The populist backlash has everything to do with work

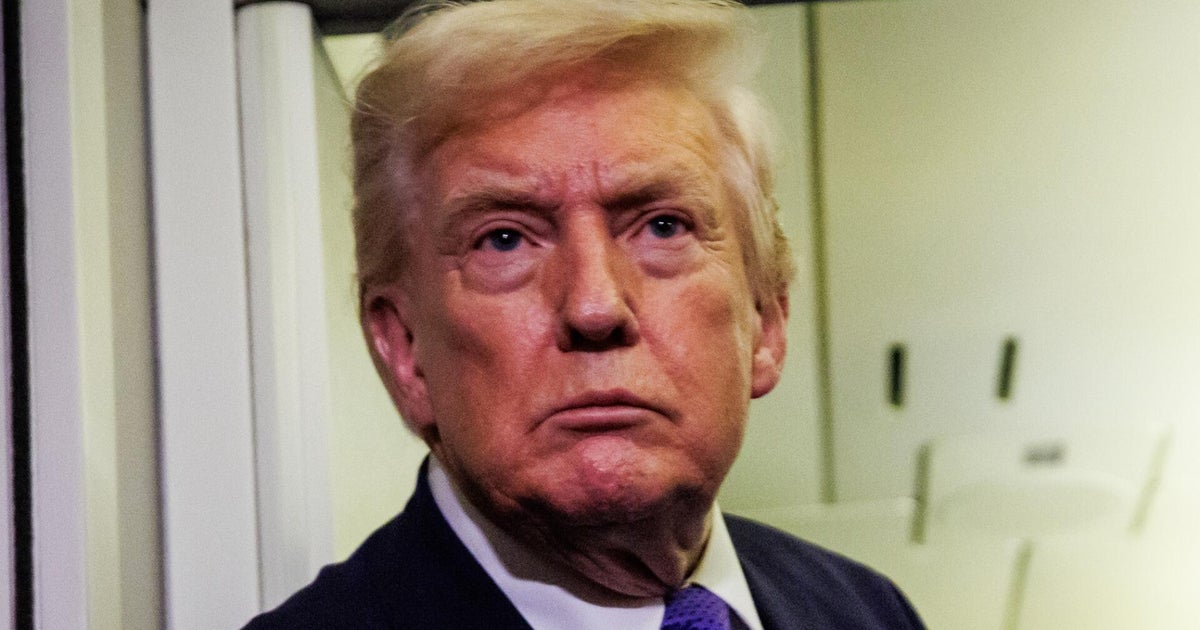

The gathering of global economy-shapers that takes place in Davos, Switzerland, every January took on a decidedly populist touch this year. U.S. President Donald Trump brought a softened "America First" message to an audience of business leaders, while India Prime Minister Narendra Modi cited backlash to globalization as one of the biggest threats to the global order. Global policymakers' fears of popular unrest were also evident in the official title of this year's meeting: "Creating a shared future in a fractured world."

For Philip Jennings, head of the UNI Global Union, there's a clear culprit behind this political situation: the economy. Specifically, the economic situation of the bottom 90 percent of the global population, who aren't benefiting from the soaring markets and whose earnings have stayed essentially flat since the Great Recession.

"One of the reasons that we have these fractures and these social tensions and dissatisfaction out there is because the working world isn't working for people," Jennings told CBS News. "We have levels of inequality that we've never seen."

Indeed, the vast bulk of the wealth created over the past year was claimed by the top 1 percent, according to a recent report from Oxfam International. The poorest 3.7 billion people on Earth received none of it.

In the U.S., where the recession officially ended in 2009, most of the jobs that have been created during the recovery have been in low-paying fields, such as restaurants, retail and certain health care sectors. Globally, he said, nearly one in two workers has a job that is temporary or otherwise tenuous. And as the technological revolution allows businesses to sustain themselves with fewer and fewer workers, the situation will only worsen, many labor advocates fear.

Jennings, whose organization represents 900 trade unions in Europe, isn't the only one sounding the alarm. The WEF meeting this year featured dozens of panels on the future of artificial intelligence, automation and what's known as universal basic income -- the idea that every citizen deserves a basic amount of money, regardless of work status.

Guy Standing, an economics professor who was among the earliest proponents of basic income, fears that "political monster" will arise if labor conditions don't improve. Some captains of industry, including some of the world's wealthiest men, have also come out in support of an income floor.

Whether that happens or not, Jennings noted one positive to the recent rise of populism in the U.S: a growing labor movement. After dropping for decades, the number of workers in unions grew by a quarter of a million last year, recent figures from the Labor Department show.

"There's a kind of reaction out there that we need to stand together and that we're stronger together," he said.