does not increase by 2 percent or more.

Since there is no evidence that experts can forecast future rates any better than the market, as is reflected in current yields, investors should ignore all such forecasts. What the evidence does demonstrate is that a steep yield curve is precisely the time when investors have been best rewarded for taking term risk.

It's important to understand, however, that lower interest rates today do provide less protection against rising rates in the future. For example, a 10-year Treasury bond yielding about 2.6 percent today provides less protection against rising rates than if the current yield were, say, 5 percent.

With that in mind, my colleague, Jared Kizer, director of investment strategy at the BAM ALLIANCE, and Thomas Emmerling, an assistant professor at the Whitman School of Management at Syracuse University, considered this question: Given today's interest rates and reasonable expectations of interest rate volatility, what is the range of returns that a fixed-income investor can expect over the next year?

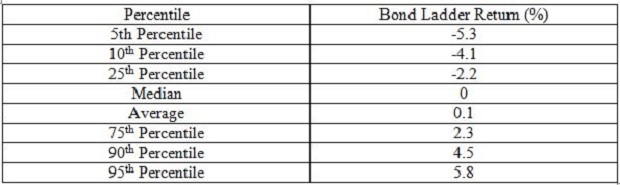

Their answer examines the forward-looking risk profile of a laddered bond portfolio with starting maturities ranging from one year to eight years. Since interest rates could change in countless ways over the next 12 months, the only way to assess portfolio risk is by simulating different changes in interest rates and calculating portfolio returns for each simulation. Using current interest rates and a model to simulate future interest rates over the next year, they examined how a portfolio of short- and intermediate-term bonds might perform. They simulated 100,000 different interest rate paths.

As the table below illustrates, they found that if interest rates were to move up sharply over the next year, the portfolio value would fall by about 5 percent. In inflation-adjusted terms, and assuming 2 percent inflation, this would result in a purchasing power decline of approximately 7 percent.

While no one enjoys negative returns, the magnitude of the bond portfolio's downside risk is significantly less than the downside risk of stocks, which can easily be 20 percent or even much greater. The main role that bonds play in a portfolio is to dampen overall risk to an acceptable level. That's a point many of the previously mentioned so-called experts seem to miss when warning investors about relatively small losses from rising rates.

It's also important to note that since most investors hold balanced portfolios of stocks and bonds, some of the scenarios in which rates increase sharply are also periods when equity market performance is strong and can offset negative returns on the fixed-income side of the equation.

The final point to consider is that while interest rate increases may lead to portfolio losses in the short term, for long-horizon investors higher real interest rates are positive for short-to-intermediate maturity bond portfolios over longer periods of time. After all, wouldn't you prefer lending your money over the next 20 years at a higher real interest rate?