The flags of their fathers

President Obama's visit to Hiroshima this past Friday is one indication of how the legacy of the war with Japan has come full circle. The growing number of wartime flags returning home is another. Here's Lee Cowan:

Opposing sides in war share little, other than perhaps a battlefield, and the longing to go home.

Glenn Stockdale of Billings, Montana, DID come home. He fought the Japanese in the Pacific until 1945. As a young staff sergeant, he saw things most of us can't even imagine, and until the day he died, at age 84, kept most of it to himself.

"Never talked about the war," said his son, Terry.

What he knew of his dad's service came mostly from rummaging through his father's old footlocker: "It was in the basement, so as kids you go down and look at it, see what's in here, what's in there."

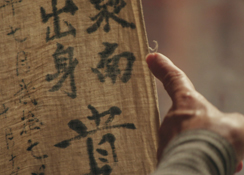

Among other things, Terry found a Japanese flag, carefully folded, stained with blood, and covered in writing.

Then he found another, and another.

"They were memories of the war. A trophy -- spoils of war," Terry said.

Collecting them was commonplace; pictures abound of U.S. servicemen posing with the flags.

Known as a Yosegaki Hinamaru, Japanese soldiers carried them as keepsakes into battle -- good luck charms, of sorts -- with wishes from family and friends scrawled around the Rising Sun. Keepsakes in battle.

But in Glenn Stockdale's footlocker, the flags had become just ghosts of a long-ago enemy -- and nearing the end of his father's life, Terry suggested it was time the flags go home. "I thought it'd be nice to send it back to Japan. He said no."

Because? "It must be the hate from fighting people and just war. I don't know what that does to individuals. I've never been there."

So that's where things, and the flags, sat for more than a decade, until Terry heard another WWII vet speak of the flags.

His name was Leland "Bud" Lewis. Lewis was in the same Infantry Division as Terry's father, the 41st. They never met. Lewis was behind the front line, sending the bombs and the bullets up, something that at age 95 he still doesn't take lightly.

"I provided all the ammunition that killed all these folks," he told Cowan. "And I'm not exactly totally happy that I did that, but at the time that was my job. I couldn't question that."

"Why now? Why is it important you think to return the flags now?"

"Well, it's a closure," Lewis replied. "You can't keep hating people."

Inspired, Terry Stockdale packed up one of his father's flags and mailed it to the only place he thought could help: a home in Astoria Oregon, a small town along the Columbia River, where the flags are celebrated with a ceremony.

"This is not the flag; it is the spirit of the soldier," said Keiko, who with her husband, Rex Ziak, run a non-profit called the Obon Society. "We are wishing he can find a way to find his family in Japan."

In Japan Obon is a festival honoring the spirits of ancestors. "When we started out, we thought we were just helping Japanese families receive heirlooms," said Rex. "Then, as this progressed, we realized that we were connecting these families and providing closure and healing on both sides."

Keiko's grandfather died fighting in the Pacific, but his grave is empty; his remains never came back. But one day his flag did. "We all thought that the spirit of the grandfather finally wanted to come home to see us," she said.

It had such a profound effect they wanted to see if they could identify more soldiers' flags and send them back to Japan, and have turned their attic into a makeshift war flag research center.

Once word got out, they were stunned. Flags from veterans, or their families, started arriving almost weekly.

"Sometimes they include photographs of their father as a soldier, or family pictures of themselves now," Rex said. "It is this connection of this family to this family that were brought together through war."

So far they've reunited about 60 flags with Japanese families, and have more than a hundred they're researching -- all at their own expense.

"You guys have essentially spent your life's savings to do this," said Cowan.

"It's just a very important thing to do," Keiko replied.

Terry Stockdale waited, and hoped, and then came word that the Obon Society traced his flag back to a man named Yoshigusu Kishi, a young soldier who kissed his wife, his seven-month-old son and his two-year-old-daughter goodbye -- and never saw them again.

Those children -- Masaru Kishi (now 73) and his sister, Kayoko (75), both live outside Osaka. They knew little of their father, until one day last December, when the phone rang.

"When I got the call, I thought, this was impossible! My mind just went blank," Masaru said. "After 70 years, I never dreamed something of my father's would surface."

They found out Stockdale not only had their father's flag, but he wanted to come to Japan to deliver it himself.

Anxious, the Kishis had an emotional meeting with Stockdale at the train station.

"I mean, yeah, it's just beyond comprehension what it meant to them," Stockdale said. "You know, it wasn't just a souvenir; it was their father coming home."

He officially handed it over at a formal ceremony, and then stepped back to watch two people who never knew their father unfurl his flag together.

"We don't know the warmth of his hands, the sound of his voice," said Kayoko. "I can't remember a thing about my father. And I said, 'I'm sorry, Dad,' to that flag. 'I'm so sorry.'"

Now, where Mr. Kishi prays, sits a framed photo of Terry -- a captured moment a generation in the making.

"You know the old saying, it's better to give than to receive? Definitely, you know?" said an emotional Stockdale "It just feels so good to do something for somebody."

As for his own father, Stockdale hopes that Staff Sergeant Glenn Stockdale is also finally at peace.

"He'd be proud of me," Terry said. "He would know it's the right thing to do."

For more info:

- Obon Society, Astoria, Ore.

- Obon Society gallery of Yosegaki Hinomaru (flags)

- Columbia River Maritime Museum, Astoria, Ore.