The historical roots of Trump's favorite phrases

From "Mission Accomplished," to "America First," President Trump has a habit of revamping memorable phrases from history. A Saturday morning tweet from the president served as yet another example.

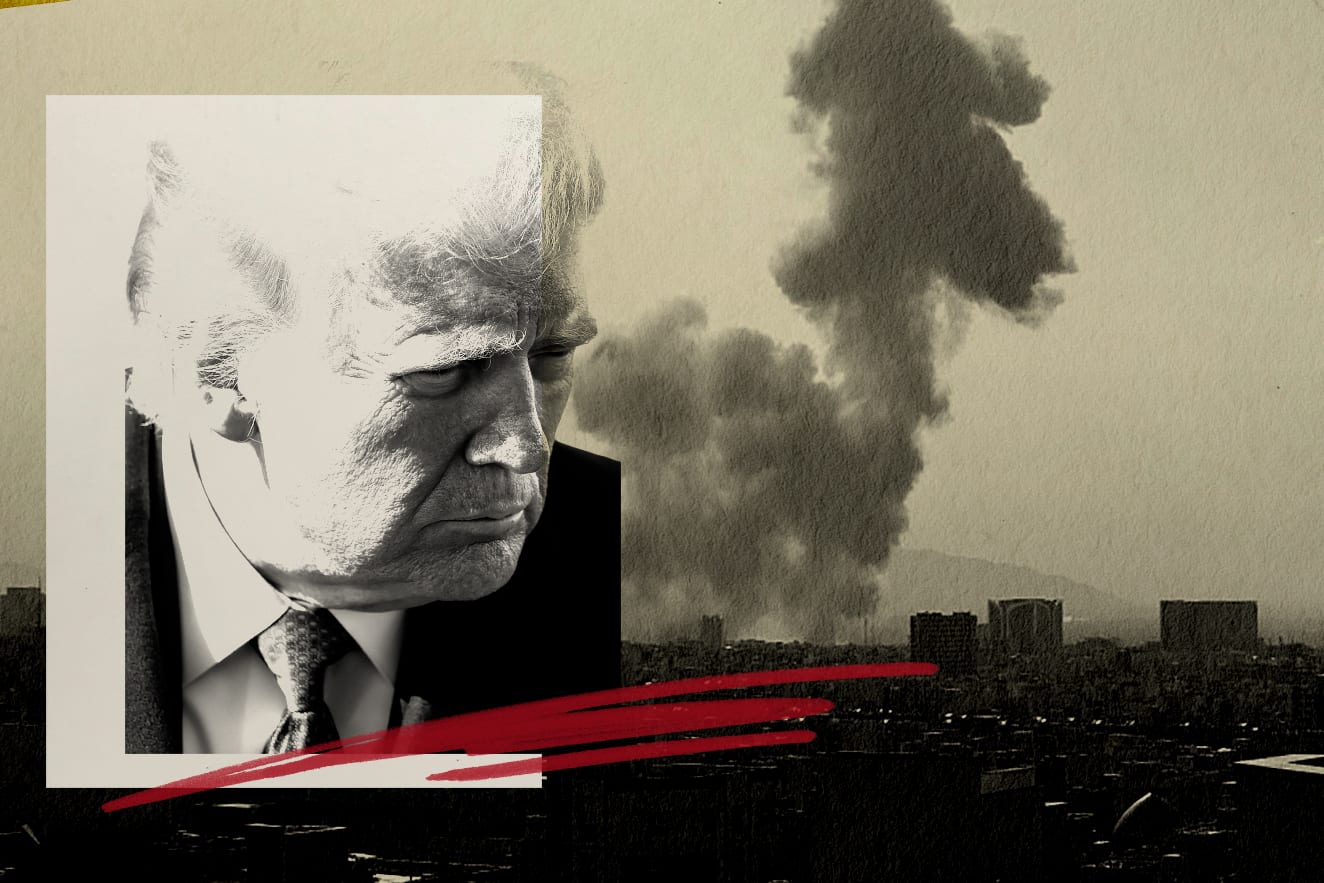

"A perfectly executed strike last night. Thank you to France and the United Kingdom for their wisdom and the power of their fine Military. Could not have had a better result. Mission Accomplished!" Mr. Trump tweeted early Saturday, after the U.S., U.K. and France launched airstrikes against Syrian targets.

"Mission accomplished" is the same phrase former President George W. Bush infamously used in 2003, after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. Bush was addressing sailors aboard a ship alongside a "Mission Accomplished" banner. Weeks later, it became apparent that Iraqis had organized an insurgency, and U.S. forces remained in the country for years.

Here are some of the phrases Mr. Trump has used, and the history behind them.

"Mission Accomplished"

Mr. Trump's tweet Saturday, in which he declared the overnight strikes in Syria a success, reminded many of Bush's use of the phrase in 2003.

In May that year, Bush said from the USS Abraham Lincoln that major combat operations in Iraq had ended. With a "Mission Accomplished" banner behind him — a banner he later blamed on the Navy and not his own staff — he declared victory in Iraq.

"America sent you on a mission to remove a grave threat and to liberate an oppressed people, and that mission has been accomplished," Bush said at the time.

The vast majority of casualties, both civilian and military in Iraq, occurred after that speech.

Years later, Bush would call the "mission accomplished" speech a "mistake." When Mr. Trump tweeted "Mission Accomplished" Saturday, White House press secretary under Bush, Ari Fleischer, said he would have "recommended" avoiding that phrase.

"Enemy of the American People"

That's what Mr. Trump called the media in a February 2017 tweet, shortly after taking office. And while the phrase "enemies of the people" dates back to the Roman Empire and is probably today most associated with the deprivations of Soviet communism, it was Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen who really gave it wide currency in 1882.

Ibsen's "An Enemy of the People" deals with a doctor, Thomas Stockmann, who discovers his local town's famed baths are poisoning people. The doctor initially enlists the help of the local liberal paper to uncover his findings, but due to political pressure the publisher switches sides and proclaims the doctor "an enemy of the people." The doctor's life is destroyed.

Over at The Daily Beast, Michael Tomasky noted the parallels between the play and the president's use of the term. "With Trump having declared the press the enemy, it would fit our exact circumstances today a little better if the newspaper had stood courageously with Stockmann," Tomasky wrote. "On the other hand, the portrait of media timidity is all too apt, is it not?"

Sen. Flake raised eyebrows by connecting Mr. Trump's words to Joseph Stalin, although it's true Soviet dictator is widely associated with use of the phrase "enemies of the people." And it's true that, while denouncing Stalin in 1956, Krushchev announced that the phrase should no longer be used.

Other fans of variations of "enemy of the people" include Maximilien Robespierre, Vladimir Lenin and Chinese despot Mao Zedong, who was likely the most murderous dictator of the 20th Century.

"America First"

Before it was Mr. Trump's signature slogan, "America First" was the rallying cry of the "isolationists" who endeavored to keep the U.S. out of World War II. Staying out of the war was a popular cause before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and enjoyed the support of everyone from hard-right conservatives to American communists, who only joined the pro-war chorus after Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union.

The most notable of the America First crowd – which included members of the Kennedy family, Henry Ford, and a number of sitting U.S. senators – was probably Charles Lindbergh, the famed aviator who in 1927 became the first man to fly alone across the Atlantic.

Lindbergh was one of the most famous people in America at the time, and his reputation never truly recovered from his involvement with the America First movement, his praise of German air power before the war, and his open flirtation with anti-Semitism. "If I should die tomorrow, I want you to know this, I am absolutely convinced that Lindbergh is a Nazi," an irate President Roosevelt wrote to his treasury secretary, Henry Morgenthau, in 1940. When Lindbergh tried to sign up for the Army Air Corps once the war began, the White House blocked his request, although he eventually was able to fly combat missions in the Pacific.

Needless to say, the cause of America First did not age well in the eyes of historians. But it has been defended by former Pat Buchanan, a former aide to Presidents Nixon and Reagan whose runs for the presidency in 1992 and 1996 arguably set the template for Mr. Trump's 2016 run.

"What America First means is we put the national interests of the United States and the wellbeing of our own country and our own people first," Buchanan told NPR in January 2017 while defending Mr. Trump's use of the phrase. "Our foreign policy, first and foremost, should be focused on the defense of American freedom, security and rights."

However, in a little irony of history, Mr. Trump accused Buchanan of being "a Hitler lover" when they both briefly vied for the Reform Party nomination in 2000, and used Buchanan's anti-war sentiments to help buttress the argument.

"Silent Majority"

"The Silent Majority Stands with Trump" was a common sign at Mr. Trump's raucous rallies during the 2016 campaign. But the "silent majority" is most associated with Nixon, who famously used the phrase in a November 1969 speech castigating left-wing demonstrators. Nixon wrote the speech himself, but it was Buchanan, then a White House speechwriter, who introduced him to the phrase "Silent Majority."

"Nixon had used a phrase, the 'Silent Majority,' that would resonate down through the decades, a phrase I had given him in August 1968," Buchanan wrote in his 2017 memoir "Nixon's White House Wars."

"I had come back from the Democratic convention in Chicago, where he had sent me, and, after witnessing the riot in Grant Park, advised Nixon on what to say on his first foray of the fall campaign, back to that same city: 'I would use the demonstrators, the worst of them…as a foil for RN's argument. I would allude…to the Silent Majority, the quiet Americans whose cause is just. They have a right to be heard.' Nixon had underlined 'Silent Majority.'"

The speech was a hit with the public, and would become one of the most famous of Nixon's presidency. "The new majority of northern Catholics and southern Protestants has moved away from the party of their father's, toward Richard Nixon's Republican Party," Buchanan wrote about the aftermath of the speech.

Political strategist Roger Stone, who worked for both Nixon and Mr. Trump, told Business Insider last year about how the two Republican presidents connected with the same voters. "That they appeal to the common man, the silent majority," Stone said. "The blue collar white Democrat that was part of the Nixon coalition is now part of the Trump coalition."

"Law and order"

"I am the law and order candidate," Mr. Trump said in July 2016, just days after a gunman murdered five police officers in Dallas. Indeed, "law and order" became a common refrain for Mr. Trump, and once again it's a phrase that harkens back to Nixon.

The chaos of 1968 – a year of high crime, widespread riots, and the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy – provided the backdrop for Nixon's second presidential campaign. Taking a page from 1964 Republican nominee Barry Goldwater, Nixon focused squarely on law-and-order issues, and in the process developed a playbook that would be used by Republican candidates for decades.

Critics said appeals to "law and order" were thinly veiled appeals to the racial anxieties of white voters, but America really was a more violent place by the late 1960s. However, when Mr. Trump ran as a law and order candidate in 2016, crime rates had fallen dramatically across the country.

Still, Mr. Trump's message resonated among voters who worried the country was becoming undone. When he ran for president, relations between police and minority communities had greatly soured, and riots in cities like Baltimore and Ferguson, Missouri were becoming more commonplace. Mr. Trump also highlighted the porous nature of America's southern border, repeatedly insisting that drugs and criminal gangs were flowing from Mexico while Democrats in Washington looked away. The opening night theme of the GOP's 2016 convention was "Make America Safe Again."

As was the case with Nixon, liberals portrayed Trump's focus on law and order as a series of racist dog-whistles. "[B]oth Nixon and Trump tapped into ugly and real sides of the American character—fear of outsiders, anger at a changing world," attorney and Trump critic Jeffrey Toobin wrote in The New Yorker in April. "When Trump finally ran for President…he adopted more of Nixon's tropes than Reagan's. Nixon built his Presidential campaign around the slogan of law and order, and so did Trump."