The Herbert Hoover you didn't know

In late October of 1929, after years of rising to dizzying heights, the stock market collapsed, ushering in one of the longest and most painful chapters in American history.

Herbert Hoover had been president for less than a year. It was he who called it a "depression."

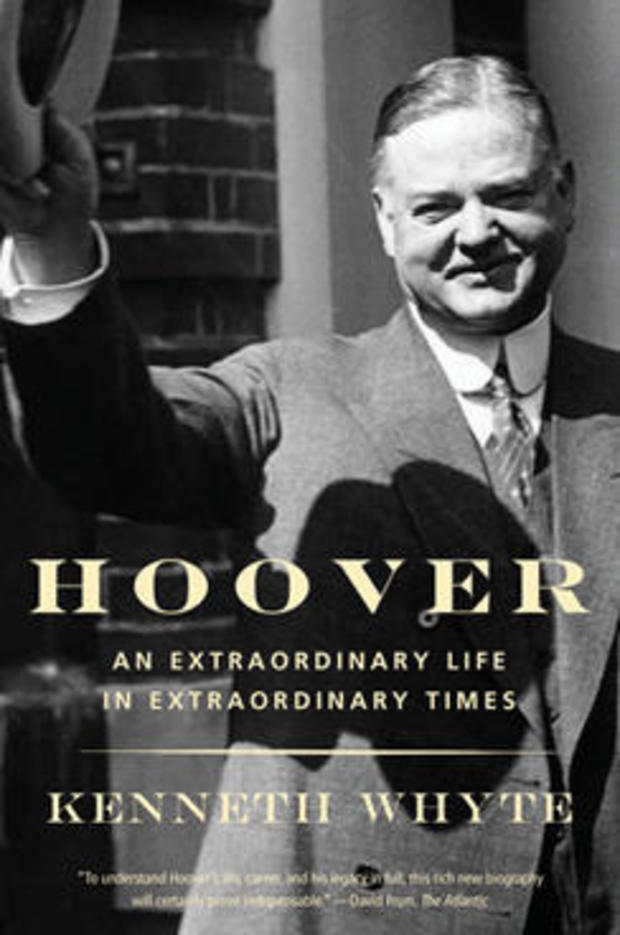

"Before that, they always called them panics; he liked the word depression," said Kenneth Whyte, author of a biography of Hoover. "I don't think he anticipated that it would be one that would be stuck with him the rest of his life."

And that's no exaggeration: Consider the 1977 Broadway musical "Annie," in which a chorus of slum-dwellers mockingly "thanks" the president:

We'd like to thank you, Herbert Hoover

For really showing us the way

We'd like to thank you, Herbert Hoover

You made us what we are today

Correspondent Mo Rocca asked, "Did the musical 'Annie' annoy you?"

"What it did, it stoked in me this, like, burning dissent, like, 'These people don't know the whole story!'" said Margaret Hoover, host of PBS' "Firing Line" and the great-granddaughter of the 31st president. "This man lived 90 years, and he is judged for four of them."

And that's a shame, since Hoover's life before entering the White House was quite simply remarkable. By the way, Margaret's choice to play Hoover in the movie? "Leonardo DiCaprio," she said.

Hoover, a Quaker, was born in 1874, of modest means, in the village of West Branch, Iowa. He, his parents and two siblings shared a tiny, two-room house. Park Ranger Adam Prato, at the Herbert Hoover National Historic Site, said, "His father died when Herbert was about six. And then his mother died a few years later, when he was nine"

The orphaned Bert, as he was known, was put on a train and sent 2,000 miles west, to live with his uncle's family in Newberg, Oregon.

"Their only son was killed in a very tragic hay wagon accident," Sarah Munro, director of the Hoover-Minthorn House in Newberg, said.

"So, Herbert was essentially sent to Oregon to kind of replace the son that his uncle and aunt had lost?" asked Rocca.

"In some ways yes. But he definitely had to earn his board here."

It was not, Munro said, a particularly affectionate home. Absent the unconditional love of his birth family, Bert threw himself into work, determined to win respect and reward. Whyte said, "He had a deep, deep need to prove himself. He also had an abundance of physical energy and intellectual energy, and it needed outlets."

Hoover was accepted into the very first class of Stanford University, where he studied geology – preparation for a career as a mining engineer. His talent for turning around unproductive mines made him very much in demand the world over.

"In his early 20s he's running gold mines in Australia," said Whyte. "In his mid-20s he's off in China."

His relentless drive, and his willingness to do whatever was necessary, paid off. He made several fortunes in his twenties, and retired at the start of the First World War with about $3-4 million in assets.

Now, if Herbert Hoover's obituary had been written in 1914, he would have been remembered as a talented engineer-turned-business magnate. But his response to World War I turned him into something greater.

When the war broke out, 120,000 Americans were stranded in Europe. Hoover, a private citizen living in London, assembled the ships to get the Americans home. He followed this feat with an even more stunning one.

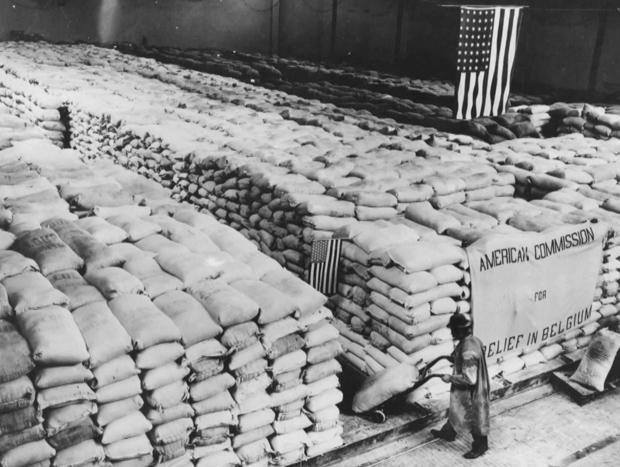

Germany invaded Belgium, and cut off Belgium's food supply. The U.S., still neutral, was reluctant to get involved. "Everyone is arguing they didn't have responsibility to feel the Belgians," noted Whyte. "Hoover said, 'I'll feed them, let me through,' and pretty much bullied his way through both lines."

Hoover himself convinced both the British and Germans to allow delivery of millions of tons of food to the starving Belgians. Whyte said, "He was dealing as though he were his own State Department."

Tom Schwartz, director of the Hoover Presidential Library and Museum, said, "As he put it, 'The feeding must go on!'"

Hoover and the Commission for Relief in Belgium ended up feeding between seven and eight million people. He would become known as "The Great Humanitarian." "I still get emails and letters from people Hoover fed," said Schwartz.

After the war, Hoover went from saving European lives to modernizing American lives. As Secretary of Commerce under Presidents Harding and Coolidge, Hoover set standards for everything from electric light sockets to milk bottles. (Get this: the dairy industry had previously had 42 different sized containers of milk. Hoover got them to do it by pint, quart, half-gallon and gallon.)

And he brought order – and safety – to traffic lights. "He standardized it so red meant stop, green meant go. He did that," said Schwartz.

But wait … there's more! Hoover helped lay the groundwork for the commercial aviation industry, and oversaw development of the Hoover Dam. As the country's unofficial innovator-in-chief, Hoover was the very first person to appear on a live television broadcast, in 1927.

He was, Rocca noted, a very modern man.

And in his spare time, Hoover and his wife, Lou – one of the first women in America to earn a degree in geology – translated an ancient mining text from the original Latin. The translation, published in 1912, became an industry standard, and is still in print today.

When the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 displaced hundreds of thousands, it was a foregone conclusion that Hoover would lead the relief effort, and he rode the resulting wave of adulation to the Republican nomination for President in 1928 – and a landslide victory.

At his inauguration Hoover said, "I have no fears for the future of our country. It is bright with hope."

Only eight months later came Black Tuesday. In 1932 Franklin Delano Roosevelt would sweep Hoover out of office after a single term.

Rocca asked, "The Great Depression lasted twice as long under FDR than it did under Hoover. So, why does Hoover get stuck owning the Depression?"

"Because when Roosevelt came in, he labeled it the Hoover Depression," said Whyte," and he never stopped calling it the Hoover Depression throughout the whole of his Presidency."

It was FDR's successor, Harry Truman, who welcomed Hoover back into public life – and Hoover, said Whyte, "is enormously grateful for the gesture."

In 1962, on Hoover's 88th birthday, his presidential library was dedicated, only feet from the humble dwelling in which he'd been born. Former President Truman delivered remarks, saying, "What more can a man do? His record, and his career, is unequaled in the history of this country."

Whyte said, "By the end of his life, he was rather proud of the fact that he is the only living American with a depression named after him! He could joke about it, but it took a long time."

For more info:

- Hoover-Minthorn House Museum, Newberg, Ore.

- Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum, West Branch, Iowa

- "Firing Line with Margaret Hoover" (PBS)

- "Hoover: An Extraordinary Life in Extraordinary Times" by Kenneth Whyte (Knopf), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon

Story produced by Mary Lou Teel.

More presidential history from Mo Rocca:

- Andrew Johnson: The unfortunate president

- Chester A. Arthur and the original "birther" controversy

- Worst president ever: The ignominy of James Buchanan

- The long and short of President William Henry Harrison

- James Polk and America's "Forgotten War" south of the border

- President John Tyler's great genes

- How doctors killed President James Garfield

- President Warren Harding: Sex, scandal and death in the White House

- Ulysses S. Grant's last battle

- The passions of Woodrow Wilson