When opioids impact the whole family

Ann Sinsheimer's meditation cushion doesn't get much use these days. It's crammed under a desk. Instead, in the extra room where she used to begin her mornings with a clear mind and focused breathing, a heart-eyed emoji pillow sits on the bottom level of a bunk bed, under the watchful eye of a Shawn Mendes poster.

After all, there's not much space — or time — for contemplation with two young girls in the house: Sinsheimer, 55, and her husband Marvin Sirbu, 72, are now raising two granddaughters because his daughter has an opioid addiction.

"What was a big, kind of empty house is now just packed," Ms. Sinsheimer said recently, her warm voice lacking any expected exasperation. "And we had to get more silverware because we didn't have enough to accommodate everyone."

The couple is part of an increasing population of older Americans stepping in to raise grandchildren who have been removed from their parents' care, largely because of addiction to drugs, and increasingly, opioids. From oxycodone pills to heroin and fentanyl, opioid addiction has impacted families nationwide, even reaching this quaint, tree-lined street in the Oakland neighborhood of Pittsburgh.

In May, 60 Minutes correspondent Bill Whitaker reported on the story, speaking with families near Salt Lake City, Utah, where children were getting a chance at a normal life after being raised in the wreckage of the opioid crisis.

Generations United, a Washington D.C.-based organization, has watched grandparents step in as guardians during the crack and meth epidemics of years past. But this time, the organization's executive director Donna Butts said, feels different.

"With the opioid epidemic, it seems so much more severe and, in some ways, more hopeless," she said. "Which is why I think the grandparents and other relatives that are stepping forward are playing such a critical role because the hope is with the children."

Marvin Sirbu's hope, at least initially, was that his new role as guardian would be temporary. When he first took emergency custody of his granddaughters, he and his wife assumed the girls would live with them while his daughter went to rehab, maybe for a few months.

That was two and a half years ago.

Today, Brooklyn, 9, and Skylar, 7, are adjusting to their new lives — or at least, attempting to. Fiercely loyal to her mother, Brooklyn distrusts other caregivers and often throws raging tantrums. Skylar's distress used to manifest physically through involuntary twitches and night terrors. Now she freezes when people around her raise their voice.

"She can't even handle when we're disagreeing about where to go for dinner," Ms. Sinsheimer said.

The impact of childhood trauma

Any parent knows the cost of raising children — the food, the child care, the shoes outgrown in a season — but older adults are often doing it on a fixed income. According to Generations United, more than one-fifth of the estimated 2.6 million grandparents caring for grandchildren are living in poverty. Forty percent are over the age of 60, and a quarter have a disability. To make ends meet, grandparents often borrow from their retirement savings, stay in the workforce longer, or return to work altogether.

Grandparents who take in grandchildren through the foster care system receive a stipend, which varies by state, along with services such as a caseworker. But the vast majority have taken custody without government involvement. According to Ms. Butts, for every child that's in the formal foster care system, there are another 18 to 20 outside it.

In addition to the everyday costs of raising children, these grandparents also have to pay for court costs and legal fees as they untangle the web of the child welfare system.

And then there's the trauma that opioids cause.

Mr. Sirbu said while his daughter was addicted, she wasn't working; her boyfriend, Skylar's father, supported her and both girls as an apprentice for an electricians' union. The couple got into raging fights — screaming back and forth, throwing possessions out on the curb, calling the police on each other — with Brooklyn and Skylar nearby, watching and often hungry because there was no food in the house. When Skylar's father moved out, Mr. Sirbu said, "all stability disappeared."

"The grandchildren have been exposed to trauma. The grandparents have often been exposed to trauma," Ms. Butts said. "What they really need is to understand the impact of trauma on the children and try to help support them as they deal with that. Also, they need to have access to trauma-informed services, the services that can really help them to overcome what they've experienced."

In March, 60 Minutes contributor Oprah Winfrey reported on trauma-informed care. The approach focuses on a person's experience before trying to correct their behavior, such as poor performance in school or out-of-control anger. Winfrey spoke with Dr. Bruce Perry, a leading expert on treating childhood trauma, who said that the ability to overcome a troubled childhood comes down to something simple: relationships. Children who have someone who values them fare better in the long run.

In other words, grandparents provide more to their grandchildren than the food on their plates and the emoji pillows on their bunk beds.

"We do know from work and studies that have been done on trauma that grandparents really can and do play a protected role," Ms. Butts said. "And because of that, they offer the children a sense of familiarity and stability."

Finding resources

In Maine, the number of children being raised solely by their grandparents has increased 24 percent over a five-year period — a number that caught the attention of Senate Aging Committee Chair Susan Collins, R-Maine.

"It was clearly due to the opioid crisis because the parents were in treatment and unable to care for their children, or they were in prison, or they were nowhere to be seen in some cases," Ms. Collins said. "That had me interested in the issue."

Trying to help grandparents who find themselves in this situation, Ms. Collins last May co-sponsored a bill with Sen. Bob Casey, D-Pennsylvania, the ranking member on the Aging Committee. Dubbed the Supporting Grandparents Raising Grandchildren Act, the legislation passed the Senate in March by unanimous consent. It awaits a House vote.

"You can imagine the strain this puts on someone who hasn't had a young child in the house for decades." – Sen. Susan Collins

According to Ms. Collins, the bill would create a federal task force that would identify, coordinate, and disseminate information and resources to help grandparents meet the needs of the children in their care. She emphasized that the goal is not to set up a new federal program, but rather to create a temporary group that consists of grandparents and representatives from key agencies. Additionally, she said the task force could make recommendations to states, which set their own laws regarding compensation for foster caregivers.

It would also focus on helping the grandparents maintain their own health and emotional well-being.

"You can imagine the strain this puts on someone who hasn't had a young child in the house for decades," Ms. Collins said.

Marvin Sirbu doesn't have to imagine. Awake early in the morning to get the girls to school, he's losing sleep and worrying about his health, especially because he said he's now older than both his parents were when they died.

He and Ms. Sinsheimer say the Senate legislation could help other grandparents, especially when they first become the primary caregivers. Older adults haven't raised children for a long time, so they don't know how to access support, legal aid, and social services. They also have questions: Can grandparents claim their grandchildren as dependents when filing taxes? Are they eligible for extra Social Security funds as senior caregivers to young children?

In the meantime, organizations like AARP and Generations United have compiled state-by-state resources for grandparents thrust into an unexpected role as parents.

"I have my kids back"

On a warm spring day this May, a young woman walked into Dr. Frank Kunkel's office in western Pennsylvania and threw her arms around his neck.

"I have my kids back," she told him.

A former opioid addict, she sought treatment from Dr. Kunkel, the president and chief medical officer of Accessible Recovery Services (ARS). Her treatment — a diligent combination of Suboxone and cognitive behavioral therapy — stabilized her enough to reclaim custody of her children.

"We see a lot of that," Dr. Kunkel said. "We see a lot of people that spin out of control. They're involved with the judicial system and all that. And we see grandma have the kids for a while. Then they'll get back on track with things legally, and they'll get on our medications, and they'll get in seeing their therapist, and they'll turn their life around. We see that every day."

"The prejudice against these patients is dramatic." – Dr. Frank Kunkel

That doesn't mean the road to stabilization — Dr. Kunkel is loath to say patients ever fully recover — is easy. Opioid addiction maintains a powerful hold on a user, he warns, and those in recovery should stay on drugs like buprenorphine (which is marketed under the brand names Subutex and Suboxone) for as long as they need.

"The literature is very clear on this. If you push people off of these medicines, you can kill them," he said. "For us, success is stabilization and no longer using illegal, illicit drugs, getting their family situations back."

Dr. Kunkel, a stout man with silver-white hair, sounds almost evangelical in his desire to help opioid addicts. An associate professor of anesthesiology at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, he understands the nuances of managing chronic pain. In his spare time, he makes daily visits to any number of the 31 ARS offices he has opened throughout Pennsylvania, offices that see upwards of 200 new patients weekly. At night, he assembles Narcan rescue kits in his basement, where he fills blue plastic pencil cases he buys himself.

Dr. Kunkel is frustrated by people who view opioid addiction as a "disease of ill-repute," a bad habit perpetuated by weak people. He said he's had to open some of his ARS offices in basements of shabby buildings because people are reluctant to rent him other space.

"The prejudice against these patients is dramatic," he said.

Following "right down her mother's footsteps"

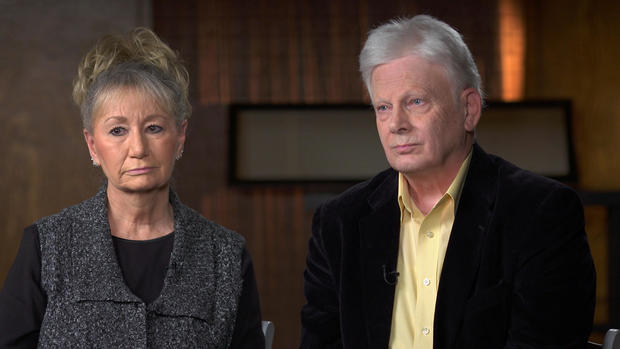

Terry and Jean Childs were looking forward to retirement. They were going to travel and fix up their home in Salt Lake City, Utah. But when their daughter, Katie, died from a heroin overdose, their plans changed. They became the primary caregivers to their two granddaughters, Jaycee, 16, and Trella, 14.

Having already buried their daughter, the Childses are now afraid of addiction repeating itself in their 16-year-old granddaughter.

"She has a hard time in life," said Jean Childs, 66. "And she's very much like her mother."

One night, her grandfather found Jaycee in bed, unresponsive and lacking a pulse after she drank a Gatorade bottle full of vodka that a friend had brought over. Paramedics took her to the hospital, where she lay unconscious for six hours.

But the Childses say the incident didn't faze her. Jaycee is currently in temporary, court-ordered state custody.

"In some ways, we think she's following right down her mother's footsteps and so afraid that she's going to wind up the same way," said Terry Childs, 71. "And we're doing everything we can to try to prevent that."

The couple has reason to worry. According to the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence, family history is the most reliable indicator for risk of drug dependence. Dr. Kunkel said it's not just seeing addictive behavior in a parent; it's also a factor of nature. "It's very, very strongly genetically tied," he said.

The Childses find support in Grandfamilies at Children's Service Society of Utah, a program that helps local grandparents and grandchildren adjust to new family arrangements. They say it helps them feel like they're not going through this situation alone. Facebook also provides a sense of solidarity, hosting support groups like Grandparent 2 Grandparent, which give parents of addicts and grandparents like the Childses a place to share advice and swap stories.

Or sometimes, just to vent.

Previously retired, Jean has had to return to substitute teaching to help with the family's finances — the house payment, the car payment, the pairs of Levi's the girls want. The couple no longer goes to the movies or eats out at restaurants. Last year, one of Terry's best friends called with a tempting offer, telling him, "Some of us are getting together. We're going to Yellowstone Park for a few days."

But Terry couldn't go. He had to attend a parent-teacher conference.

To watch Bill Whitaker's 60 Minutes report on grandparents raising their grandchildren because of opioid addiction, click here.