The Lusitania disaster: A "maritime grassy knoll"

A century-old mystery beneath the waves remains unsolved as we enter this New Year. It involves the sinking of the ocean liner Lusitania during the First World War. Martha Teichner takes us back:

Before air travel, the departure of a great liner was considered news ... and Cunard's Lusitania was the greatest, the fastest, the most luxurious liner afloat on May 1, 1915 as she prepared to leave New York City for Liverpool.

It was news that the glamorous and rich Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt was aboard, a member of the "Just Missed It Club" (people who had booked on the Titanic, but cancelled at the last minute).

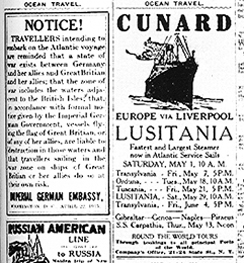

And it was news that in the morning papers that day, Germany -- at war with Great Britain -- published a warning, that vessels flying the British flag, or the flag of any of her allies, were subject to attack as they passed through the waters off the British Isles.

"Even though it made no mention of the Lusitania, it was widely interpreted to be aimed at the ship," said Erik Larson, the author of the New York Times bestseller, "Dead Wake," about the Lusitania.

"The prevailing view was that the Lusitania was too big, too fast to ever be caught by a German submarine," he told Teichner. "Also, there was this other idea that no German commander would try to sink it in the first place, because it was a passenger liner."

But on May 7, at 2:10 p.m., in sight of the Irish coast, the Lusitania was struck by a German torpedo. Moments later, there was a second explosion. She sank in just 18 minutes.

Eleven hundred ninety-eight of the nearly 2,000 people on the ship died -- more than 120 of them Americans.

The wreck is still down there, in 300 feet of water. Boat captain Carroll O'Donoghue feels its presence.

"You remember the tragedy of it all, really," O'Donoghue said. "Perfectly clear day, just like today."

For a 1994 documentary, National Geographic interviewed survivors of the Lusitania. "All I could see was heads bobbing up and down," said one woman.

"It was like half a circle of people moaning in the water," another survivor said. "There was just a moan, a constant moan, and it gradually got less and less."

Eoin McGarry has dived the wreck nearly 50 times. "When I look up at the surface, I can see bodies raining down," he said. "You could see what it was like. You can hear the screams."

The torpedo hit just behind the bridge on the starboard side. The ship tilted so far, so fast, only six lifeboats successfully made it into the water.

Naval vessels in the area were ordered not to go near the site for fear they would be torpedoed, too, so small boats made their way from Queenstown (now called Cobh), 31 miles away. Some rescuers had to row the entire distance.

"My grandfather raced down to the office, was immediately involved in the rescue operation, getting anybody who had a boat to go out," said Courtney Murphy.

Courtney's grandfather, Jerome Murphy, was the Cunard Line manager in Queenstown. "He had to organize, to commandeer rooms in the hotels where the people, the survivors could be put up."

Ccourtney Murphy's father, then a small boy, watched as the rescue boats returned. "The bodies as they came in in the boats, would've been in whatever clothes they had on them," Courtney said, "and then they were covered in shrouds or in sheets." The sight of lines of bodies laid out along the footpath was an indelible memory for him.

There were 764 survivors. Among the dead: Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt.

Today, in Cobh, there's a monument along the route the funeral procession took to the town cemetery where the Lusitania dead were buried in mass graves. Mourners as far as the eye could see paid their respects.

Was the sinking of the Lusitania just bad luck, or something more sinister? Her captain, William Thomas Turner, believed she would have a British naval escort into port. None appeared. The British Navy didn't tell Capt. Turner that U-20, the submarine that sunk her, was out there -- something it knew, because Germany's code books had been captured and then decoded at a top-secret facility called Room 40.

"One explanation is that Room 40 was absolutely top secret and, by God, they were gonna keep it that way," said Larson. "But another explanation is that it would not hurt the British effort if the Lusitania were sunk and Americans were killed, because it might draw America into the war."

Winston Churchill oversaw Room 40. Then head of the British Navy, he was on record hoping for an incident that would drag the U.S. into the war -- something that wouldn't actually happen for another two years.

"There's no 'smoking memo,' if you will, that says that Churchill or the Admiralty deliberately put the Lusitania in harm's way," said Larson. "There is, however, a body of evidence that, if you look at it, it is really damning."

No one has ever been able to inspect the underside of the wreck, where the answer to the question "What caused the second explosion?" may lie.

The Irish government has only allowed diver Eioin McGarry to bring up artifacts from the Lusitania that were lying on the sea floor or were in the bridge area.

"If you could imagine the whole ship lying on her side, the starboard side is underneath," said McGarry. "And sadly, because she's lying on the torpedo wound, we can't see exactly."

McGarry, for one, doesn't believe the accepted conclusion that the second explosion was caused by the rupture of the ship's main steam line. She was carrying small arms munitions. But were there other explosives aboard?

"I still think that there was, and she was carrying contraband," said McGarry. "Something substantially caused that second explosion.and I do believe that there is somebody out there who does know."

Or not.

The Lusitania remains fodder for conspiracy theorists.

"It's the maritime grassy knoll," said Larson. "There are so many miraculous or nearly so things that happened, that leaves room for people to say, 'Oh, well, that can't be it." I mean, here's this ship that sank in 18 minutes. It's just not possible, right?"

One hundred years later, as time takes its toll, the truth only become more elusive.

- "Scariest ship": Robert Ballard on dangers of exploring Lusitania wreck ("60 Minutes," 11/29/09)

For more info:

- "Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania" by Erik Larson (Crown); Also available in Trade Paperback, eBook, Digital Audio Download, and Digital Audio CD formats

- Cobh Heritage Center, Cobh, Ireland

- The Lusitania Resource (rmslusitania.info)

- lusitania.net

- The Lusitania Disaster (Library of Congress)