The dangers of efficient frontier models

(MoneyWatch) NASCAR race cars are sophisticated, complex automobiles. In the hands of, say, Tony Stewart, they're capable of great feats. In the hands of a drunk driver, the same vehicle can be deadly.

The financial equivalent of racing cars is an efficient frontier model. They're one of the most touted, yet most misunderstood and misused, tools in the field of financial planning.

Economist Harry Markowitz first coined the term "efficient frontier" almost 50 years ago. He used the term to describe a portfolio that was most likely to deliver the greatest return for a given level of risk. Today, there are many efficient frontier programs available. They begin by having an individual investor answer questions about their risk profile. The program will then generate a portfolio consisting of various asset classes that will deliver the greatest expected return given the individual's risk tolerance. Sounds like a wonderful idea.

So what's the problem? Only this: Understanding the nature of an efficient frontier model and the assumptions on which it relies. As with a sophisticated racing car, a powerful tool in the wrong hands can be a very dangerous thing.

Efficient frontier models effectively try to turn investing into a science, which it isn't. For example, it's logical to believe that stocks will outperform bonds in the future. The reason is that stocks are riskier than risk-free Treasury bills. Investors will demand an "equity risk premium" to compensate them for this risk.

While the past may be a guide to the size of the equity risk premium, it's no guarantee. For example, if we look at the period 1926-1990, the equity risk premium (using the Fama/French Total US Market Research Factor) was 7.9 percent. Once we include the bull market of the 1990s, the risk premium jumps to about 8.8 percent. As you can see, the equity risk premium isn't constant. We shall see why this even seemingly small change is very important when it comes to efficient frontier models.

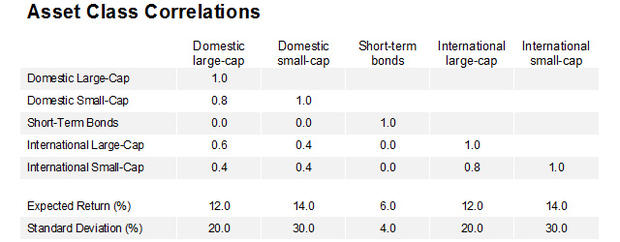

Efficient frontier models rely on historical data and relationships to generate the "perfect" portfolio. Expected returns, correlations, and standard deviations (measure of volatility) must be provided for each asset class, or building block, that could be used in a portfolio. Let us begin with a simple portfolio that can potentially invest in just five asset classes:

- Domestic large-cap

- Domestic small-cap

- Short-term bonds

- International large-cap

- International small-cap

The table below has our assumptions regarding historical data for returns, correlations, and standard deviations. Let us also assume that we have designated a 12 percent standard deviation of the portfolio as our desired level of risk. An efficient frontier model will then generate the "correct" asset allocations.

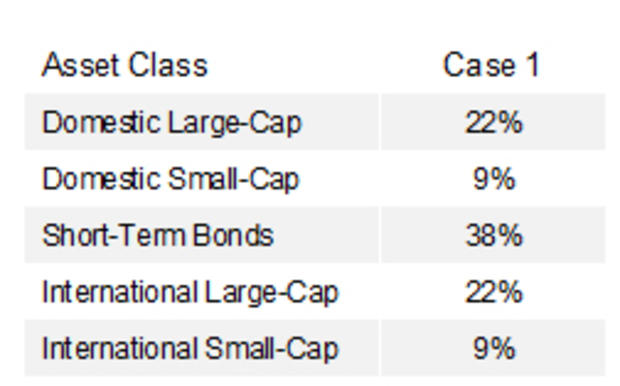

The following is the output of our efficient frontier model.

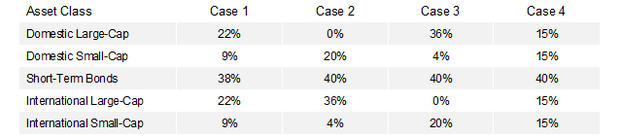

We will now make a series of minor changes to expected returns, standard deviations, and correlations to see how sensitive the efficient frontier models are to assumptions:

- In Case 2, we reduced the expected return of the domestic large-cap asset class from 12 percent to 11 percent

- In Case 3, we increased the standard deviation of the international small-cap asset class from 20 percent to 22 percent

- In Case 4, we reduced the correlation between domestic small-caps and international small-caps from 0.4 to 0.2

In each case, the efficient frontier model generated a dramatically different asset allocation, entirely eliminating an asset class from the portfolio in some cases. This implies a precision that just doesn't exist in the field of financial economics.

Investing isn't a science. It's foolish to pretend that we know in advance the exact levels for returns, correlations, and standard deviations. Yet that's the underlying assumption of any efficient frontier model. Experienced practitioners know that to come up with something intelligent, they must generally impose constraints on efficient frontier models. Examples of constraints might be that no asset class either exceed 30 percent or be less than 10 percent of a portfolio. Another constraint might be that total international assets not exceed 30 percent or 40 percent of the portfolio.

The impact of applying such constraints is similar to what a simple, common-sense approach without modeling would end up with -- a relatively balanced globally diversified portfolio with exposure to all the major asset classes. In other words, don't waste your time with efficient frontier models.

In my experience, many investors who use efficient frontier models are unaware of their pitfalls. These models are being marketed as solutions to the problem of portfolio construction, but they come without instructions. The models are marketed to individuals not only over the Internet, but also by many large companies to their 401(k) and profit-sharing participants. These corporations may view this offering as a way to fulfill their fiduciary responsibility to educate their plan participants. That's a real problem given the model's pitfalls (unless of course they come with the appropriate instructions and disclaimers).

Given the problems with efficient frontier models, perhaps investors should be required to show their "driver's license" before being able to use such a model.

Image courtesy of Flickr user pocketwiley