The painful history of anti-Asian hate crimes in America

As the United States struggles to open back up, Asian Americans remain anxious. Women and the elderly are taking self-defense classes; others are arming themselves for protection. Even parents are wondering if they should keep their children out of schools.

There are 23 million Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the U.S., and ever since the pandemic began, a new poll suggests one out of every three fears they will be attacked, reports correspondent Weijia Jiang.

Hate crimes overall increased last year by two percent, but hate crimes against the Asian American and Pacific Islander population rose by 146 percent, according to the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University.

For example, one man, recorded in Tustin, Calif., last December, told his victim, "Thanks for giving my country COVID."

- New data shows continued surge in anti-Asian hate crime reports in some major cities

- Nearly two-thirds of anti-Asian hate incidents reported by women, new data shows

- Anti-Asian incidents top 6,000 since start of pandemic

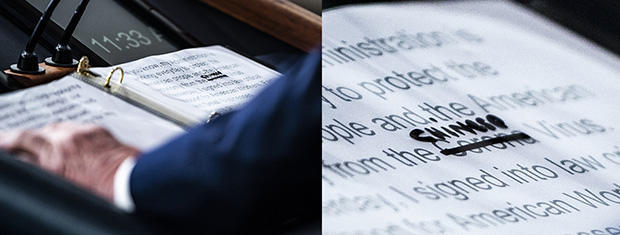

Many blame the previous administration's use of racist rhetoric for the rise in violence, as when President Trump stated, "I would like to begin by announcing some important developments in our war against the Chinese virus."

"What comes out of the mouth of the leaders, especially the president, matters," said Senator Mazie Hirono of Hawaii.

She pointed out that we're witnessing history sadly repeating itself: "[Trump] didn't create this kind of discrimination and, indeed, hatred, but I think that he called to the fore the kind of thinking that some people in our country have. We have always been deemed 'the other,' the perpetual foreigners."

"It's not just the pandemic," said associate professor Lok Siu, who teaches Asian American Studies at University of California, Berkeley. "There's an economic crisis in our country. There is a political crisis in our country. Unfortunately, because of the high visibility of Asian Americans being associated with the virus, they become the targets."

She said a battered economy has always been one of the root causes for scapegoating Asian Americans.

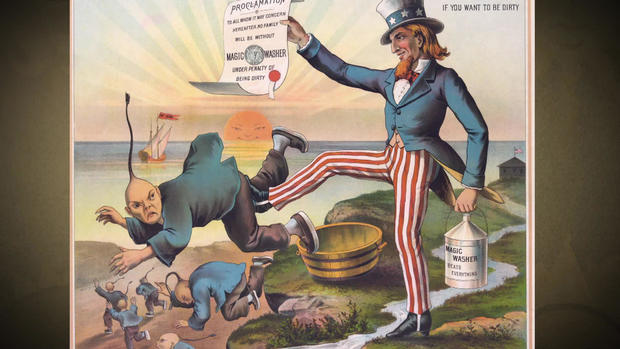

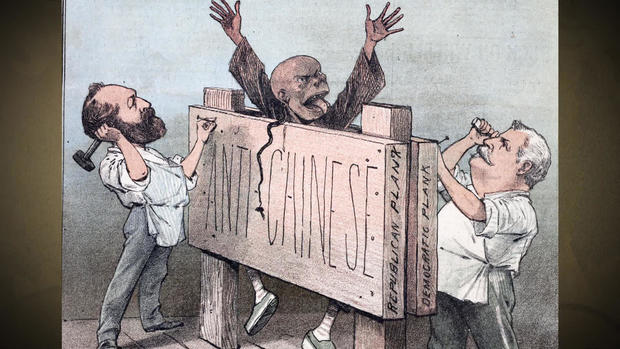

"You can see this happening as early as 1870s, with the conclusion of the railroad construction," said Siu. "You have spikes of just outraged White workers who are claiming that Chinese are taking over jobs and therefore need to be gotten rid of."

As a result, anti-Chinese rioters burned down and even wiped out Chinatowns across the nation; and in 1882, the U.S. government made anti-Asian racism official with the Chinese Exclusion Act, prohibiting all immigration by Chinese laborers. It was the first federal act of its kind barring a specific ethnic group from entering the United States – an act that was legal for 61 years, until it was repealed in 1943, right around the time that Japan became America's enemy.

In the 1965 CBS News documentary, "The Nisei: The Pride and the Shame," Walter Cronkite spoke of the wartime attitude against Japanese Americans, which would "unleash a deep racial hate against all things Japanese."

During the war, 120,000 people of Japanese heritage were forced to give up their homes, and put into internment camps. "Most are American citizens by birth. There is no proven guilt. Not even a proven military need," Cronkite said.

- George Takei: "I know what concentration camps are. I was inside two of them, in America"

- George Takei on a rueful journey back in time ("Sunday Morning")

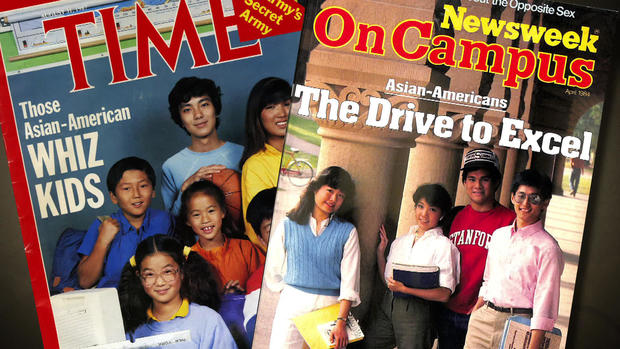

After World War II, Japanese Americans struggled to regain stability. When some eventually did, their success stories led to an enduring stereotype. "We tend to have this misconception that Asian Americans have made it, right? That we are model minorities," said Siu.

"Model minority" – two words that may sound positive together, but Siu explains the phrase is often used as a wedge.

"What it has done in the past is really pitted Asian Americans against other racial ethnic groups, on the premise that somehow, because they have so-called the 'right cultural values' – whatever they may be – that they've been able to achieve," said Siu.

The idea that Asian Americans fared better played out in the 1980s, when Michigan's auto industry was heading to the scrap heap. The scapegoat for many? Japanese imports, as in its cars and its people, sparking a new wave of anti-Asian discrimination.

Journalist and activist Helen Zia said, "If we could just imagine back in 1982, you know, a time when Japan was the enemy, everything wrong with America was being caused by Japan."

Zia was working in a Detroit auto factory the same time a 27-year-old Chinese American's name would become a rallying cry: Vincent Chin.

"He was not your 'model minority,'" said Zia. "He hadn't gone to college. He was taking night classes. He worked as a draftsman. And he worked part-time at a Chinese restaurant as a waiter. He was really your all-American, Asian American, Chinese American kid."

On June 19t, 1982, two White men, a father and his stepson – a foreman and a laid-off auto worker – beat Vincent Chin to death with a baseball bat outside a McDonald's, after an argument at the nearby bar where Chin was celebrating his bachelor party.

One of the bar workers told reporters what she heard the stepfather say to Chin: "He had made the remark about, 'Yeah, because of you, motherf****r, we're out of work!'"

Chin's death didn't make national news. The sentencing of his assailants, in April 1983, did. A charge of 2nd degree murder was reduced by plea bargain to manslaughter. The sentence: a $3,000 fine each, and three years of probation. No time in prison.

Ben Wong believed the sentence was because the victim was Chinese: "I think that is what it is. Discrimination," he told CBS News' Bernard Goldberg.

Zia said, "They were given fines of less than what a used car would've cost, that they could pay off at $120 a month. And the judge said, 'These are not the kind of men you send to jail.'"

As nationwide calls for justice grew louder, both men were indicted on federal charges for violating Chin's civil rights. They were eventually acquitted.

"Vincent was very much the American story, the American immigrant story," Zia said. "And all of that was just shattered, you know, in a climate of racism."

In 2012, the father apologized for killing Chin, but insisted it was never about race, something the Asian American and Pacific Islander community has heard again and again.

Back in March, a White gunman shot up 3 Atlanta area spas. Among the eight people killed, six were women of Asian descent. On Tuesday, the killer pleaded guilty to four of the murders, and was handed four life sentences without parole. While prosecutors in one county charged him with a hate crime, those in another one did not.

Jiang asked Hirono, "What do you say to critics who argue, 'These are not crimes motivated by hate. These are just crimes of opportunity'?"

"I say to them, they're not paying attention," she replied.

In a rare moment of bipartisanship, Congress recently passed the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act, introduced by Senator Hirono and Rep. Grace Meng. They hope it will make reporting a hate crime easier, and give federal oversight to expedite the review process. The law is largely seen as the first step. Journalist and activist Zia said the nation needs to go much further. "History shows that this is going to be more than a moment," she said.

There are renewed demands across the nation to teach Asian American and Pacific Islander history in schools, in the hopes that people will see beyond the perpetual foreigner, the model minority, or the scapegoat.

Zia said, "There really has to be a concerted, thoughtful effort to try to teach what America really is, so that we can build a country that everybody feels like we're part of it."

For more info:

- Senator Mazie Hirono (D-HI)

- Lok Siu, associate professor, University of California, Berkeley

- Journalist and activist Helen Zia

- National Japanese American Memorial Foundation, Washington, D.C.

- Eastwind Book & Arts, San Francisco

- Oakland Asian Cultural Center

Story produced by Young Kim. Editor: Carol Ross.