The historic tension between black and blue, and the rise in calls to "defund the police"

The signs are everywhere: Defund, demilitarize, abolish – calls for wholesale changes in policing that may have seemed unthinkable just a few weeks ago.

"I think we need to understand that law enforcement is an actual governmental agency that needs to be held accountable and needs to have less power over our communities," said Patrisse Cullors, a lifelong activist and co-founder of Black Lives Matter. She recently co-authored a memoir about the movement, "When They Call You a Terrorist."

"We have sort of created this idea that law enforcement is the community, and they are not," she said. "They have been a deeply repressive force. They haven't just killed black communities; they've humiliated, they've abused, they violated, over and over again."

Black Lives Matter started in 2013, after the killing of Treyvon Martin in Florida. It has become more prominent as the number of killings of black people continued: Michael Brown in Ferguson … Breonna Taylor in Louisville … George Floyd in Minneapolis … Rayshard Brooks in Atlanta.

Correspondent Jeff Pegues sked, "When you're saying 'black lives matter,' are you saying that black lives matter more than other lives?"

"Great question; we're saying black lives matter, too," Cullors replied. "What we're really saying is, all lives won't matter until black lives matter."

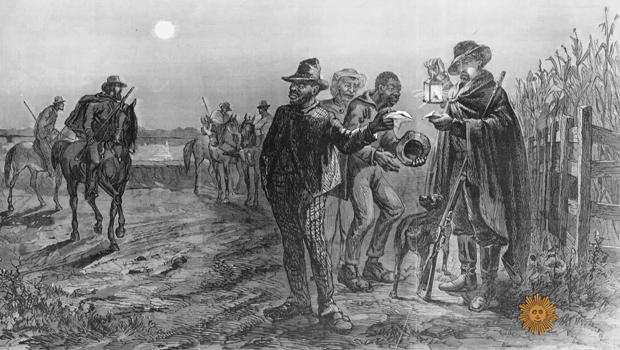

Gary Potter, a criminology professor at Eastern Kentucky University, has written about the history of policing in America which, in the South, dates back to the early 1700s and the slave patrols.

Pegues asked, "Has there always been this tension between the black community and police?"

"Yes, yes, and for good reason," Potter replied. "Slave patrols were designed to perform three functions: To apprehend runaway slaves; to provide deterrence against a possible slave revolt; and also to create a kind of atmosphere of terror around plantations, so that there were no disorders, no uprisings."

In the 1800s, those slave patrols evolved into police departments, while in the North, departments grew out of colonial watch programs.

The 1900s saw police (in some places with the help of the Ku Klux Klan) cracking down on black Americans, enforcing racial segregation, and suppressing calls for equality.

That tension between black and blue still exists to this day.

"The black community is over-policed for minor infractions that would draw virtually no attention anywhere else," said Potter.

Statistics show that black people are imprisoned at five times the rate of whites, and are three times more likely than whites to be killed by police.

Pegues asked Cullors, "So, are you calling all police officers racist?"

"No," she replied. "This is not an issue of the individual. This is an issue of a system that has been in place for a very long time that is wedded to institutional racism. So, it's less about the individual. Although many people are asking for individual officers who cause harm and violence to be accountable, we're talking about systems. And that is very, very important for people to understand."

Terrence Cunningham most definitely does not want to "abolish" the police. He's a former police chief in Wellesley, Massachusetts. But, he told Pegues, "I think that there are things that we can absolutely do better."

In 2016, when he was President of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, he delivered a speech that he hoped would improve police-community relations: "The first step in this process is for the law enforcement profession and the IACP to acknowledge and apologize for the actions of the past and the role that our profession had played in society's historical mistreatment of communities of color."

It was a bold but controversial acknowledgement that you can't change the future without admitting the mistakes of the past.

Cunningham told Pegues, "A police officer, young officer comes on the job today, and they feel they have, you know, complete objectivity, that there's no implicit bias, that there's no racism built into their thought process. And then you've got the lens of the African American community that have been, you know, oppressed at the hands of the police for at least since the late 19th century to early 20th century. So, when that officer makes that car stop at 2 o'clock in the morning, they have to understand that history. And when they put that uniform on, they put all that history on with it.

"If we don't understand that history, then we are doomed to repeat it."

If that's the past, here's how Cunningham looks to the future:

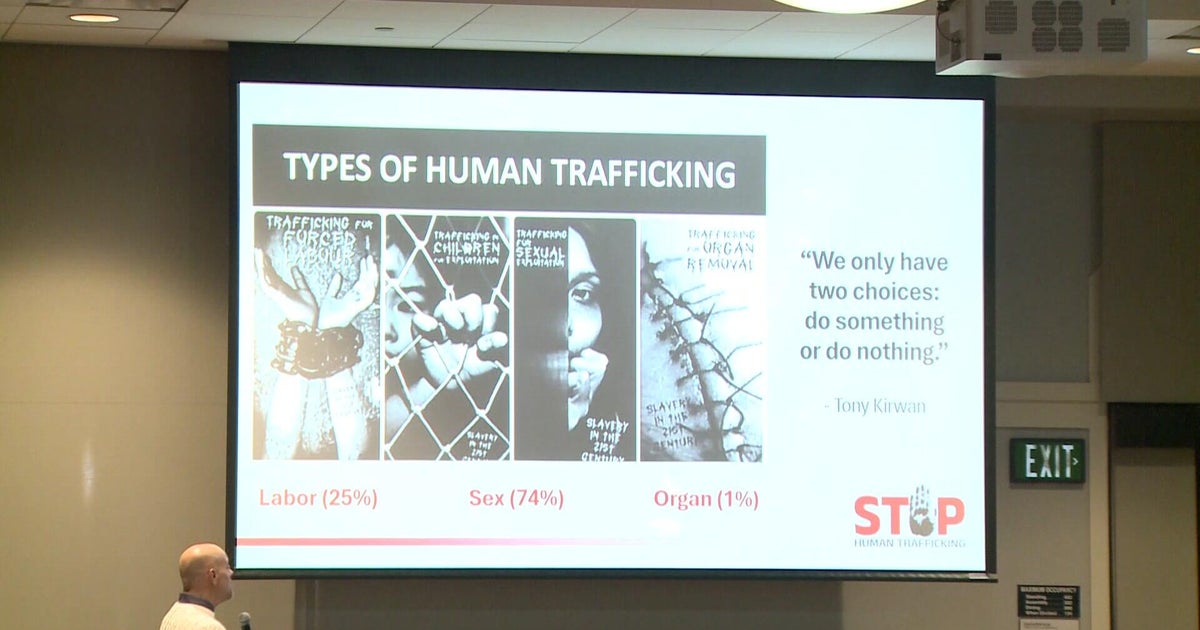

"We need to change the way we recruit people," he said. "Right now, we still recruit like we're, you know, 90% law enforcement and 10% social services, where quite frankly, it's just the opposite now. It's 90% social services and 10% law enforcement actions that we take."

And that might get to the heart of a large part of the "defund the police" movement: the idea that police are spending most of their time, not preventing or solving crimes, but on what are essentially social issues.

Cullors asked, "Why is your local law enforcement the first responder to mental health care needs? Why are they first responder to homelessness? Why are they the first responder to drug and alcohol abuse? And oftentimes, what we've seen over and over again is people calling the police specifically around mental health care crisis, and then dying because of it."

There are actually more police in this country than all types of social workers combined.

Potter said, "We need to fully fund, more fully fund education, mental health services, drug rehab and education, and simple health services, so that someone with an alcohol problem doesn't get shot in the back at a Wendy's restaurant. And to do that, we probably need to remove some of the funding from police and move it to other services."

Across the country, reform proposals include efforts to reduce the power of police unions, which are often obstacles to change.

But activists point hopefully to programs like CAHOOTS in Eugene, Oregon. There, 911 operators routinely dispatch social workers and medics to calls for help, instead of an officer with a gun.

Cullors said, "We want to release our addiction to an economy of punishment and actually lean into an economy of care. And we believe that our communities will be better off because of it."

For more info:

- Black Lives Matter

- "When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir" by Patrisse Khan-Cullors and Asha Bandele (St. Martin's Press), in Hardcover, Trade Paperback, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon

- Dr. Gary Potter, School of Justice Studies, Eastern Kentucky University, Richmond, Ky.

- CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets), Eugene, Ore.

Story produced by Alan Golds and Young Kim. Editor: Lauren Barnello.