The president as communicator-in-chief

Imagine the world a century ago. There was film, of course, but the news was delivered almost exclusively in print that tens of millions had been killed in the First World War, and that tens of millions more died in a global influenza pandemic.

After the war, in France, the American president, Woodrow Wilson, mustered his wartime allies behind a so-called League of Nations. But he couldn't sell the plan here at home. Wilson crisscrossed the country by rail, delivering one speech after another.

The effort almost killed him: "It's easy to think 'OK, presidents are always kind of barnstorming, going around the country, talking to the people,'" said Jill Lepore, professor of American history at Harvard University. "But to campaign on your own behalf was considered undignified well through the 19th century. So, even just going around the country was a novelty."

In effect, Wilson was going door-to-door. But he had none of the tools that would amplify the campaigns of future presidents – not that Warren Harding recognized radio's potential. As for Calvin Coolidge? They didn't call him "Silent Cal" for nothing. Herbert Hoover? No, he never got the hang of radio, either. That was left for Franklin Roosevelt and those famous Fireside Chats.

"This bank holiday, while resulting in many cases in great inconvenience, is affording us the opportunity to supply the currency necessary to meet the situation," FDR said during his first Fireside Chat, March 12, 1933. "It is your problem, my friend, your problem no less than it is mine. Together we cannot fail."

"And he's explaining to the American people he's about to shut down the banking system," Lepore told "Sunday Morning" special correspondent Ted Koppel. "And there's an incredible intimacy to his voice, but it has a quality of compassion to it."

This, remember, was at a time when radio announcers wore tuxedos to work, when their delivery was incredibly stylized. And what did FDR do? He memorized those talks, so that his delivery was much more relaxed.

Lepore said, "He understood that radio was a performative medium, that it wasn't like other kinds of performances. FDR, I think, kind of took that philosophy to the citizenry itself, right? That he would try to enlist their support by what would appear to be a kind of casual conversation, as opposed to delivering, you know, the State of the Union address."

By the time Dwight Eisenhower decided to run for president in 1952, his Republican backers convinced Ike to try his hand at the new medium of television. "He agreed to participate in this campaign [ad] called 'Eisenhower Answers America,'" said Lepore. "And they're completely staged. He went into a studio and off of cue cards he read these answers to Americans' questions.

"And then days later, the advertising agency picked up people who were waiting in line for tickets at Radio City Music Hall, brought them in and had them read, from cue cards, the questions. And then the questions and answers are cut together."

Questioner: "General, the Democrats are telling me I never had it so good."

Eisenhower: "Can that be true when America is billions in debt, when prices have doubled, when taxes break our backs? … It's time for a change!"

Crude, but effective. He won, and would become the first president to hold a televised press conference: "Well, I see we are trying a new experiment this morning," Eisenhower said. "I hope it doesn't prove to be a disturbing influence. I have no announcements. We will go directly to questions…"

The first televised presidential debate, meanwhile, showed Richard Nixon slightly ill-at-ease with a glistening upper lip. Television viewers (and, ultimately, the voters) watched, and picked John F. Kennedy. He was the first president to master that medium.

Reporter: "There are many Americans who believe that in our manner of questioning or seeking your attention that we are subjecting you to some abuse or a lack of respect."

Kennedy: "Well, you subject me to some abuse, but not to any lack of respect!"

Ronald Reagan, with years of Hollywood experience under his belt, was, if anything, an even more polished performer.

As he stated during a presidential debated with former Vice President Walter Mondale, then 56, "I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent's youth and inexperience."

And the other presidents simply provided variations on a theme. The Carter grin that reminded folks of his humble origins as a peanut farmer; President Bill Clinton's tentative nibble of the lower lip, the slightly querulous voice; these were simply adaptive techniques to a familiar medium.

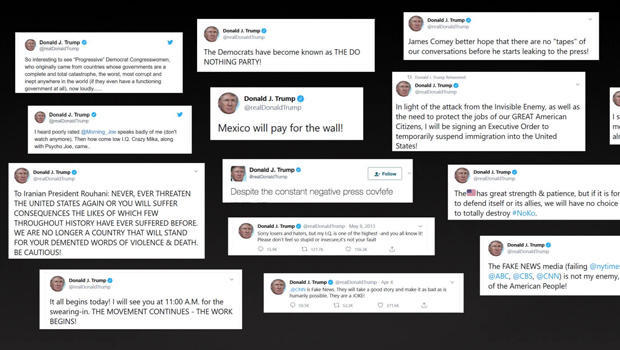

It wasn't until Donald Trump that we witnessed the end of an era, when television anchors and correspondents who once served as gatekeepers between politicians and their public were simply brushed aside.

Trump spoke to Koppel for "Sunday Morning" on the day he received the GOP nomination: "Between Facebook and Twitter, I have over twenty million people, and that's a big audience," Mr. Trump said. "And it's also, you and the media and everybody`s watching it."

"Well, it allows you to circumvent the media," Koppel said.

"It allows me to get across a point very quickly in seconds. I mean there was never anything like that. And that gives me a big, big base in terms of a campaign.

"In terms of a presidency," Mr. Trump added, "I don't think I'd use it very much at all."

Clearly, he changed his mind.

Never have presidential thumbs communicated so much to so many with such direct impact.

President Trump doesn't need the intervention of the media giants. The tweets generate so much interest and attention that the networks, cable channels and newspapers are all but powerless to dismiss them, or him.

And the dirty, little secret is that while Donald J. Trump has done everything he can to wreck the profession of journalism ("They are truly an enemy of the people, the fake news, enemy of the people! They really are! They are so bad!"), he's been very, very good for the business. More than any predecessor, President Trump sets the agenda – for what we read, what we hear, and what we watch. [As the "PBS NewHour" reported, "He posted 30 times on Twitter on Sunday alone."]

You may love him or loathe him, but just try to ignore him.

For more info:

- "These Truths: A History of the United States" by Jill Lepore (W.W. Norton), in Hardcover, Trade Paperback, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon

- Jill Lepore, professor of American history, Harvard University

Story produced by Dustin Stephens. Editor: Mike Levine.

See also:

- FDR and the recreation of America ("Sunday Morning," 5/10/20)