The opioid epidemic: Who is to blame?

The opioid crisis has been one of the most devastating public health emergencies of the 21st century. In 2018 alone, 46,802 people in the U.S. died from an opioid overdose, and health care providers across the country wrote prescriptions for opioid pain medication at a rate of 51.4 prescriptions dispensed per 100 people.

This Sunday on 60 Minutes, correspondent Bill Whitaker and producer Sam Hornblower take another look in a series of reports that asks: Who is responsible?

DRUG COMPANY EXECUTIVES AND OPIOID SALESMEN

June 2020 report

This January in a federal courthouse, there was a first in the American opioid crisis: Top drug company executives were sentenced to prison for crimes related to the public health emergency.

A jury found five executives of Insys Therapeutics guilty of racketeering and fraud, determining that they recklessly and illegally conspired to boost profits from the opioid painkiller Subsys. The judge sentenced former Insys CEO John Kapoor to a prison term of five and a half years.

In a two-part report for 60 Minutes, Bill Whitaker examined the years-long investigation that led to the convictions. Whitaker's report exposed the playbook of sales practices that helped lead to an explosion of opioid prescriptions in the last two decades.

"I was taught to forget the patient, to not think about the patient, take the human aspect out of it," former Insys senior vice president of sales Alec Burlakoff told Whitaker. "It's like selling widgets."

Before arriving at Insys, Burlakoff was a star sales representative at Cephalon, a drug company that flouted FDA regulations to sell the fast-acting synthetic opioid Actiq. Cephalon pleaded guilty in 2008 to a misdemeanor for illegal promotion, paying $425 million in fines and settlements—less than a quarter of the company's yearly revenue. Cephalon was eventually sold, and Burlakoff found a new job at Insys, where he brought along his successful opioid sales practices.

Once at Insys, Burlakoff created a program to bribe doctors as much as $125,000 a year to boost opioid prescriptions, masking the payments as a "speaker's fee."

"The key to success? The less of a conscience you had, the better," Burlakoff said.

When the Insys executives were brought to trial last year, Burlakoff cooperated with prosecutors and testified against his associates. Given his cooperation, he was sentenced to 26 months in prison.

CONGRESS AND THE PHARMACEUTICAL LOBBYISTS

October 2017 report

In October 2017, 60 Minutes teamed up with the Washington Post for a Peabody Award-winning report about how the Drug Enforcement Administration was hindered in its attempts to hold the pharmaceutical industry accountable.

Whitaker spoke with Joe Rannazzisi, a former high-ranking DEA agent who became a whistleblower. Rannazzisi said his investigators at the DEA were aware that an inordinate number of prescription narcotics were being sent to pharmacies, and they began to bring cases against the pharmaceutical industry's powerful drug distributors.

But they hit a wall — in the form their own attorneys. Rannazzisi said the drug industry used its money and influence to pressure the DEA's top lawyers into taking a softer approach.

Sometimes that pressure came from familiar faces. Former DEA attorney Jonathan Novak told Whitaker he witnessed numerous agency lawyers switch sides and take high-paying jobs lobbying their former colleagues. Suddenly, Novak said, DEA investigators could not get their cases through their legal office.

As cases nearly ground to a halt at the DEA, the drug industry began lobbying Congress for legislation that would limit the agency's enforcement powers. Congress passed a law that took away the most potent tool the DEA has — the ability to immediately freeze suspicious shipments of prescription narcotics to keep drugs off American streets.

One of the lawmakers who introduced the bill was Pennsylvania Congressman Tom Marino. At the time of the 60 Minutes report, Marino had just been nominated to be President Donald Trump's new drug czar.

Two days after the report aired, President Trump announced that Marino had withdrawn his name from consideration for the position.

THE DRUG DISTRIBUTORS AND THE JUSTICE DEPARTMENT

December 2017 report

"60 Minutes" partnered with the Washington Post again in December 2017 and found another disturbing story from inside the DEA. After two years of painstaking inquiry, DEA investigators built the biggest case the agency had ever made against a drug company: McKesson Corporation, the country's largest drug distributor

"The issue with McKesson was they were providing millions and millions and millions of pills to countless pharmacies throughout the United States, and they did not maintain any sort of due diligence," David Schiller, a former DEA assistant special agent, told correspondent Bill Whitaker.

But Schiller's investigators hit a roadblock in Washington D.C. when they tried to hold McKesson accountable. Schiller says attorneys for the DEA and the Department of Justice were intimidated at the thought of going against McKesson and its high-powered legal team.

In the end, instead of the $1 billion fine that Schiller and his team wanted, McKesson was fined just $150 million.

"How do you do that?" Schiller told Whitaker. "No. Put them in jail. You put the people that are responsible for dealing drugs, for breaking the law, in jail. Nobody's in jail. They wrote a check."

The doctors and the drug manufacturers

September 2018 report

Drug distributors have been delivering huge numbers of pills to pharmacies, and pharmaceutical lobbyists have pressured Congress to let them off the hook. But what about the doctors who write prescriptions for huge quantities of the highly addictive drug? And the manufacturers who supply the distributors? In September 2018, Whitaker investigated two additional pieces of the puzzle.

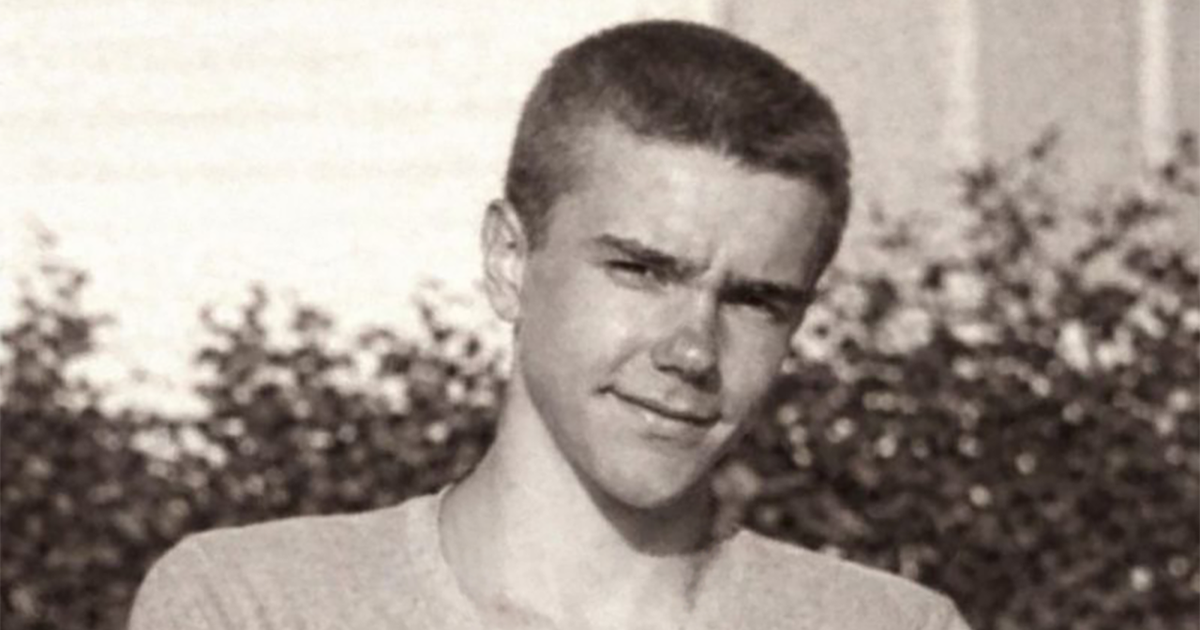

He spoke with Florida physician Barry Schultz, who was sentenced in July 2018 to 157 years for his role in the opioid crisis. Schultz told Whitaker he has become a scapegoat.

"I was one of hundreds of doctors that were prescribing medication for chronic pain," Schultz said. "In my mind, what I was doing was legitimate."

But DEA records show that in 2010, Schultz prescribed one patient more than 23,000 oxycodone pills in an eight-month period — more than 100 pills a day to a single person. During one 16-month period, his in-office pharmacy dispensed 800,000 opioid pills.

As for the manufacturers, two-thirds of all the oxycodone in Florida came from just one company: Mallinckrodt. Five hundred million of their oxycodone pills were distributed in Florida between 2008 and 2012.

Jim Rafalski led a DEA investigation into Mallinckrodt and discovered drug orders from distributors that the company knew about — and should have flagged as suspicious. But after the DEA turned over its evidence to the Justice Department, things took a familiar turn. Fearing an uncertain legal battle, government lawyers decided to settle with Mallinckrodt and fined the company just $35 million. The penalty amounts to less than one week of Mallinckrodt's annual revenue.

When Whitaker asked what role he feels Mallinckrodt has played in the opioid crisis, Rafalski was unambiguous in his response: "They're responsible."

The FDA

February 2019 report

Responsibility for the opioid epidemic may ultimately point to the Food and Drug Administration — and a fateful decision the FDA made all the way back in 2001.

Drug manufacturer Ed Thompson spent decades producing opioids for the pharmaceutical industry. He told "60 Minutes" that, when the FDA first approved Oxycontin in 1995, science only showed that the drug was effective when used in the short term.

But Thompson said the pharmaceutical industry pressured the FDA. Six years later, in 2001, the FDA decided to change the label for Oxycontin, expanding the use for almost anyone with chronic pain.

"60 Minutes" obtained a court order to get the minutes to secret meetings in 2001 between the FDA and Purdue Pharma, the maker of Oxycontin. The documents reveal that the FDA bowed to Purdue Pharma's demands to ignore the lack of science supporting long-term use and changed the Oxycontin label to "around the clock ... for an extended period of time." This gave big pharma the green light to push opioids to tens of millions of new pain patients nationwide.

Does Thompson now believe the FDA ignited the opioid crisis?

"Without question," he told Whitaker, "they [started] the fire."