The brilliant, unique world of child prodigies

Watching him play badminton with his dad, you'd probably figure Suborno Bari for your typical 12-year-old kid. You'd be very wrong. Mathematics is his passion. "Yeah, most of the time I'm having the most fun when I'm doing math and physics," he said.

Indecipherable homework assignments that would mystify mere mortals are, well, child's play to Suborno, something his parents marveled at early on. "He fell in love with math," said his father, Rashidul Bari, also a mathematician. He said that by the age of four, his son was stumping him with math problems. "He read all the books that I had," he said. "And he was challenging me from the book, that I wasn't able to give him a satisfactory answer."

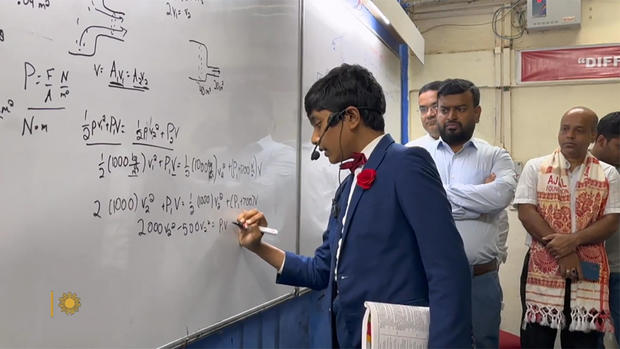

So, it's no surprise today to find Suborno delivering university lectures in India, something he started doing at age seven. That's right: seven!

Since then, Suborno has skipped multiple grades, scored a 1500 on his SAT, and at the ripe old age of 12, started college this past September at New York University. "It feels like just the next natural step," he said. "Most kids go to college after high school, so I said, 'Why not me?'"

Despite his progression, Suborno seems to have a pretty balanced point of view. "I know it sounds strange, because it sounds like you're talking to some business CEO on '60 Minutes,' that's, like, 35 years old," he laughed. "But instead I'm only 12. It feels like the voice isn't matching up with the person right in front of you."

I asked, "Do you sometimes wonder at the fact that you're only 12?"

"Not really," Suborno replied. "I've seen my birth certificate."

Psychologist Ellen Winner, a professor emerita at Boston College, and a leading authority on child prodigies, said Suborno demonstrates the hallmarks of a child prodigy. She says virtually all exhibit something she calls a "rage to master."

"This is all the child wants to do all the time," Winner said. "Not even wanting to go out and play. The kid wants to stay inside and work on whatever it is that that child is gifted in. These are kids that really live in their own minds."

"Is this fairly obvious when you talk to these kids?"

"Yes, it is very, very clear, especially in certain domains – in music performance, in mathematics, in drawing realistically," Winner said.

But there is one area where she thinks prodigies are overlooked, because they excel at something a lot murkier: Abstract art. "It's much harder to detect, because the work doesn't look totally different from typical kids," Winner said. "But it doesn't look totally the same, either. It's more complex, it's more structured."

So, while we've all marveled at the obvious skills of math prodigies like Suborno Bari, music prodigies, or chess prodigies, what about young artists who seem to be following in the footsteps of, say, Jackson Pollock?

Meet four-year-old August Gardener, Professor Winner's grandson, who has been obsessed with abstract art for most of his young life. He's done hundreds of paintings, drawings, sculptures, and mixed media artworks.

Asked how what he's doing compares to the scribbling of the average four-year-old, August's father, Andrew Gardener, a former schoolteacher, replied, "It's the drive. It's the desire to continue doing it, and keep working, and the top-of-mindness of it."

August's mother, Vanessa Gardener, said, "He's often incredibly deliberate for a four-year-old boy who, like, when he's not doing that, you know, he runs around like a maniac, like a lot of four-year-old boys. But when he's working on his art, everything is very thought out and, you know, particular."

That deliberate process is the hallmark of an abstract art prodigy, says Jen Drake, a psychology professor at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York. Drake (who's worked with Winner in the past) is now conducting a major study of art prodigies, and August is part of it.

Speaking of August, Drake said, "I'm really struck by his focus. That one drawing he spent several days working on, that is definitely a 'rage to master,' [demonstrating] their willingness to go back to the drawing to add something to it."

But what of the end result? Is that art? "That's a really good question," said Drake. "And I think because his work is abstract, it may be difficult to assess the skill in there. But there is a use of color and line and form that's not found in typical preschoolers."

And no matter what you think of August's art, Drake says his focus in making it is what really sets him apart.

"Are we talking prodigy?" I asked.

"I would say yes. Definitely," Drake replied.

And August is in good company: Pablo Picasso was a child prodigy. In fact, from Mozart to Einstein to Stevie Wonder, the list of brilliant people who started young is long. But being a prodigy doesn't guarantee future greatness. According to Ellen Winner, "Most prodigies do not go on to be major adult creators in their area of giftedness. The reason is that being a child prodigy means you are mastering something that's already been invented. And to be a major adult creator, you have to go beyond what's already been done, and develop something really new."

So, how often do we get a Picasso or a Mozart? "Very, very rare," Winner said.

But don't tell that to August just yet … and certainly not to math whiz Suborno Bari. He's got his eye on a Ph.D. by 16. And then what? "I mean, I don't want to just be, like, a superstar for five years and then completely vanish and have videos made on me 10 years later saying, 'What happened to Suborno Bari?' I want to actually leave a mark that people will remember me for."

For more info:

- Psychologist Ellen Winner, professor emerita, Boston College

- Jennifer Drake, associate professor, Brooklyn College/City University of New York

Story produced by Amiel Weisfogel. Editor: George Pozderec.