Supreme Court grapples with fights over public officials blocking constituents on social media

Washington — The Supreme Court on Tuesday wrestled with a set of disputes over public officials who blocked critics on social media, attempting to tackle questions of how elected officials interact with their constituents online years after they were confronted with a similar court fight involving former President Donald Trump.

The cases, one from California and a second from Michigan, were the first of several the justices will weigh this term that test how the First Amendment's free speech protections apply in the age of social media. Other disputes that will be heard involve the constitutionality of laws in Texas and Florida that impose new regulations on content moderation policies, and a challenge to the Biden administration's efforts to address misinformation online.

The legal battles before the court Tuesday involve one current and one former member of the Poway Unified School District Board of Education in San Diego, California, and the city manager of Port Huron, Michigan. In both of the disputes, the public officials blocked followers who posted critical comments, and were then sued by those users for doing so.

In the California case, a federal appeals court sided with the blocked followers after examining the appearance and purpose of the accounts. The dispute in Michigan led to the opposite outcome, with a federal appeals court ruling in favor of the city manager after concluding in part that maintaining a social media account was not among his official duties. The key question in both court fights, though, is whether a public official is engaging in a government action when they block a follower on social media. If they are, then the First Amendment would apply.

Supreme Court oral arguments

Across more than three hours of arguments Tuesday, the justices at times expressed skepticism that any job-related discussions on a personal Facebook page means a government official is acting in his or her official capacity, and are therefore engaging in "state action" that is subject to First Amendment scrutiny when they block followers.

"One of the concerns I have about the line-drawing is to define doing your job as talking about your job is really quite all-encompassing really," Justice Brett Kavanaugh said, noting that many elected officials enjoy speaking to constituents about their work while they're not formally on duty.

He asked whether posts by public officials on their personal social media accounts about matters such as recycling pick-up, weather-related school closures or reminders to lock car doors to prevent burglaries would constitute state action if the information wasn't available elsewhere.

"That's the kind of practical information people are going to need," he said.

Other justices seemed to acknowledge how social media has changed the ways in which citizens and their elected officials interact, and seemed concerned about adopting rules that fail to account for the level of discourse taking place online.

"More and more of our government operates on social media, more and more of our democracy operates on social media," Justice Elena Kagan said. She warned that citizens could be prevented from participating in democracy if the court finds public officials are acting in their personal capacities and can therefore keep followers from interacting with them on personal social media pages.

Kagan continued: "It's a big picture challenge about the nature of the world we live in and we're going to live in and the need for rules that are going to meet a world that we don't really have any idea what it will look like."

But Chief Justice John Roberts warned of how public servants themselves could be impacted by a ruling that sets broad parameters for their duties or authorities.

"On these pages, people have both a job in the government and they have all sorts of other things, whether it's cats or children or whatever it is," he said. "We have to disaggregate that and say well, you have to have a governmental page and you have to have a private page and you can't mention the government on your private page or else it's going to become a government page."

Efforts to "disentangle" private from official capacities "doesn't really reflect the reality of how social media works," he said.

Though the cases involved local officials from California and Michigan, they invoked an issue that arose during Trump's presidency when he was sued by a group of Twitter users who were blocked from interacting with his account. A federal appeals court said Trump's move was unconstitutional, but the Supreme Court wiped away the decision and ordered the case dismissed after he left office.

Kagan raised Trump's use of social media during his presidency, noting that though his account on Twitter, now called X, was personal, he often used it to announce policy changes.

"I don't think a citizen would be able to really understand the Trump presidency, if you will, without any access to all the thing that the president said on that account," she said. "It was an important part of how he wielded his authority, and to cut a citizen off from that is to cut a citizen off from part of the way that government works."

The California case

The first case before the court Tuesday involved Michelle O'Connor-Ratcliff, the current vice president of the Poway Unified School District Board of Education, and T.J. Zane, a former board member. Both created public Facebook pages while they were running for positions on the school board in 2014. O'Connor-Ratcliff also had a public Twitter page.

Christopher and Kimberly Garnier, residents of San Diego County whose three children were enrolled in the school district, interacted with the board members' social media accounts frequently, often with "repetitious and non-responsive comments and replies" to their Facebook posts and tweets, according to court papers. In one instance, Christopher Garnier made the same comment on 42 different posts by O'Connor-Ratcliff, and issued the same reply to 226 of her tweets.

In response to the comments, O'Connor-Ratcliff and Zane blocked the Garniers from their social media accounts, which prompted the couple to sue. The Garniers argued the board members violated their First Amendment rights by blocking them on social media, which they claimed were public spaces.

A federal district court sided with the Garniers, concluding that O'Connor-Ratcliff and Zane blocking them amounted to state action. The board members, the court found, "swathed [their social media pages] in the trappings of [their] office" by listing their positions as board members, identifying themselves as government officials and listing a school district email address on the page, in O'Connor-Ratcliff's case.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit upheld the lower court's decision and concluded the Garniers' First Amendment rights were violated. O'Connor-Ratcliff and Zane "acted under color of state law by using their social media pages as public fora in carrying out their official duties" because "they clothed their pages in the authority of their offices and used their pages to communicate about their official duties."

"Both through appearance and content, the Trustees held their social media pages out to be official channels of communication with the public about the work of the PUSD Board," the three-judge 9th Circuit panel found.

O'Connor-Ratcliff and Zane appealed the decision to the Supreme Court and argued that an official's operation of a social media page does not constitute state action when no actual state duty or authority is involved. The case is known as O'Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier.

"If no law or policy requires maintaining a social-media page, officials' use of their own accounts to talk about their jobs is typically done 'in the ambit of their personal pursuits,'" their lawyers wrote.

The Michigan case

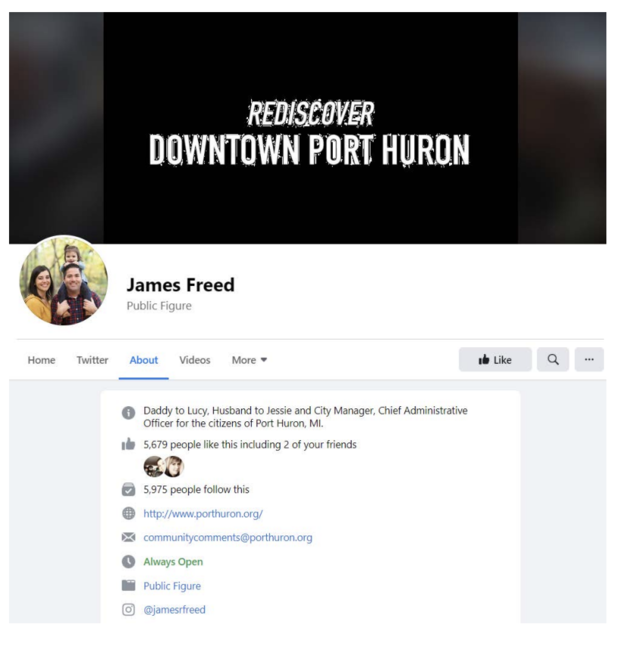

The second court fight arose from comments posted by Port Huron resident Kevin Lindke to city manager James Freed's Facebook page in March 2020 that were critical of the city's handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. The case is known as Lindke v. Freed.

Freed had a private Facebook profile that he converted to a public page after he was named city manager in 2014. The page identified him as a "public figure," and listed a Port Huron website and email address, as well as City Hall for the physical address associated with the page.

Freed wore a city manager's pin in the profile photo. He used the page to share information about city programs, his work as city manager and, in early 2020, updates about the pandemic. He also shared personal updates.

While Freed and Lindke engaged in some back-and-forth on the Facebook page about the city's COVID response, Freed deleted the constituent's comments and blocked each of the three Facebook profiles that Lindke was using to post responses.

Lindke then sued, alleging his First Amendment rights were violated when Freed deleted his comments and blocked his accounts.

A federal district court ruled in favor of Freed, finding that his Facebook activity was not state action and therefore shielded from First Amendment scrutiny. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit affirmed the lower court's decision and laid out a "duty-or-authority test," under which social media activity would be subject to constitutional scrutiny only if it is conducted in furtherance of governmental "duties" or where the activity depends on "state authority."

Freed, the court said, was acting in his personal capacity and had not engaged in state action. No law required him to operate a Facebook page as part of his duties, and he didn't rely on government resources, such as staff, to manage it. The profile also didn't belong to the city manager's office, the appeals court concluded.

Lindke asked the Supreme Court to review the decision, which he said ignores the role of a page's appearance and function. Freed, he argued, designed his Facebook page to appear as a government outlet and used it to perform public responsibilities.

The Biden administration backed the local officials in the cases.

A blurred line

The cases come to the court as officials across all levels of government have looked to social media as a primary means of communicating with their constituents and sharing information with the public. But "the line between official and personal social media pages is often blurry, especially when a candidate continues to use the same social media account before and after they are elected to office," said Kristi Nickodem, a professor at the University of North Carolina.

"It's challenging for courts dealing with these cases to draw lines that provide robust protection for free speech and access to information, while also clearly defining how public officials may adequately separate their official and personal actions on social media," she said.

These disputes, though, present the Supreme Court with an opportunity to resolve the split between the federal appeals courts over how to look at the issue of when a public official's activity on social media constitutes state action.

The justices could adopt a version of one of the tests applied by the appeals courts or develop a new one altogether, Nickodem said.

"Will the court adopt a test that focuses on whether a government official appears to be acting in his official capacity on his social media account? Or will the court apply an inquiry focused more on the extent to which social media communication was one of the public official's legally mandated or authorized duties?" she said. "State and local government officials are eager for clarity from the court on when and how the First Amendment constrains what they can or cannot do on their social media accounts."

Katie Fallow, senior counsel at the Knight First Amendment Institute, warned that if the Supreme Court takes a narrow view of state action, as the 6th Circuit has done in Lindke's case, many public officials will use personal social media accounts and argue they're not subject to the First Amendment, even if they appear to be closely tied to their professional roles and are sources of discussion with constituents.

"A ruling will have an impact on whether public officials can privatize their virtual town halls, and then they'll be able to block anyone they want and make it look like a one-way cheering section for the government," she said.

A decision from the Supreme Court is expected by the end of June.