The forger who saved thousands of Jews from the Nazis

It was Adolfo Kaminsky's dry cleaning know-how that first got the attention of the French Resistance. In Paris during World War II, the resistance had been desperately trying to figure out how to erase a permanent blue ink from official documents. If they could figure it out, they could modify Jews' original documents as well as creating new ones.

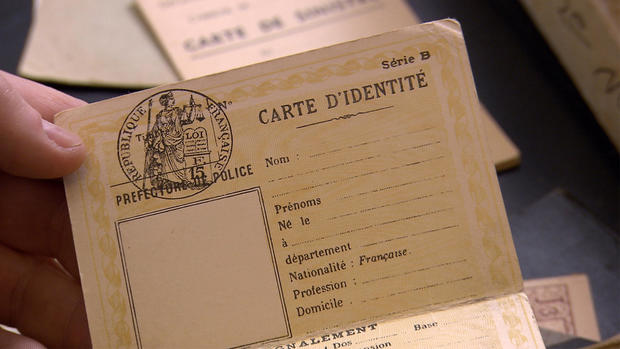

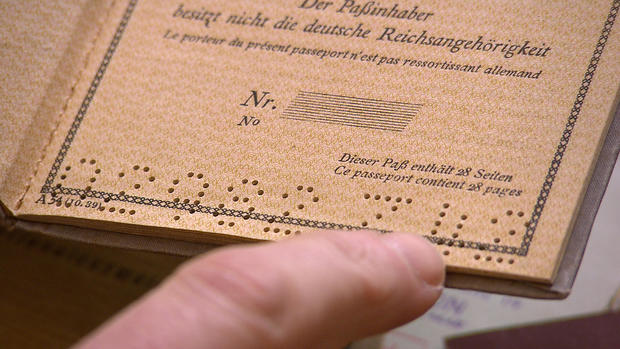

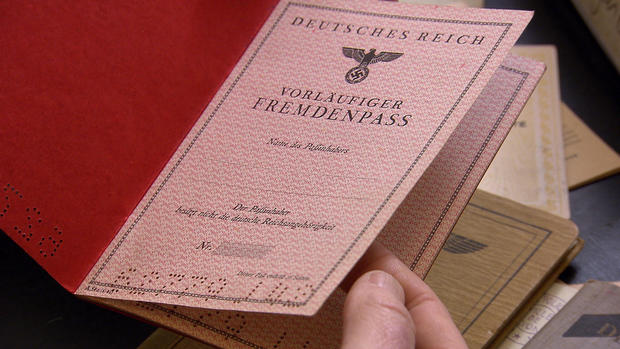

Kaminsky knew the chemical that could do the trick: lactic acid. He was recruited to join the resistance, using his skills to alter original documents and forge new ones — identity cards, passports, food ration cards, birth certificates, marriage certificates.

As Anderson Cooper reports this week on 60 Minutes, he and the resistance networks he worked with helped save the lives of as many as 14,000 Jewish men, women, and children.

"You know, it's so rare to find a story like this," says 60 Minutes producer Katherine Davis in the video above. "It's on par with Schindler's List."

But unlike Oskar Schindler, Kaminsky was Jewish himself. At just 18, he initially met with the resistance to get new documents of his own. His family had Argentinian citizenship, and while Argentina was neutral in the war at the time, Kaminsky's father decided the family should adopt false identities for their safety. Kaminsky was sent to pick up their new papers at a fateful meeting in front of The Sorbonne.

On the broadcast, Cooper asks Kaminsky if he was frightened to join the resistance.

"Afraid of what?" Kaminsky replies. "Afraid of what? The risk was the same if you did nothing, so at least working in the resistance, I could fight. I was fighting for humanity."

So he fought with the sewing machines he used to create perforations in stamps. He fought by forging signatures and reproducing watermarks. His secret lab would become one of the biggest suppliers of forged documents for French Jews, producing, he says, as many as 500 a week.

In the video above, Kaminsky shows Cooper some of the documents he created and compares them with the originals he modeled them after.

"When it's perfect, it's impossible to distinguish," he says. "If you can recognize the difference, then it's poor work."

Kaminsky and his daughter, Sarah, now tell his story to high school students around France. And as she explains to Cooper, her father's forgery didn't end with World War II — it lasted almost another 30 years.

Shortly after Paris was liberated, Kaminsky was recruited by the French Secret Service to produce documents for French spies who were being parachuted behind enemy lines. After the war ended, he began forging documents for many other people fleeing dictatorships in places like Portugal, Greece, Spain, and Venezuela.

"His daughter really describes him as somebody who can't stand to see injustice," Davis says. "I think that did drive him. He certainly wasn't driven by money, because, as he says, he never took any money for any of his work."

For Kaminsky, forging documents was a cause.

"Yes," Sarah Kaminsky agrees. "And it had to be for free."

The video above was produced and edited by Lisa Orlando.