Supreme Court tosses Wisconsin state legislative maps but keeps congressional maps in place

The U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday tossed out state legislative maps in Wisconsin that were drawn by Democratic Governor Tony Evers, but it left in place the governor's congressional maps.

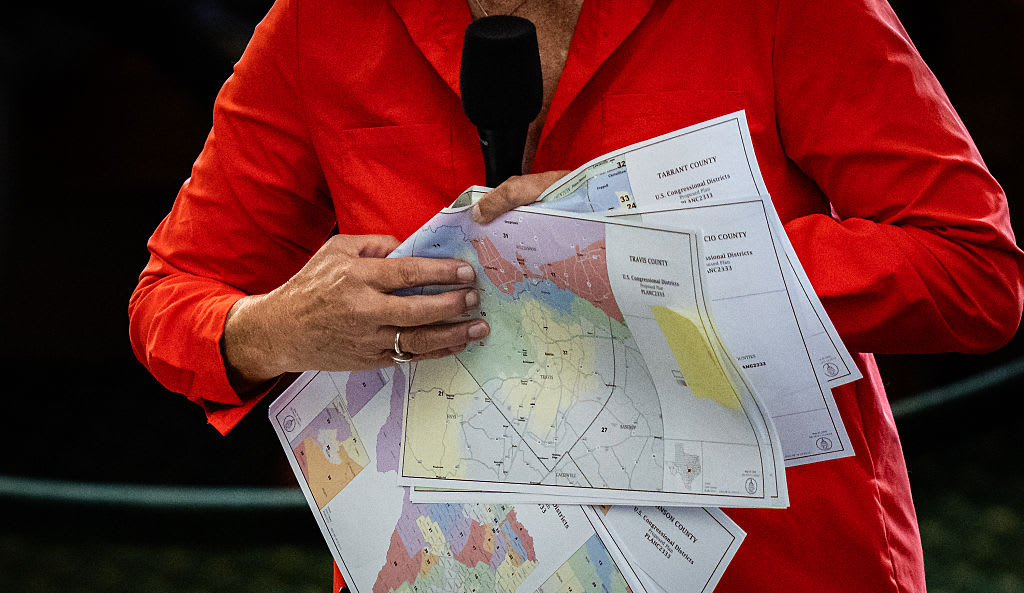

The Wisconsin Supreme Court earlier this month selected Evers' proposed legislative and congressional maps after hearing oral arguments from several groups that had also submitted maps. The case went to the courts after Evers and Republican state lawmakers couldn't agree on a set of maps and asked the Wisconsin Supreme Court to weigh in.

Evers' state legislative map created an extra majority-minority district, arguing that was necessary to comply with the Voting Rights Act (VRA). But Republicans argued that the state Supreme Court violated the Equal Protection Clause by selecting race-based maps without justification.

In its decision, the Supreme Court said that the Wisconsin Supreme Court is "free to take additional evidence if it prefers to reconsider the Governor's maps rather than choose from among the other submissions. Any new analysis, however, must comply with our equal protection jurisprudence."

The court said there is still "sufficient time" to adopt maps before Wisconsin's August 9 primary.

The Supreme Court said that Evers' "main explanation for drawing the seventh majority-black district was that there is now a sufficiently large and compact population of black residents to fill it." The unsigned per curiam decision said that reasoning embraced "just the sort of uncritical majority-minority district maximization that we have expressly rejected."

"[Evers] provided almost no other evidence or analysis supporting his claim that the VRA required the seven majority-black districts that he drew," the court's decision said.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court had told parties that it would select maps that made the "least change" to the current maps. Justice Brian Hagedorn, the court's conservative swing vote, said that Evers' "proposed senate and assembly maps produce less overall change than other submissions." Hagedorn also determined that Evers' proposals had satisfied the state and federal constitutions.

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justice Elana Kagan, called the Supreme Court's decision "not only extraordinary but also unnecessary."

"The Wisconsin Supreme Court rightly preserved the possibility that an appropriate plaintiff could bring an equal protection or (Voting Rights Act) challenge in the proper forum," Sotomayor wrote. "I would allow that process to unfold, rather than further complicating these proceedings with legal confusion through a summary reversal."

Democrats likely would have made some gains under Evers' proposal, but it was likely that Republicans would keep their majorities in the legislature.

Wisconsin's adopted congressional map will remain in place, since the U.S. Supreme Court rejected an attempt by Republican congressmen to overturn those lines. Those lines are expected to hold a GOP advantage in Wisconsin's congressional delegation.

Evers welcomed the high court's decision to keep the congressional maps in place, saying in a statement that it was "great news for the people of our state and our democracy, and it's been a long time coming."

But he called its rejection of the state maps a "remarkable departure" for the court.

"Our maps are far better than Republicans' gerrymandered maps we have now and their maps I vetoed last year, and we are confident our maps comply with federal and state law, including the Equal Protection Clause, the Voting Rights Act, and the least-changes standard articulated by the Wisconsin Supreme Court," Evers said. "If we have to go back to the Wisconsin Supreme Court—who have already called our maps 'superior to every other proposal'—to demonstrate again that these maps are better and fairer than the maps we have now, then that's exactly what we'll do. I will not stop fighting for better, fairer maps for the people of this state who shouldn't have to wait any longer than they already have to ensure their voices are heard."

The Supreme Court has, so far, shied away from ordering redraws of congressional maps that have already been passed. In their decisions, the court cited the upcoming primary election dates as reason to not drastically change congressional lines before the 2022 midterm elections.

In Alabama, the high court halted an ordered a lower federal court to redrawing the state's congressional map and struck down attempts by anti-gerrymandering advocates and Democrats who were hoping to add a second Black-majority congressional district in the state.

In Pennsylvania and North Carolina, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down Republican-led attempts to throw out the maps adopted by their respective state supreme courts. Both maps kept the political split of Democratic and Republican seats relatively equal and competitive.

But in their decisions this redistricting cycle, conservative-leaning U.S. Supreme Court justices left the door open for these maps to be changed after 2022, and for a debate on how much power state courts should have over the redistricting process.

In a written dissent to the court's decision in North Carolina, Justice Samuel Alito cites the U.S. Constitution's Elections Clause, which notes, the "Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof." Alito sides with the argument made by Republican challengers that state legislatures exclusively hold the that power of redistricting.

"If the language of the Elections Clause is taken seriously, there must be some limit on the authority of state courts to countermand actions taken by state legislatures when they are prescribing rules for the conduct of federal elections," he wrote in his dissent.

Republican leaders in North Carolina's legislature have filed another request to the U.S. Supreme Court to hear its argument on the Elections Clause.

Four states are still in the process of redrawing their congressional lines, while at least 21 states are currently in or have seen litigation over their passed congressional or state legislative lines, according to the Brennan Center.