The Lincoln Memorial at 100: How a monument to history became a part of history

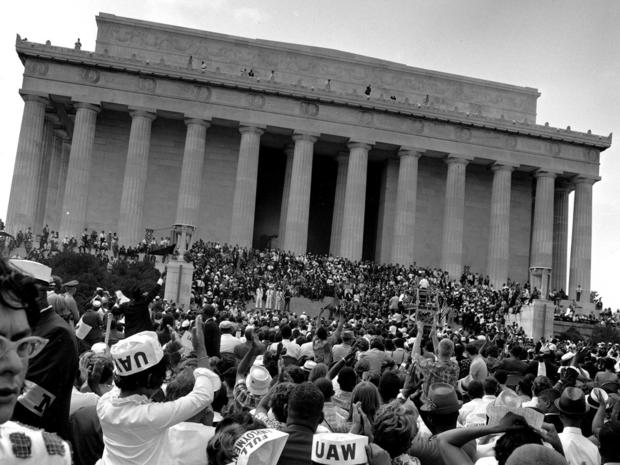

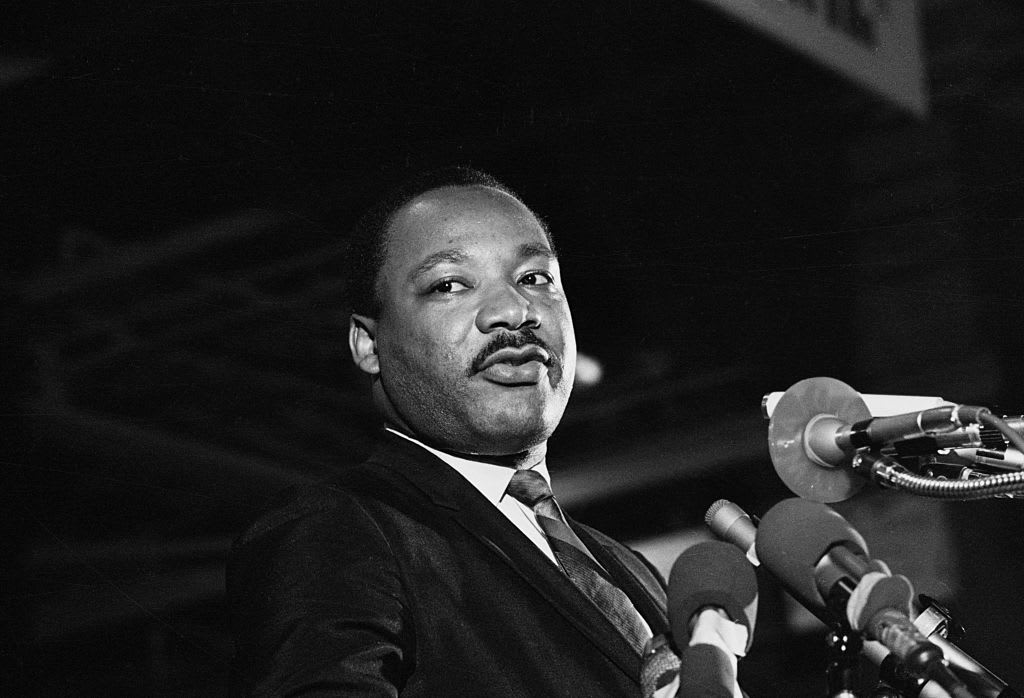

In 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial with a dream – and in the years since, millions have come here to make their own voices heard.

According to Mike Litterst, chief of communications for the National Mall, "The Lincoln Memorial, more than any other of the monuments and memorials we oversee, has become a historic site in its own right, a symbol of where you go to exercise your First Amendment right."

But Litterst said creating a stage for protest wasn't part of the Memorial's original design: "It is on a straight line axis from the Capitol to the Washington Monument, to where the Lincoln Memorial was built. Henry Bacon, the architect, envisioned that at the far end of the of the Mall, you have the Capitol Building, which represents the government, and here you have the Lincoln Memorial, Abraham Lincoln, the savior of that government."

Arlington Memorial Bridge is a symbolic link connecting the Memorial and the Mall to the formerly Confederate Virginia.

But imagine if the Lincoln Memorial looked like this … or this!

Ultimately It was preeminent American architect Henry Bacon's Neoclassical design that was selected, modeled after the Parthenon in Athens, all to celebrate a man born in a log cabin.

There are 87 steps to the Memorial – that's right: four-score-and-seven steps leading up to Lincoln, and to engravings of his Gettysburg Address and Second Inaugural Address. And those with an eagle eye can even spot a typo!

As Litterst pointed out to correspondent Faith Salie, "The word 'future' was mistakenly carved with an E to start, and had to be sort of puttied or filled in, to make the E back into an F" – a charming accident buried in a very deliberate design.

The memorial was symbolically hewn from rock that hailed from all parts of the United States – stone from Massachusetts, Colorado, Tennessee – while Lincoln himself is carved of Georgia marble. The design scheme was unity, so there is almost no mention of the actual cause of the Civil War, slavery.

Scott Sandage, professor of American history at Carnegie Mellon University, notes, "By saying nothing about slavery, you avoid the rubbing of old sores. So, they intentionally build a memorial that has no references in it to enslavement or to the end of slavery, except for the eloquent references that Abraham Lincoln himself made in his Second Inaugural Address." ["American slavery is one of those offenses which in the providence of God … He now wills to remove."]

On May 30, 1922, the memorial was dedicated by former President Howard Taft in front of a large segregated crowd, one that included Lincoln's son, Robert Todd Lincoln. The only African-American speaker of the day, Dr. Robert Moton, head of the Tuskegee Institute, even had his speech censored. Only the Civil War Union veterans were seated Black next to white, as they had fought on the battlefield.

Sandage said, "Historically Black newspapers like the Chicago Defender began to run editorials that said the Lincoln Memorial has been opened, but it has not been dedicated, because the memorial itself didn't say anything about slavery."

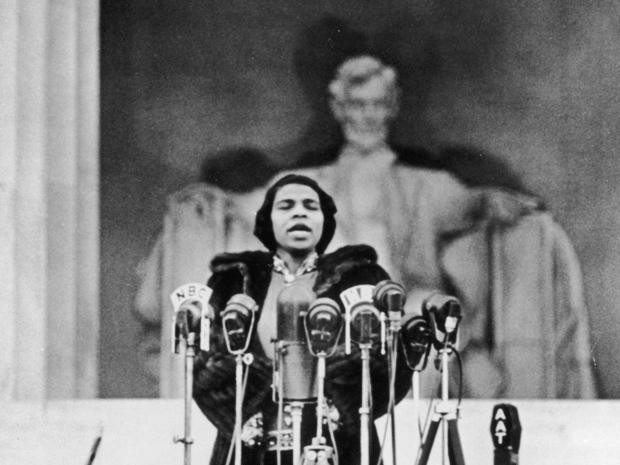

Perhaps the memorial's true dedication came in 1939, when African-American superstar contralto Marian Anderson (whom famed conductor Arturo Toscanini called "the voice of the century") performed on its steps, according to professor Salamishah Tillet of Rutgers Newark: "I would say when she sang, the people think of as the beginning of the modern civil rights movement."

Anderson had wanted to perform at the capital's largest indoor venue, Constitution Hall. But, said Tillet, "She was turned down by the Daughters of the American Revolution, who said that only white performers are allowed access there."

Instead, she sang on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, for an integrated crowd of 75,000 and a radio audience of millions.

When Anderson began to sing "My Country, 'Tis of Thee," she changed the words: Instead of singing, "O thee I sing," she sang "To thee we sing."

Tillet said, "And she becomes an American voice of democracy in that moment. Performing in front of [Lincoln] was also a way of writing Black people back into the history of Lincoln."

And turning the steps of the Lincoln Memorial into a stage.

Sandage said, "If you walk up those steps, I think it's impossible not to think of Martin Luther King in addition to thinking about Abraham Lincoln; not to think of contralto Marian Anderson. And so, in an amazing twist, the Lincoln Memorial became a place for rewriting the history that it was intended to erase.

"It was intended to forget about racial divides, and it became a place for remembering them, and trying to heal them."

For more info:

- Lincoln Memorial (National Park Service)

- National Mall and Memorial Parks, Washington, D.C.

- Scott Sandage, professor, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pa.

- Salamishah Tillet, professor, Rutgers University, Newark, N.J.

Story produced by Anthony Laudato. Editor: Emanuele Secci.