Teachers' wage penalty is at a record high

Educators may not go into teaching expecting to get rich, but it's a job that historically has supported a middle-class lifestyle.

That may be harder to achieve today, thanks to years of eroding pay for teachers, according to a new study from the Economic Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank. Teachers now earn 11.1 percent less than comparable professionals, representing a record pay gap between educators and other college-educated workers, according to the study.

The shift represents an about-face from the 1960s, when teachers enjoyed a pay advantage of almost 15 percent. Half a century ago, that pay advantage attracted talented workers to education -- especially women, who at the time didn't have as many career opportunities as they do today. As teacher pay has eroded, students are increasingly snubbing education for more lucrative fields.

"I don't think anyone expects that teachers need to be paid substantially above what other college grads earn, but when they are paid substantially less, it's harder to recruit teachers," said Larry Mishel, a co-author on the report and a distinguished fellow at the EPI.

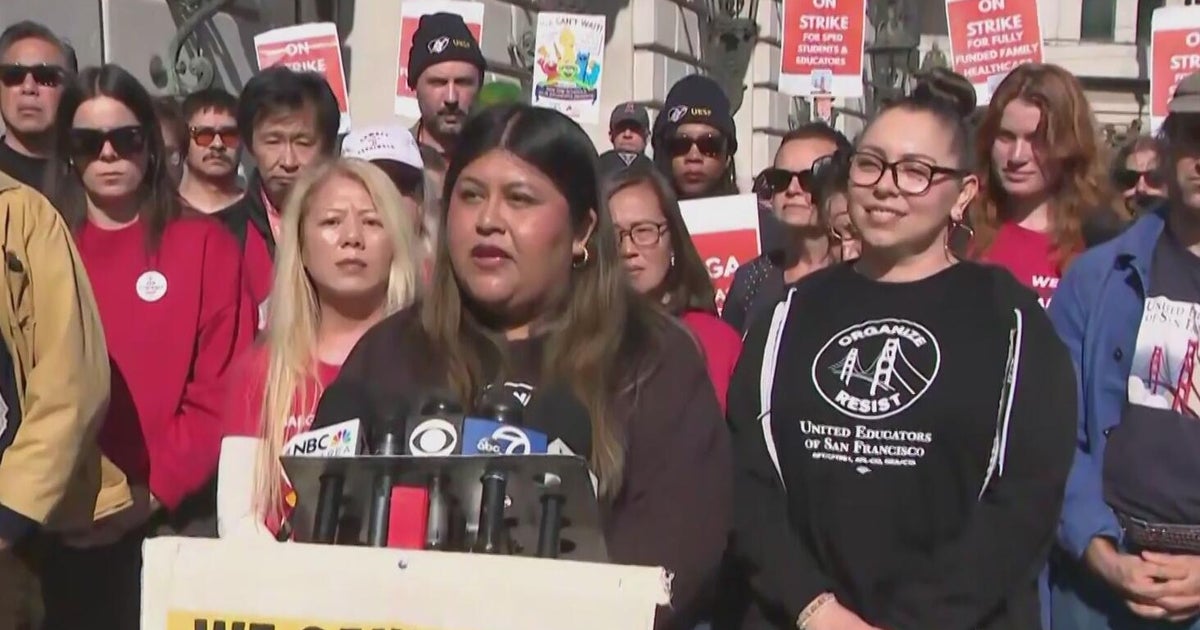

Teachers are earning almost 2 percent less than they did in 1999 and 5 percent less than their 2009 pay, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Teacher pay drew national attention earlier this year when educators in states such as Kentucky and Oklahoma protested and went on strike because of low wages and pension changes.

Comparing teacher pay with other professions helps explain why fewer students are opting to go into the field. The national average starting salary for a teacher is $38,617, according to the National Education Association. But the average salary for recent college grads overall is about $50,400 annually, consulting firm Korn Ferry found.

Schools are already feeling the impact. As students return to the classroom, many schools are reporting teacher shortages. To be sure, the problem isn't new -- it emerged in the wake of the Great Recession, when school districts cut staffing to deal with budget crunches. But it's snowballing, thanks to an increasing number of teachers leaving the field for jobs in other industries.

Even though the U.S. economy is improving, states aren't always replenishing school funding and teacher pay. Some states have slashed spending to pay for tax cuts for corporations and top-earning residents. The EPI study noted that 25 states now spending less on education than before the recession had also enacted tax cuts.

Four of the states with the biggest pay penalties for educators saw teacher protests during the last academic year, the study pointed out. Those are Arizona, with a 36.4 percent pay penalty; North Carolina (35.5 percent pay penalty); Oklahoma (35.4 percent); and Colorado (35.1 percent.) In no states do teachers earn more than other college-educated professionals, the EPI said.

The pay penalty would be even higher if it weren't for the positive impact of strong benefits. Compared with other professionals, teachers receive better benefits for health care and other nonwage compensation, the EPI said. Based on wages alone, the teacher pay gap would be 18.7 percent, the EPI said.

School districts may be making a trade-off by offering better benefits, yet failing to provide pay raises, Mishel said. Even so, that doesn't make it easier to swallow a growing wage gap between educators and other professionals, he said.

"You do need wages to pay rent and food and college tuition for your children," he noted. "You can't spend benefits."