"Running out of options": Syria's chemical weapons may be destroyed at sea

Syria's chemical weapons could be processed and destroyed out at sea, sources familiar with discussions at the international body in charge of eliminating the toxic arsenal told the New York Times and Reuters on Wednesday.

A U.S. defense official confirmed to CBS News correspondent David Martin that destruction of the vast stockpile at sea has always been an option, but four days after Albania rejected a U.S. request that it host a weapons decommissioning plant, it has become the leading option.

The official told Martin, however, that it was unlikely any at-sea option would be carried out by the U.S. Navy, suggesting a multinational force and a contractor could be brought in to do the work.

Western diplomats and an official of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons at The Hague told Reuters the OPCW was studying whether it might carry out the work at sea, on a ship or offshore rig.

Confirming the discussion, the OPCW official stressed there had been no decision: "The only thing known at this time is that this is technically feasible," the official said on Tuesday.

Speaking Wednesday to reporters at the organization's headquarters in the Hague, OPCW spokesman Christian Chartier said "technology is not the issue," explaining that a handful of countries, including the U.S. and Russia, already have the means to render a stockpile the size of Syria's useless, they just haven't tried it yet on the water.

Chartier said the only question was whether all the materials and the equipment required could be safely transported and used at sea.

"Experts say it is," he insisted.

Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, a U.K.-based expert in chemical and biological weapons, told CBSNews.com on Wednesday that while it is feasible, any destruction of the stockpile at sea would be "really challenging."

He said it should be considered only as a last resort, and he believes it's being considered now simply because the international community is "running out of options."

While other states, notably Japan, have dealt with chemical weapons at sea, mounting such a large and complex operation afloat would be unprecedented, independent experts said.

But given the equally daunting challenge of neutralizing over 1,000 tons of material in the middle of a civil war, and the reluctance of governments like Albania to defy popular protests against hosting any facility, it is being considered.

OPCW inspectors have checked Syria's declared 1,300 tons of sarin, mustard gas and other agents and the organization decided last week that most of the deadliest material should be shipped abroad by the end of the year and destroyed by mid-2014.

While battles for control of the highway from the capital to the Mediterranean port of Latakia have raised questions over the trucking of the chemicals to the coast, the Albanian refusal on Friday took negotiators by surprise, sources said, and prompted a radical shift in thinking to keep the plan on schedule.

Technically Feasible

Ralf Trapp, an independent chemical disarmament specialist, said of the offshore decommissioning suggestion: "It had to come up as an option at some point in time, given the circumstances.

He added: "Technically it can be done, and in fact at a small scale it has been done."

Japan destroyed hundreds of chemical bombs at an offshore facility several years ago. And Trapp said setting up a disposal plant on a floating platform might not differ greatly from the Pacific atoll where the United States destroyed much of its chemical arsenal through the 1990s.

Trapp said Syria's stockpile would require more complex treatment than the World War Two bombs that Japan found on the seabed, raised and destroyed off the port of Kanda from 2004-06.

The Japanese munitions, as a finished product, did not produce liquid waste, he said. By contrast, much of Syria's stockpile is of bulk "precursor" materials that were stored in order to manufacture weapons at a later stage. Burning these, or neutralizing them with other chemicals in a process known as hydrolysis, would produce large amounts of toxic fluids.

"If you use hydrolysis or incineration, there will be liquid waste," Trapp said. "So there will be problems with regard to environmental pollution that need to be addressed."

De Bretton-Gordon told CBSNews.com that given the huge challenges of trying to conduct the chemistry of hydrolysis, or the equally daunting task of burning more than 1,000 tons of highly toxic chemicals on any floating surface in unpredictable seas, any land-based option was a better one.

"Having this stuff bubbling around on a rough sea is very problematic," he said. "Imagine one of those (barges or platforms) pitched up and you turn 1,000 tons of chemical weapons into the sea?"

"These are really very toxic chemicals to get rid of," said de Bretton-Gordon, who has advocated publicly in U.K. media for Britain to volunteer to destroy the materials on its soil.

He suggested the, "EU, having shouted so loud for the removal and destruction of the weapons, and then sat on their hands... they have a bit of inward looking to do."

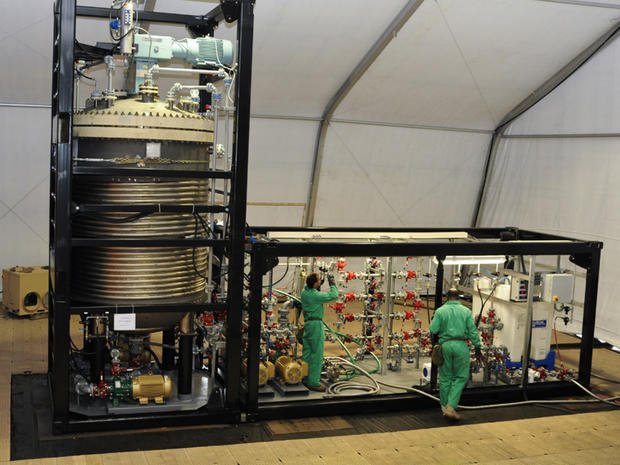

The huge system combines the chemicals with water and other chemicals and heats them to render them useless to a weapons program -- the process know as hydrolysis. De Bretton-Gordon said the process would yield a large amount of fluid waste (effluent) which would have to be either dumped or otherwise removed, but he said the effluent would have "virtually no toxicity."

He conceded, however, that "perception is everything," and said he would expect environmental groups to try and protest any sea discharge.

The sources who cited the FDHS system to the New York Times didn't confirm whether sea discharge of the effluent was part of the proposal.

The other option being weighed, according to the Times' report, would see five 2,700 degree incinerators placed on a barge to burn the chemical agents. That process would leave behind only salts and other solid waste.

De Bretton-Gordon said the U.S., Russia, France and other nations have incinerators made to burn chemical weapons, which he described as about the size of a small house.

Countries around the Mediterranean might not relish the prospect of such an operation, though shipping the Syrian material further afield could also pose difficulties.

Siting a facility close to shore could risk the kind of demonstrations in Tirana that forced Albania's government to change tack. Further out at sea could pose other problems, such as providing a rapid response to emergencies.

Trapp said that a "large floating platform at sea would not be fundamentally different" from the now dismantled U.S. chemical weapons destruction facility at Johnston Atoll in the North Pacific: "There are many technical and legal challenges," he said. "But it may be an alternative worthwhile considering."