The Pretender: The case of Christian Longo

Produced by Miguel Sancho, Gail Abbott Zimmerman, Chris Young Ritzen

[This story was originally broadcast on May 31, 2005. It was updated on March 28, 2015.]

Author Michael Finkel's curiosity had taken him to the far corners of the globe. But now, it was about to take him into the heart of darkness.

In 2001, Finkel was a prize-winning feature writer for the New York Times.

"...every story was extremely thrilling to me," he told "48 Hours" correspondent Maureen Maher.

He had a gorgeous home in Bozeman, Mont., and a beautiful, intelligent girlfriend who had moved all the way from Alabama to be with him.

"We felt like there was something deeper here that had to be explored," Jill Barker, Finkel's girlfriend said. "It just seemed like we should give this a chance."

But Finkel's ambition had a darker side.

"He had built his self-esteem around being Michael Finkel of The New York Times, and he was starting to get really intoxicated with all this attention," Barker said. "He was getting carried away with his career. ...It was hard to date him. Pretty soon, I realized that I had to walk away from this relationship."

His drive to outdo his competition and himself resulted in Finkel fabricating a portion of a story on child slavery in West Africa. His bosses found out and he was promptly fired.

"It was something I wish I could take back ... really badly," he told Maher.

In an instant, Finkel lost the career he'd been building his entire adult life.

Scorned by his colleagues, he retreated to Montana, awaiting the merciless media inquiries which were sure to come.

"I remember crawling underneath this space in the desk actually" he said, "as if it was a cave, an escape."

The first call came sooner than expected, but the reporter wasn't interested in Finkel's fall from grace.

Instead, he was calling about a murder of a family in Oregon.

Astonished, Finkel learned about Christian Longo, who was under arrest in Oregon for the murders of his wife and three children. "That's the first time I've ever heard that name in my life," said Finkel.

But once Finkel learned that Longo had been posing as "Michael Finkel" of The New York Times, his journalistic instincts went into overdrive. He had to find out exactly who had been playing him.

"I basically said, 'I know that you're facing a trial. And there's things you don't want to talk about. But I'm really curious about why you chose to become me,'" said Finkel.

Several weeks later, Finkel received a collect call from Longo, who agreed to meet with him in person. After that meeting, Longo began writing a series of meticulously handwritten letters.

"Each page covered top to bottom, left to right, front to back," said Finkel.

The two also scheduled weekly phone calls, calls that Finkel recorded. And so began a journey into the mind of an accused murderer, which would later become a book, "True Story" Murder, memoir, Mea Culpa."

"This was a great story," Finkel said. "Whether or not it actually saw the light of print, it was a great story."

For Finkel, and the Oregon investigators, that story centered on one baffling question: How could a seemingly devoted family man become a cold-blooded killer? The mystery began in the quiet Oregon coastal county where Longo's wife and three children were last seen alive.

Detective Trish Miller caught the call, when the first victim was found floating near the bridge. The Lincoln County sheriff released the dead boy's picture to the local news.

"I thought, 'Oh, God, that can't be. You know, that can't be Zachary,'" said Denise Thompson, who babysat Zachary Longo and his two little sisters, Sadie and Madison. She knew Christian Longo from the local Starbucks where they both worked. "You know, this can't be happening."

By the time Thompson got to the police station, the second body, a little girl, had been found, weighted down with a rock. Thompson identified them both as Zachary and Sadie Longo.

"They were so young, you know. You don't want to see a dead child," she said.

Police hunted for Longo, his wife, MaryJane, and their baby, Madison. Thompson told them she remembered a strange conversation she'd had with Longo the very day Zachary's body had been found.

"He made it a point to come up to me while I was working, and said, 'You won't be seeing the rest of the family. My wife and I are getting a divorce,'" said Thompson.

Thompson says she was surprised by the news because the Longos seemed like a very happy couple.

A surveillance tape taken just days before shows the Longos shopping like any normal family. They had just recently moved into an upscale housing complex.

Eight days into the investigation, divers dredged up two suitcases from the harbor, just outside the Longo's apartment. One suitcase contained the body of MaryJane Longo; the second suitcase contained the body of Madison Longo.

"It meant somebody killed those two human beings and stuffed them into suitcases like garbage and put them in the water," Miller said. "Either he [Longo] was dead and a victim or he was a suspect. And chances are he was a suspect."

The biggest manhunt in Oregon's Lincoln County history was under way. But Longo had a healthy head start. One month before the murders, he'd casually written down the credit card number of a Starbucks customer. Now, he was on the run.

Before police could catch up with him, Longo would leave the country, and his old identity far behind to start a new life as Michael Finkel.

MOST WANTED

Christian Longo, wanted for killing his wife and three children in December 2001, made the FBI's Ten Most Wanted List, right alongside Osama bin Laden.

It was an unlikely place for someone so apparently devoted to his family.

The Longos came from Ypsilanti, Mich., where Chris was raised in a stable, middle-class home. He and MaryJane Baker were part of the same congregation. They married when Chris was 19 and MaryJane was 25.

MaryJane's sister, Penny Dupuie, says Longo was a real-life Prince Charming. "He made other wives jealous, because Chris did all of those things that a husband is supposed to do," she explained.

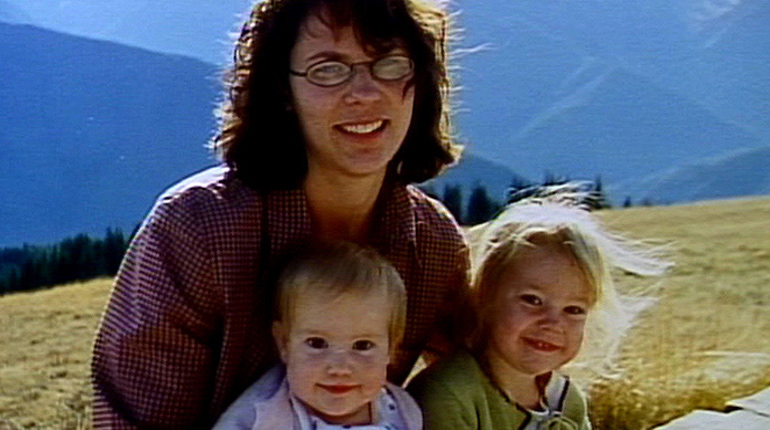

MaryJane wanted children, and she was thrilled to become a full-time mom when Zachary, Sadie and Madison came along. At 22, Longo took a job with a company that distributes The New York Times in Ypsilanti. Driven to succeed, he worked his way up to manager. Longo eventually developed a fondness for reading the Times, especially articles by feature writer Michael Finkel.

Longo would later tell Finkel that he envied the writer's worldwide adventures.

"He told me that if he was a writer, he'd like to write the same stories I wrote," Finkel said. "In other words, he was somewhat of a fan."

Longo's own life, however, was far less exotic.

At 25, he quit his job to start up "Final Touch," a cleaning company for contractors. Dupuie says the Longos had a lot of good things.

"I was wondering about the vacations that they took. They were always driving brand-new cars. Either somebody's helping, I'm thinking Chris' parents, or they are majorly in debt," she said.

Dupuie's suspicions were right. Longo was in debt, although he bragged to MaryJane and everyone else that his business was booming.

"I think honestly and truly, the most important thing to Chris was his image and money," she said.

But neither MaryJane nor anyone else knew that, to keep up appearances, Longo had turned to crime. He took a minivan for a test drive, and never brought it back. Then, he wrote himself nearly $30,000 worth of counterfeited checks from a client, and got caught.

"There was no attempt to cover up anything in this investigation," said Det. Fred Farkas, of the Michigan State Police. He had the goods on Longo. "We had seven counterfeit checks, which were each 14-year felonies."

Longo confessed, presenting himself as a financially strapped family man. "He just believed in his own mind, that he could just talk or walk his way out of the charges," Farkas explained.

In fact, Longo got off easy with probation and restitution. MaryJane believed his promise that his life of crime was over. But then, she discovered a crime of the heart, and confided it to her younger sister, Sally Clark.

"She had found an e-mail between Chris and this other woman, and he told her he had stopped loving her when she started having children and that she wasn't any fun anymore," Clark said. "And she was spending too much time and attention, you know, towards the kids instead of him."

"She didn't want her kids to grow up without their father," Clark added. "And she loved Chris so deeply that she wanted it to work out."

Longo told MaryJane he needed a fresh start, so in June 2001, just seven weeks after his fraud conviction, he packed up the family and skipped town. Their new home was a warehouse in Toledo, Ohio.

"Chris is capable of conning anyone. And someone that loves you, and wants to believe you? That was probably the easiest con," said Dupuie.

Two months later, with an arrest warrant out for Longo in Michigan for violating his probation, and new reports of stolen property at the Ohio warehouse, the Longos disappeared.

MaryJane's sisters went looking for her at the warehouse. "It was awful," Clark said. "I just knew that something was wrong. It looked like someone was trying to get out of there in a hurry."

And then, MaryJane's cell phone was cut off. "There was a feeling in the pit of my stomach that never went away," says Dupuie. "I don't know what it was, just a feeling that we had to find her."

The sisters now believed Chris had never really been the doting husband that he appeared to be. Desperate, they filed missing persons reports. Then, in early November, Clark got a card from MaryJane. It was mailed from South Dakota.

The police closed the missing persons case, but Dupuie says she still believed her sister was in danger. She was right. One month later, MaryJane and her children would turn up dead in Oregon, where their cross-country journey had ended. And Longo was now long gone.

Longo's life on the run finally brought him to Cancun, Mexico. While MaryJane's family was still reeling from the shock of the murders, Longo was partying in paradise. While police were hunting him, Longo was beginning a new life, as the globetrotting journalist he always wanted to be.

But little did Longo know that the real Michael Finkel would soon find him.

UNTANGLING A WEB OF LIES

As a fugitive in Mexico, Chris Longo did more than just tell people he was reporter Mike Finkel.

"He was so good at it that he could speak about my stories, his stories, eloquently and convincingly," said Finkel.

According to tourist Tom Taff, Longo, as Finkel, was actually on assignment.

"He was working on Mayan mysticism. So, he was going to ruins throughout the area, which there's a lot of them down in that area of Mexico," he said.

Like any professional print journalist, Longo needed a photographer. And fortunately for him, amateur photographer Janina Franke was staying at the same Cancun youth hostel. Franke says Longo was like the "nice guy from next door."

"48 Hours" brought Franke back to Mexico to retrace her journey with Longo that took her as far as the Mayan ruins south of Cancun. But soon, their professional relationship grew into something more, and took a little turn on the romantic side.

"He did a better job being Mike Finkel than I do being Mike Finkel," Finkel said, laughing.

Frolicking in the surf and sun, Longo was oblivious to the fact that the FBI, tracing the purchases on the credit card number he'd stolen back in Oregon, was about to crash on his party. A tour guide had recognized Longo's face on a wanted poster in the Cancun area.

The fugitive enjoyed his last moment of freedom smoking marijuana in a shack. "I saw cars pulling up, lights and people storming into this cabana," said Franke.

When police raided the campsite, Longo's new life came to an abrupt end. He was handcuffed and hauled off to be interrogated by the FBI. For Longo, the party was over. For everyone else who thought they knew him, the task of untangling his web of lies had only just begun.

After two-and-a-half weeks in Mexico, Longo found himself on a plane back to Oregon. He never spoke to Franke again. Instead, Longo would re-focus his charm on what would become his next bizarre relationship with the person he'd pretended to be, Michael Finkel.

The real Michael Finkel, freshly fired for his fictitious feature in The New York Times magazine, needed some way to crawl back from rock bottom.

"Mike was empty. He was a little lost," said Barker, Finkel's ex-girlfriend at the time. "Mike was not sure who he was. And Chris came along, the timing was perfect. He just came along at the right time and a real relationship developed."

Finkel adds, "He was the only friend or person in my life to whom I felt morally superior."

As the Lincoln County prosecutors decided how to handle their high-profile case, Longo decided to talk to only one journalist, the one that no one else wanted to touch.

During more than 50 conversations with Finkel, Longo promised the real story of the murders.

"He claimed to me that he had explanations for everything. And he told me, point blank, no ambiguity, I am not guilty," said Finkel.

In his handwritten letters over the next year, Longo described himself as an essentially good man, struggling to live the American dream.

"He needed to prove that he could not only make it on his own but be a blazing success," Finkel explained. "But he so wanted to be a success so quickly that it blinded him to many things."

Longo claims the check forging was not an act of greed, but a noble attempt keep his business afloat, all for the benefit of his beloved family.

"If there's one thing that Chris Longo is a master at, it's justification," said Finkel.

As circumstances overwhelmed him, Longo says he fell into a vicious cycle of lying, living beyond his means, and then leaving town. Oregon was supposed to be a new beginning. Instead, it proved to be Longo's final undoing.

"He gets a job at a Starbucks," Finkel explained. "Making $7.40 an hour part time to support a family of five. That's hard."

Once again, Longo refused to face financial reality. This time, he hustled his way into a ritzy apartment he simply could not afford.

But Longo was doing more than just spinning a tale for Finkel. He was cleverly feeding the fallen journalist's emotional needs.

"Longo not only wrote letters to me, I wrote letters to him and they were quite personal at times," said Finkel.

One of the many things Finkel revealed to Longo was that his relationship with Barker was starting up again. And Longo was giving him advice. "It was sort of like talking to a therapist," said Finkel.

Longo had become a friend. "I think one of the reasons why we didn't just talk twice and say, 'Hey good talking with you' and that is it is that we do have similar, some similarities,'" said Finkel.

Now, against his better judgment, part of Finkel was hoping that Longo would not be found guilty. "Simply put, on some level, he was such a nice guy," Finkel said. "And I know that seems so creepy and weird."

But Longo had yet to explain how his entire family had ended up dead. And with the trial now looming, Finkel began to wonder if he'd been conned like everybody else.

"If his story of his life could pass muster with me and I was grilling him on it, all these aspects of it, then it could pass muster with a jury," Finkel said. "It dawned on me that I wasn't necessarily his friend or his confidant. That I was his dress rehearsal."

LONGO ON TRIAL

One year after his arrest, Longo is about to stand trial for murdering his wife, MaryJane, and their three children.

Finkel will be at the trial, eager to hear Longo's theory of the crime. "Longo had tipped me off that there might be a surprise the very first day of the trial," he said.

It is one promise that Longo keeps. On Valentine's Day 2003, the proceedings begin with a bombshell. Longo admits killing his wife and their youngest child, Madison. But he maintains his innocence in the deaths of his older children, Zach and Sadie, confounding everyone who is following the case.

"Why would you admit to two murders and not four?" Finkel asked. "And, then of course, if he didn't kill Zachary and Sadie, then who did?"

For now, the defense leaves that a mystery. But prosecutors say the evidence is clear: Longo alone murdered all four victims, and dumped their bodies in the water.

"He didn't like being tied down to his wife and three kids, and the solution for him was to just get rid of these children and his wife and assume somebody else's identity," said Oregon District Attorney Josh Marquis, who followed the case closely.

Marquis says Longo is a sociopath who deserves the death penalty. "He made a conscious choice to commit a cosmically evil act."

At trial, truck driver Dick Hoch testifies that he met a man he believes was Longo on the Waldport bridge late one night. Hoch says he offered help, but was turned away: "He said his check engine light had came on but it was off now."

Jurors also hear about the divers' grim discoveries, and they're shown graphic images. The medical examiner says MaryJane and Madison were strangled, but he cannot determine how Zach and Sadie died.

Finkel is disgusted both with Longo, and his own bad judgment.

"You can rationalize and talk and talk and write and write and write and write," Finkel said. "But there is no way that a person can do that without having enormous amount of evil in them."

Longo takes the stand and tells the same life story he rehearsed on Finkel -- his downward spiral and his excuses for stealing and lying.

Up until the trial, when Longo told his story, he stopped just short of revealing how and why his family was murdered. But now in court, he finally continues. Longo says late one night, after feeling defeated over his desperate situation, he came home to his pricey apartment on the Oregon coast. He sat his wife down, confessed all his lies, and then he says the mild-mannered MaryJane exploded. He says, "She didn't want anything to do with me at that point."

The next night, Longo claims that he came home to find his older children missing, Madison seemingly lifeless, and MaryJane irrational: "She was literally on the floor, curled up into a ball, bouncing back and forth, hitting her back against the wall."

Then, Longo tells a stunned court that MaryJane hinted that she had killed their children, which is why, he says, he lost control: "I grabbed her with both hands, and I continued to squeeze. And I didn't stop for a long time. I didn't stop until I couldn't hold her up anymore."

Longo claims he was stuffing the bodies into suitcases when he noticed Madison was still breathing: "I put my hand on her throat and squeezed."

But in a telephone interview that "48 Hours" was able to conduct in 2005, Longo had a disturbing explanation of how he could kill his youngest child: "At that point, something else kicked in. And No. 2, I was not nearly as close with Madison as I was with my other two children."

Although no one in court heard that, Longo's testimony has taken its toll.

"I saw that he was not only lying about the murders, he was slandering his dead wife in front of her own family," Finkel said. "Just blithely speaking, complete confidence in his voice. Everything was perfectly detailed."

But Marquis believes Longo's performance had backfired.

"I think it hurt him horribly," he said. "One of the things about con men, and Christian Longo is a con man, is they can't stay off the stage. So coming up with some bizarre story which then they want to be able to say, they want to be able to convince people of becomes almost pathological."

It took the jury little more than four hours to reach its decision: Christian Longo is guilty of all four murders.

Longo says the verdict didn't surprise him: "I think I should spend the rest of my life in prison at the very least. At the very most, death."

But, he may be changing his story.

IN SEARCH OF THE TRUTH

Convicted of killing his wife and children, Chris Longo's fate now rests with jurors who will decide whether he gets life -- or death.

"Should the defendant receive a death sentence?" Judge Huckleberry addressed the court. "To this question, the jury has answered 'yes.'"

Yet, even now, Longo can't stay off the stage. "I'm starting to feel a remorse and empathy that I don't think I've felt before," he said in court.

In a shocking moment, Longo hints that he may be changing his story, and admitting to all of the murders.

"I condemn my acts from what I did in the past," Longo said in court. "And, I no longer disassociate myself from those acts. It's something that I did solely."

Then, months later, in conversations with Sally Clark, and letters to Finkel, Longo comes close to a full confession. He even gives them chilling details of how he murdered Sadie and Zachary.

"He didn't just kill them. But he brutally killed them. Those kids suffered," says MaryJane's sister, Sally.

But in speaking with "48 Hours" from death row, Longo, who is working on his appeal, reverts back to his old story.

Did he kill Sadie and Zachary?

"That's something that I'm not going to discuss right now," he said. "I'm going to essentially stick with what was brought out in court. Because that is on the record."

"Do you think we'll ever have the truth of what happened?" Maher asked Marquis.

"I think the jury, in their verdict, said what happened," he replied. "Exactly how it happened, will we ever know? No, we won't, because it's coming from the lips of a liar."

Hollywood's version of Finkel's book is about to be released. The psychological thriller focuses on the reporter and the killers' game of cat and mouse.

"I wish that parts of this story weren't true," said Finkel.

But the story of this odd friendship continues. "It's more casual than it's ever been, but he's not completely out of my life," Finkel said. "And I doubt he ever will, until the day he's put to death."

What's left to learn from Longo?

"The biggest question of all, which is why would you do this," Finkel said. "I've pretty much given up on getting an answer."

Back in Oregon, "48 Hours" brought MaryJane's sister, Penny Dupuie, to see Detective Miller, and to see a plaque memorializing the lives that were lost.

Is there something about her sister that Dupuie, would like people to know and remember about her and the kids?

"There are four people that are gone that would have made the world a better place," she said.

Prosecutors say Christian Longo's appeals are likely to last five to 10 years.

Oregon now has a moratorium on the death penalty.

Michael Finkel took Longo's advice and married his girlfriend, Jill; they have three children.