The banking crisis 10 years on, and the danger of another crash

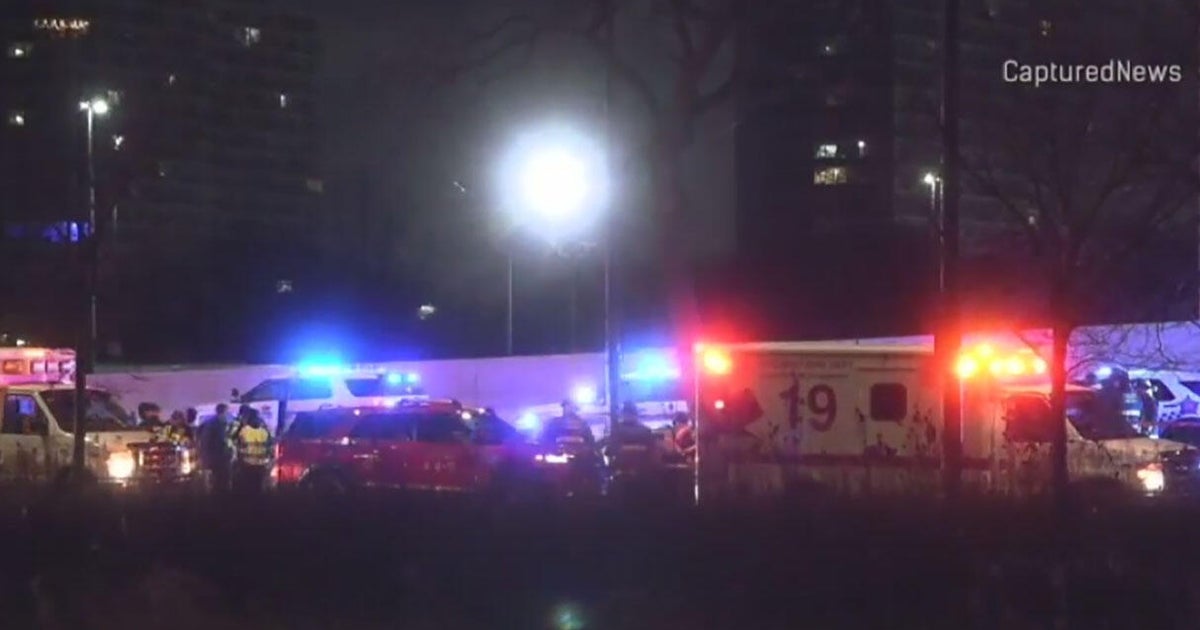

Gretchen Morgenson was a business columnist for The New York Times during those dark and frightening autumn days of 2008, when Lehman Brothers was down brought by bad mortgage investments, and was liquidated; 25,000 employees lost their jobs. Fearing it would be next, Merrill Lynch agreed to a shotgun marriage with Bank of America. Meanwhile, two of the country's largest mortgage lenders, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, required a government bailout.

"It was very scary," Morgenson said. "Why are these companies failing? Who was next?"

The banking system was near collapse, the stock market in free fall. And to many, it seemed like government officials were as clueless as the rest of us

"There was just a real sense of being in a dark room filled with furniture that you were gonna stumble on and fall over and that you didn't know how to kind of maneuver in," Morgenson said. "There were so much that we didn't know, and that, really, people did not want us to know.

Morgenson says that the seeds of the crash were sewn in the boom-years leading up to it. Home prices were skyrocketing, and many believed they would never fall.

One homeowner, a Mr. Sabrowski, told the "CBS Evening News" in May 2005, "We're pretty confident that the housing market here is not going to go down at all; it's just going to go up!"

To keep their monthly payments low, more and more borrowers were opting for risky mortgages. Broker Michael Brown told CBS News that year that roughly three-quarters of his business involved adjustable-rate mortgages: "And out of those adjustable rate mortgages, I'd say 95 percent are interest-only."

And many lenders were stretching the limits, offering so-called "subprime mortgages" to those with shaky credit, allowing them to buy homes they could barely afford.

Morgenson said, "There was, underlying this drive for home ownership in the United States, almost an overarching policy that bigger rates of home ownership was good for America."

Few knew that at the same time some banks were pushing those untraditional mortgages, in order to repackage and sell them to global investors, said CBS News business analyst Jill Schlesinger. Pension funds, insurance companies, even other banks bought these mortgage-backed securities.

It was, said Columbia University professor Adam Tooze, a trigger. "That's what sets the bomb off," he said.

Tooze has focused his historian's eye for a new take on the causes and effects of the financial crisis, in his book, "Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World" (Viking). He says policymakers were caught by surprise at just how fast the crisis spread.

"I don't think they understood the way in which a relatively small bit of the mortgage market, which is what sub-prime was, how that could spiral into this general crisis of the Atlantic banking system," Tooze said.

- How Merrill Lynch Bribed traders to buy bum mortgage-backed securities (CBS Moneywatch, 12/23/10)

As home prices plunged, millions of homeowners could not repay the money they borrowed, driving down the value of those mortgage-backed securities.

And the banks didn't have the money that they were using to hold those mortgage securities with. "Because they'd borrowed it," Tooze said.

The result: taxpayers had to shell out billions to help cover the banks' losses.

Schlesinger asked, "What do you think would've happened if the mantra of, 'Let them fail,' were enacted?"

"I think we would've seen a catastrophe of the type we've not seen before, worse even than the Great Depression of the 1930s," Tooze said.

But those actions sparked fierce public anger, leaving little appetite for saving what some believed were reckless homebuyers. Rick Santelli, on CNBC, "How many people want to pay for your neighbor's mortgage that has an extra bathroom and can't pay their bills?"

Swift action may have saved the financial system, but not before $19 trillion in household wealth evaporated, along with nearly nine million jobs.

Schlesinger asked, "In retrospect, a lot of people feel like the banks were bailed out – 'Okay, I understand that, save the system' – but people were left hanging out to dry. Is there something to that?"

"Absolutely," Tooze said. "There's a huge imbalance between the emergency efforts that kept the system going, and the very slow-moving and inadequate measures that were enacted later on to support American homeowners.

"They were very slow-acting. They provided relief to a small minority of American homeowners, many years after the acute crisis of 2008. And in the meantime, ten million American families lost their homes."

All of which, Tooze says, made the recovery long, painful, and uneven for ordinary American families. "That's where the real loss is," he said.

So what about now? Despite recent turbulence, ten years later the stock market is still at an all-time high, and the unemployment rate is the lowest in nearly fifty years, but many of the new rules put in place after the crisis to protect the system from another meltdown are now being weakened.

- Trump signs bill signing scaling back Dodd-Frank (CBS News, 05/24/18)

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau enforcement actions halt under Mulvaney (CBS News, 04/10/18)

The danger of that, Tooze said, "is that you have banks which are not able to take the hit of a large amount of unexpected losses, and are not able to withstand a sudden panic and loss of confidence when people just want to pull their money out of the banking system."

Gretchen Morgenson said, "The banks are much more well-capitalized [today]. They have a lot more money set aside for a rainy day than they did leading up to the crisis. But by not prosecuting any very high-level executives who were involved, I think that message was very clear that this kind of behavior, this kind of big risk-taking behavior that risks the entire financial system, will not be punished."

Morgenson, now an investigative reporter at the Wall Street Journal, worries that failure to hold anyone accountable will resonate for years to come.

"I think people get what happened, that this inequality that was pervasive in the response to the crisis, the very powerful institutions got taken care of. The individuals who were powerless did not. I think people understand that very well," she said.

- Investors may be forgetting the lessons from Lehman Brothers collapse (CBS Moneywatch, 09/15/18)

- Lessons for next U.S. financial crisis from 3 key ex-officials (CBS Moneywatch, 07/18/18)

For more info:

- Jill on Money

- Follow @JillonMoney on Twitter

- "Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World" by Adam Tooze (Viking), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon

- Adam Tooze, Columbia University

- Gretchen Morgenson, The Wall Street Journal

- Follow @gmorgenson on Twitter

Story produced by Mark Hudspeth.